More and more catfish are being spotted in the Netherlands, at more and more locations. And there are more and more XXL specimens among them. The question is whether that is good news, ecologically, and particularly with migrating fish in mind. A field study involving tagged catfish aims at clarification on this point.

‘Fishing for catfish can be just like gaming,’ says Master’s student Max de Koning (Aquaculture & Marine Resource Management), pointing to the LiveScope, a gadget that reveals what is going on underwater using sonar. On board with angler Paul Swinkels, you see what he means. The brightly coloured figures on the screen hold your attention and it gets very exciting when one of them approaches the place where De Koning and Swinkels’ bait is hanging in the water.

The angler and the student are fishing with a scientific aim in mind. Because although the European catfish (Siluris glanis) is being spotted in Dutch waters more and more frequently and in increasingly impressive sizes, questions remain about the predator. For a start, we don’t know exactly what its diet consists of. All sorts of anecdotes circulate among anglers – catfish are said to regularly gobble up waterbirds and rats, for instance – but these might just be tall stories. Nor do we know exactly how and where catfish go hunting. Wageningen Marine Research (WMR) is now doing research into both questions at the behest of the ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management (Rijkswaterstaat) and the ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries, Food Security and Nature.

All you can eat There are indications that catfish feast en masse on migrating fish that are held up at locks, weirs and other obstacles. There are also reports that they eat a lot of American crayfish and Ponto-Caspian gobies, two invasive exotic species. That would be good news for the indigenous ecology, but the massacre of migrating fish would not.

It is still not clear what the catfish really eats

‘Many indigenous migrating fish species are not thriving,’ says project leader Jacco van Rijssel. ‘Various measures are being tried to increase their numbers, including release programmes and additional fish passages. Before you do that, you want to know whether the migrating fish constitute a sort of “all-you-can-eat buffet” for the catfish.’

Van Rijssel hopes to tag 30 catfish for this study. That is being done on the River Maas, near the hydroelectric plant at Lith, both up- and downstream. Some of the catfish are part of the bycatch of professional fishers. But amateur anglers who Marine Research works with play a big role too. They have already spent many evenings out on the Maas, because catching a catfish is no child’s play.

Not small fry

And that’s clear on board Swinkels’ boat. He and De Koning cast their rods out near a gulley in the riverbed and let the boat float with the current. For a while, not much happens. Now and then a patch of colour appears on the screen and De Koning can feel through his rod that a fish is investigating the bait – but they don’t really bite. Meanwhile, dusk is falling, and that is ‘the time of day when the catfish is most active’, Van Rijssel has told us. And to be sure: on the screen appears a large red and yellow figure that swims lazily towards the spot where Swinkels’ bait is hanging in the water. The patch lingers there a moment and then swerves away, only to turn back quick as a flash. ‘Hang!’ roars Swinkels as he jerks his rod up. Yes, a catch – and not a small one. The rod bends deeply under the weight of it, the reel slips and Swinkels nearly busts a gut reeling in the fish: this is no small fry.

