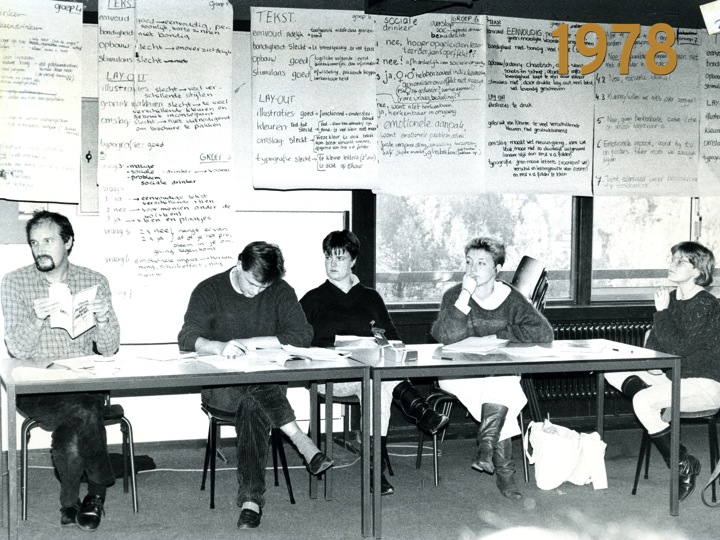

Last week, the Leeuwenborch’s 50th anniversary was celebrated in style with a seventies-themed event. Fifty years is more than half a lifetime. Resource travels back in time with two Lebo residents who were there from the start (or almost): Cees van Woerkum (emeritus professor of Strategic Communications and former director of Social Sciences) and Anton Schuurman (researcher in Economic and Environmental History). ‘My work and the people at Leeuwenborch have taken me to places I would never have been to otherwise.’

It was autumn 1974. While most Dutch people were still getting over the calamity of losing the World Cup final and the associated ‘pool party affair’ (millennials and Gen Z: google it), Wageningen had something positive to look forward to: Leeuwenborch was about to open. The building was designed by W.R. de Vries and has a modernist appearance. Its purpose was equally forward-looking: to be the single location housing all the social science groups at Wageningen.

Valhalla

Having everything in one place was a new concept at the time, says Van Woerkum, who worked at Leeuwenborch from when it opened in 1974 until he retired some five years ago. ‘At the time, the other science groups at Wageningen were spread around the town. To have all that social science expertise concentrated in one physical location was really unusual.’

That was also the case for the large shared library, recalls Schuurman, who has worked at Leeuwenborch continuously since 1978. ‘That library later became part of the big WUR library. But back then it was a real Valhalla, somewhere you could browse all the sociology and economics journals in one place.’

The shared premises didn’t necessarily mean the various groups were constantly in contact with one another, though. ‘I have always said we should work together more at Leeuwenborch to find an answer to how to tackle the challenges facing WUR. Certainly in the early days, it was all still a collection of self-contained islands,’ says Van Woerkum.

Each island had its own habits and customs, and even dressed in a distinctive style. Schuurman laughs: ‘The Law group always looked very neat and tidy in suits, like at nearly all universities. Then there were the economists, who were also relatively smart. And finally the sociologists, with their tank tops and corduroy trousers.’ He also remembers the Lebo students having their own ‘dress code’. ‘How should I put it? Typically Wageningen; you didn’t find any chic city girls here.’

Form and function

Leeuwenborch got its name from an old district in the vicinity. Both the Lebo veterans liked the building as a place to work. Van Woerkum: ‘It was light and spacious and had a huge canteen. The only disadvantage I found was that it didn’t have a central staircase that could take you from the ground floor right to the top. There was one big staircase to the first floor, but to get to the next few floors you had to go to the end of the corridors and use these narrow, unpleasant cement staircases. That wasn’t so great.’

Schuurman on the other hand liked the unusual layout for the staircases. ‘The best way to get to the higher floors was by lift, so the lift became a kind of enforced meeting point. The only people who took the stairs were the ones who worked on the first floor; the rest took the lift. That meant you bumped into people automatically. Especially because back then, unlike now, nearly everyone went to lunch at the same time at twelve thirty. So the weird staircase set-up gave the lift an important social function.’

Too relaxed

Both Schuurman and Van Woerkum say that incredibly sociable atmosphere declined over time. ‘When the weather was good, the whole group would go and sit outside on the grass. But eventually they stopped doing that,’ says the emeritus professor. ‘It all became a bit more business-like. To some extent I don’t think that was a bad thing because the atmosphere could be a little too relaxed in the seventies. There were colleagues who didn’t lift a finger as far as I could tell.’

However, the pressure to perform (and publish articles) has now gone too far in his opinion. ‘And that has been at the expense of contact with practitioners, which I always found very important. It hasn’t been good for the academics’ feeling for what goes on in practice. But I can’t deny that the academic achievements have improved distinctly, both in quantity and in quality.’

Working from home

In contrast to the first few years after retiring, Van Woerkum only comes to the Lebo very occasionally these days, even though he lives a stone’s throw from the building. ‘In the past you would always find me here. Except for one day a week, which I spent at home writing articles. No one was allowed to disturb me then, not even the secretaries. Otherwise I’d never publish anything, because I found it impossible to write anything at Leeuwenborch. We had a very lively, hectic group, with a steady stream of students, PhD candidates and visitors who wanted to share knowledge. So that one day a week at home was sacred.’

Van Woerkum was a pioneer in working from home. ‘That wasn’t done back then. You spent all your working hours in your office at your desk, which consequently played an important role in your life,’ explains Schuurman. He would even regularly come to Leeuwenborch to work at night. ‘You didn’t have PCs in those days; we worked on a mainframe. But the whole university used it so you’d often find when you arrived at work at eight thirty in the morning that it was already so overloaded you couldn’t even log on. The only way I could work uninterrupted on large datasets was to start at ten o’clock in the evening and work through the night. That’s also why I had my own key to the building. We didn’t think that was odd at all; there were other colleagues too who did the same.’

Van Woerkum also well remembers the early days of IT. ‘The first computer I had was a Bondwell and I remember it had this awful font — those green letters on a black screen. And I had one of those dot matrix printers — I must have some of that grey output lying around somewhere. But it was a huge advance. As a group, we were quite early adopters. “Our” Joke Jansen [who is also Van Woerkum’s partner, ed.] was the first in Leeuwenborch to automate the student administration. That was a major improvement on all those card index boxes.’

A window on the world

Schuurman says it’s not just because of the huge amount of time he has spent in Leeuwenborch that he feels a special connection with the building. ‘I came here in 1978 after studying History in Nijmegen — which meant Dutch history. It was a real transition to come to Leeuwenborch, which had an incredibly international outlook back then. Wageningen as a whole was very much oriented towards the tropics anyway, and the Lebo groups naturally thought in terms of the Western/non-Western divide. The first-year students I taught also got courses in “world history”, for instance. That international perspective is the norm now, but in my early years at the Lebo it broadened my view of the world considerably.’

That international outlook also had a big impact on Van Woerkum, he says. ‘For example, I had a PhD candidate from China. Later on, I visited him in Beijing because we’d become quite friendly. That was really nice. Then there were the international conferences and working visits. My work and the people at Leeuwenborch have taken me to places I would never have been to otherwise.’

Colour photos by Guy Ackermans; black-and-white photos from the Strategic Communications archive.

Colour photos by Guy Ackermans; black-and-white photos from the Strategic Communications archive.