Like politicians (see inset), WUR is also aiming for a future with as few animal trials as possible. As an ACT assignment, five students started looking for animal-free alternatives for the animal practicals in Wageningen’s education. ‘Being able to change direction requires you to look at it from a different perspective.’

Animal trials for educational purposes do not account for much in the total for Wageningen: about 1 per cent. However, every animal experiment where the learning objectives can also be achieved without using animals is one too many. Technological alternatives to animal trials have been growing fast in recent years. The students’ mission was to find out whether there are suitable alternatives to using animals and animal derivatives in Wageningen practicals, and if so, where and how.

Five students started investigating these questions as part of the Academic Consultancy Training (ACT) Master’s course. They delved into the literature and interviewed animal practical teachers and the former director of the lab animal facility Carus. Using the study guide, they assessed the extent of the practice. Zwaan Pijnenburg, Master’s student in Biology: ‘The number of official animal trials for educational purposes isn’t very high in Wageningen, but if you look more broadly and include practicals involving other animals or animal material, you’re soon talking about at least 40 to 60 courses.’

Teachers do not take the use of animals lightly, the students emphasize. Sabine Bastiaans, Nutrition and Health Master’s student: ‘Teachers consider very carefully how they can design their courses and practicals to minimize the impact on lab animals. Some teachers have switched to abattoir material, for example when teaching pig reproduction. Another teacher replaced fin clipping in zebrafish with a less invasive skin swab to collect DNA and learn how to do sequencing. And there are many more examples like this.’

Four students, one chicken

Nowadays, alternatives for animal trials are likely to involve hi-tech solutions, such as 3D bioprinting, an organ-on-a-chip or digital twins. Not much benefit can be expected from this in the short term as regards teaching practicals, the ACT students think, because these solutions are still too expensive and complex. But WUR could teach students more about them. Pijnenburg: ‘Understanding how you can apply that technology, what data and models tell you about the “real” animal, is important knowledge for the new generation that will need to create a future without lab animals.’

They emphasize that a lot can be gained with relatively simple approaches. Pijnenburg: ‘For example, let the teacher demonstrate the “real” dissection, while the students follow that process using a plastinate. These come in all shapes and sizes. In some, you can even take something out or put something in, just like with a real animal. It’s very suitable for many learning purposes.’

Or have multiple students work on one animal, Bastiaans suggests. ‘In Ghent, where I studied veterinary science for two years, for dissections we had four students working on the same chicken – that was fine. WUR has quite a lot of animal practicals with piglets*, where one piglet is often used for every two students. Make that one for every four students and you’ve already halved the number of animals you need,’ she suggests.

Video

While the teachers interviewed might view the switch to alternatives positively, they don’t yet consider it feasible to end the use of animals entirely, Bastiaans says. ‘They say that it would make education less effective or less interesting.’ The students themselves are more optimistic about the feasibility of animal-free education. Bastiaans: ‘The current setups of many practicals were developed over the years. To be able to change direction, you have to look at it from a different perspective. Take the learning objective as the starting point: how can we achieve it without needing animals?’

They believe you don’t always need to enter the lab for the learning objectives in question. Sometimes a video clip is enough. ‘Teachers are reluctant to use videos because after Covid they got a reputation for being boring. But that was during lockdowns when everyone was at home staring at a screen all day. If you show a video in the lecture room and link a fun knowledge quiz to it, everyone is sure to pay attention,’ Pijnenburg thinks. Another good idea, according to Bastiaans, is to let students make a video themselves. ‘For the Molecular Regulation of Health and Disease course, I once had to make a stop-motion video about an enzyme pathway in the liver. Beforehand, I wondered what that was going to teach me, but I’ve never learned to understand something as well and as quickly as I did then.’

* These are stillborn piglets that WUR obtains from a pig farmer; they are not killed for the practicals (and are therefore not legally lab animals).

The ACT assignment was done by Sabine Bastiaans (Nutrition and Health), Ruth Maguinness (Animal Science), Nathalie Mendez (Nutrition and Health), Zwaan Pijnenburg (Biology) and Ilse Schleijpen (Animal Science). Their client: Ali Youssef, a lecturer in the Adaptation Physiology group who pioneers a lot of new technologies, such as sensors and digital twins, that could eventually make some animal trials unnecessary.

About animal trials and lab animals

The Experiments on Animals Act regulates research with vertebrate animals (except some primates; experiments with the apes* are prohibited) and squid and octopuses. Trials with insects are legally not animal trials. Animal experiments are defined as when the research involves some degree of harm to the animal. Research on tissues or organs from animals that are specifically killed for the purpose also counts as an animal experiment. The same research with material from animals that die from different causes, such as slaughter, is legally not an animal trial.

*Chimpanzees, bonobos, orang-utans and gorillas.

