Wageningen biochemists Joris Sprakel and Dolf Weijers have been awarded a Gravitation Programme grant of 22.8 million euros. They head a consortium of seven universities that will spend the next ten years studying plants’ sense of touch.

Biologists have known for about a century that plants ‘feel’ something when touched. Take carnivorous plants where the leaves snap shut as soon as they sense prey. But it is still not clear how this functions at the cellular level, without the aid of brains or nerves. Now researchers from Wageningen, Utrecht, Nijmegen, Eindhoven, Groningen, Amsterdam (VU) and Leiden will be working together on this in the new ‘Green Tissue Engineering’ project.

Language of cells

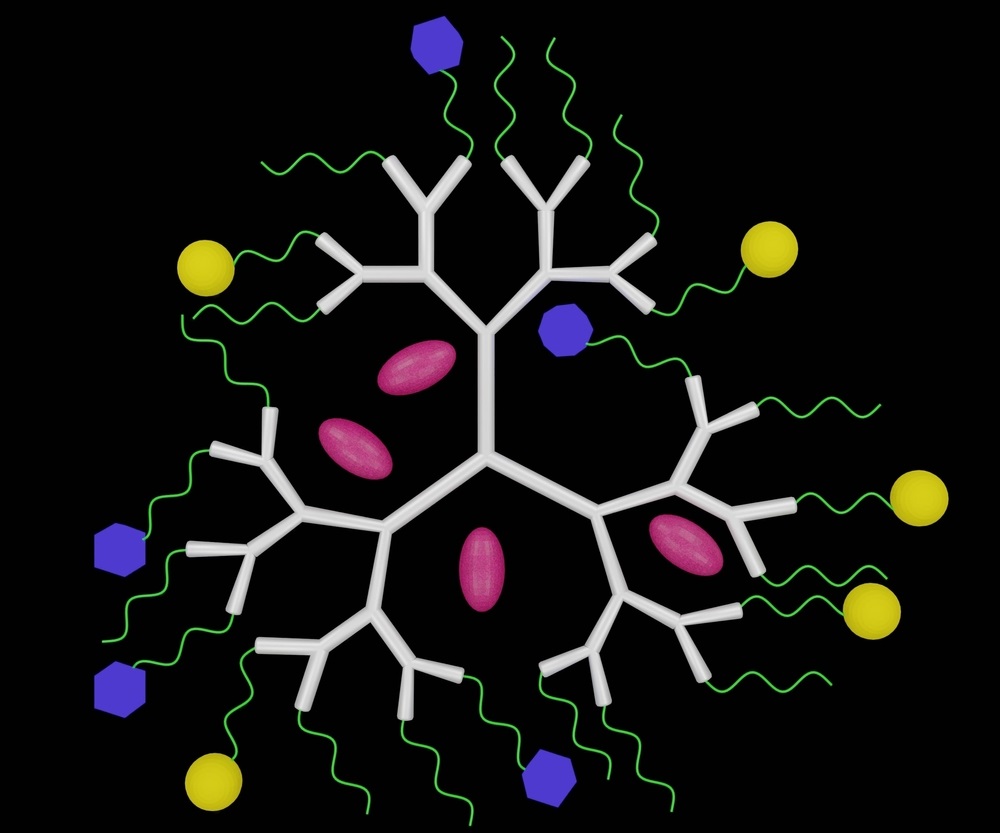

The project requires an interdisciplinary approach. ‘When cells talk to one another, they do so using the language of cells, which is biochemistry,’ says Weijers. But contact, wind or a fungus that penetrates the plant are all mechanical stimuli. ‘The plant has to translate the mechanical signals into the language of cells.’ The researchers want to use this fundamental knowledge, for example to make plants more resistant to disease. ‘To infect a plant, pathogens have to get through the plant’s tough outer layer,’ explains Sprakel. That means there is mechanical contact between the two. ‘If we know how the plant activates its defence systems, perhaps we can make it particularly sensitive to such signals,’ says Weijers.

Touch is a mechanical signal that the plant has to translate into the language of cells

Within the project, 57 young scientists will be able to work on subprojects. ‘The training for PhD candidates often involves a strong focus on a single discipline,’ says Sprakel. But this project gives us the opportunity to train people in biology, physics and chemistry.’

Plants can ‘sense’ touch. This is how carnivorous plants know when prey is on their leaves. Photo Shutterstock

Plants can ‘sense’ touch. This is how carnivorous plants know when prey is on their leaves. Photo Shutterstock