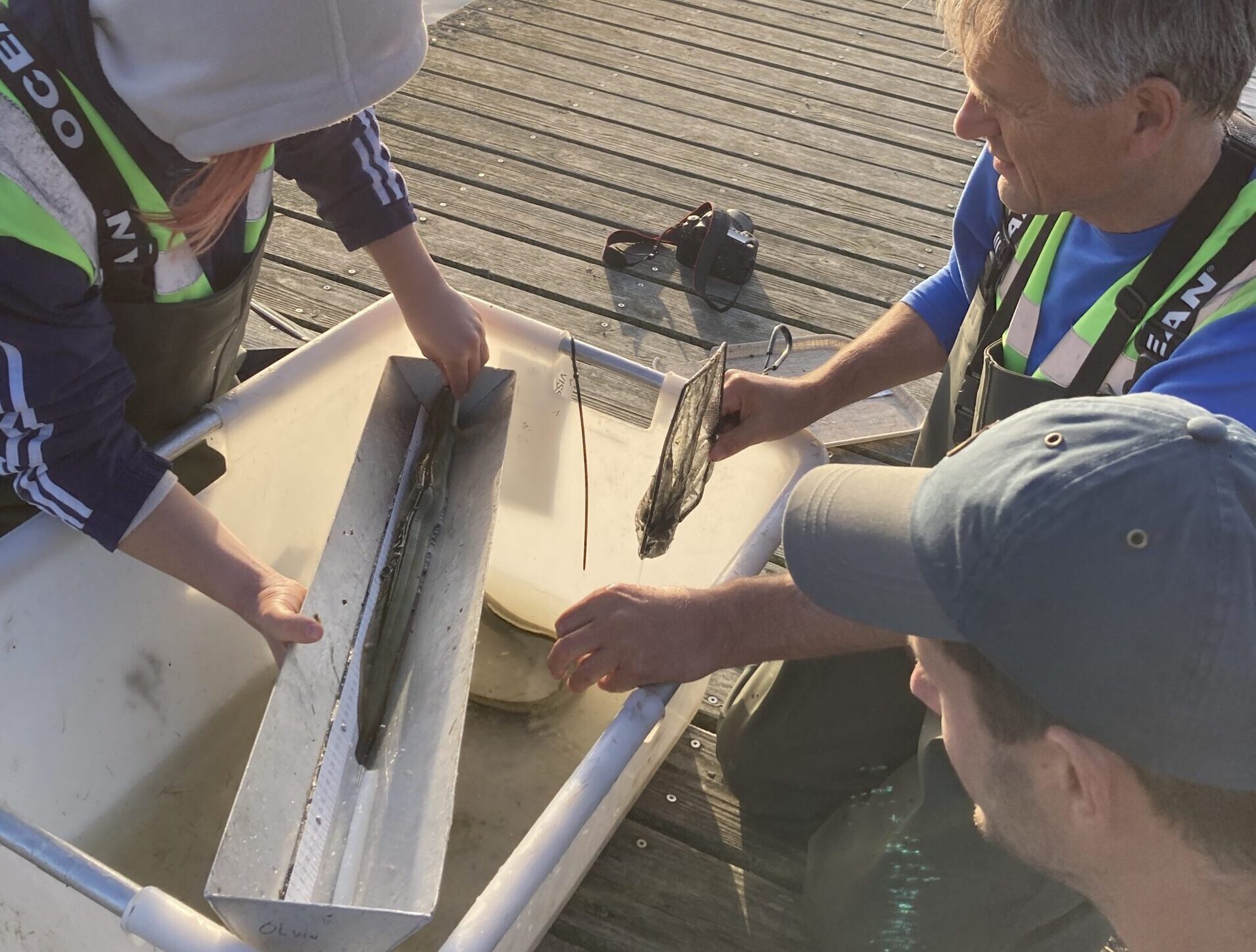

A little later, Swinkels’ boat is speeding over the Maas to rush the freshly caught catfish to Van Rijssel, who has his research equipment at the ready next to the hydroelectric plant. The fish is carefully hoisted up on a kind of stretcher and laid in a basin full of 2-phenoxyethanol to anaesthetize it. After a few minutes, once the fish is sufficiently sedated, the research ritual can begin.

Grazes

The researchers try to retrieve the contents of the fish’s stomach using a water jet and a sieve. If the fish is large, the researchers sometimes extract the leftovers by hand – wearing a sturdy glove as the sandpaper-like tissues of a catfish’s mouth can cause severe grazes. Today, De Koning only finds an otolith-like object (a ‘stone’ from the inner ear of fish); previously the researchers found the remains of a wild duck. Then they weigh and measure the catfish, De Koning takes a DNA sample by clipping tissue from a fin, and the fish is fitted with a tag just below the skin. ‘At the fish passage next to the weir there are two antennae that can read this tag, so we can see which direction it’s swimming in,’ explains Van Rijssel.

Big enough catfish – and at 120 and 137 centimetres, both Swinkel’s catches this evening qualify – are also fitted with an acoustic transmitter the size of an AA battery. It is placed in their abdomen and will work for about 10 years. The transmitter is used for fish of over 80 centimetres. Van Rijssel: ‘Salmon and silver eels that pass here on their way to their spawning grounds can be 60 to 100 centimetres long. To be capable of devouring such large prey, a catfish needs to be substantially bigger.’

Once the incision in the abdomen has been neatly stitched – Van Rijssel is qualified to do this – the fish goes into a tank with flowing Maas water to recover. That doesn’t usually take long, says Van Rijssel, who almost immediately feels two jaws clamping down on his thumb. ‘Ow! Well, this one is well on the way to recovery: its biting reflex is back,’ he grins. It is nearly midnight before the work with the catfish – now legally classified as lab animals – is done. They are carefully returned to where they were caught: upstream or downstream. And now let’s hope they reach a good old age, so they generate lots of data that help solve the mysteries of the catfish.

Record-breaking catfish

On the River Waal near Nijmegen a catfish was caught recently that was 2.54 metres long: a new record for the Benelux region. In an earlier number, Resource interviewed Sophie Nietzel of Wageningen Marine Research, who is involved in this project too, about record catfish catches. In angling circles she is known as one of the best catfish anglers in the Netherlands.

Project leader Jacco van Rijssel (left) and Aquaculture & Marine Resource Management Master’s student Max de Koning use a jet of water and a sieve to retrieve the stomach contents of the sedated fish. Photo’s Marieke Enter

Project leader Jacco van Rijssel (left) and Aquaculture & Marine Resource Management Master’s student Max de Koning use a jet of water and a sieve to retrieve the stomach contents of the sedated fish. Photo’s Marieke Enter