Politicians want fewer trials with lab animals

The Dutch Parliament wants the Netherlands to be a leader in reducing animal trials and developing alternatives that do not require lab animals. Almost all parties supported a motion to this effect by the Party for the Animals last week. For some years, WUR has been investigating solutions for a future where lab animals are not needed; it is one of the pillars of the prestigious Next Level Animal Sciences research programme.

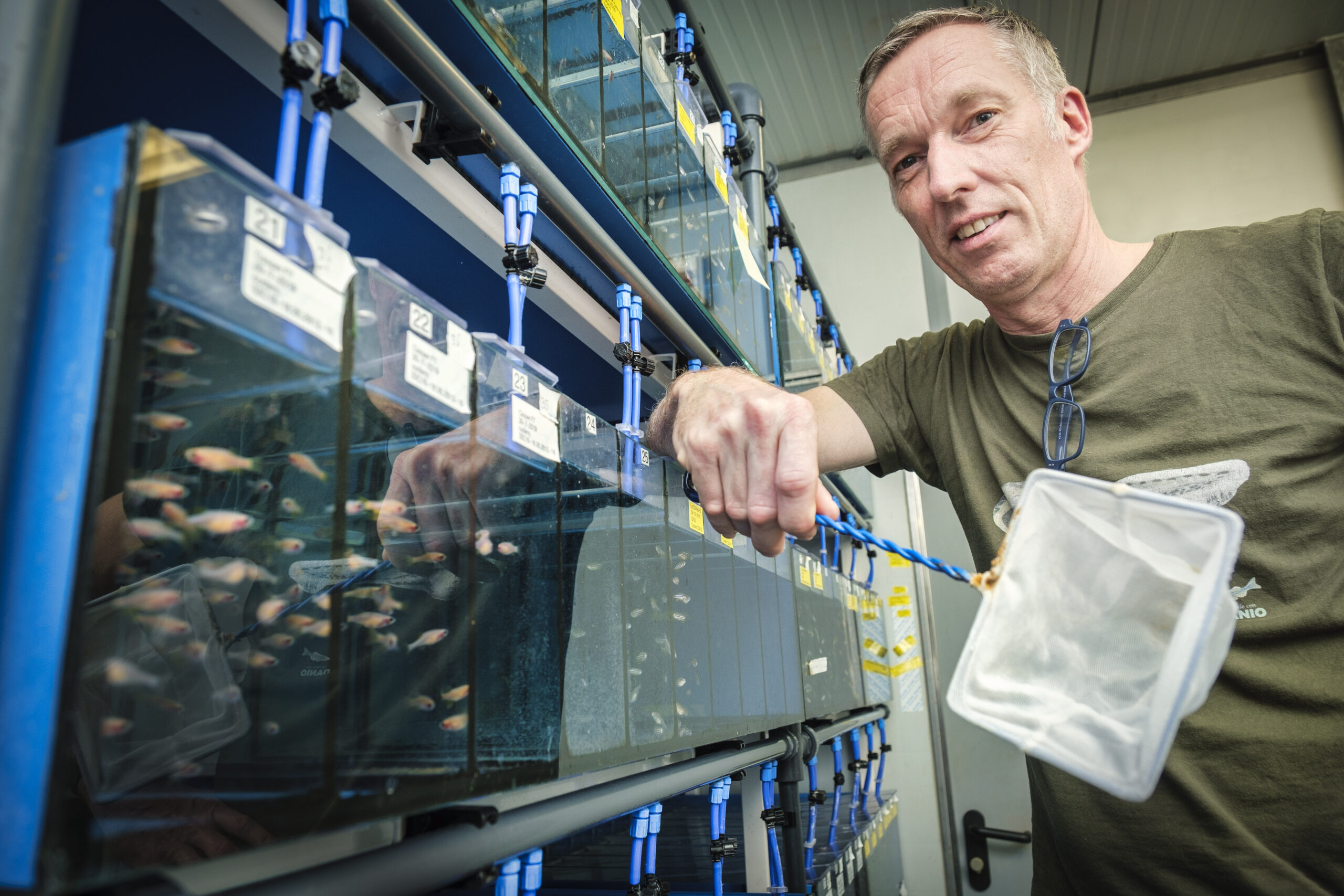

The most recent figures on animal trials at Wageningen are for 2023; the annual report for 2024 has not yet been published. In 2023, WUR did 56,363 tests on animals, 20 per cent less than the previous year. The majority (73 per cent) were trials with fish, with the goal of monitoring stocks and studying migration. The lab animal dossier at WUR.nl has more figures and background information about animal trials and laboratory animals.

Plastinate of a piglet’s head. Photo Utrecht University

Plastinate of a piglet’s head. Photo Utrecht University