‘The country is opening up again,’ declared Dutch Health minister Ernst Kuipers in February 2022, and so it was. After two years of lockdowns, curfews, working from home, self-testing and social distancing, the world started to get back to business as usual. Now, Covid seems like a thing of the past, but that is not the case for everyone. Some people are still wrestling with the effects of Long Covid. Three WUR folk share their stories.

‘I’ve accepted that my life will never be the same again’

Rogier Schulte (49), full professor, Farm Systems Ecology Group

‘I can still vividly remember lying in bed and feeling as though my head was on fire. I could feel the physiological short-circuit in my head. I knew then that something was very wrong.

Things went wrong in March 2022. It started out as a mild cold, but the symptoms weren’t gone several weeks later. At first, I scaled down my work to half days but it soon became obvious that I had to go right down to zero: I turned out to have Post-Covid Syndrome.

Someone with boundless energy: that’s how I would have described my former personality. My mantra was that there is always a solution, if only you put enough time and energy into the matter in question. I led my chair group with inspiration and enthusiasm. I was a bit chaotic too: my thoughts and ideas often raced ahead to the next task. Suddenly I had to break my life down into the tiniest chunks. Everything I did, who I was, and even what I ate and drank. When I was allowed to start working again, I did so in blocks of 20 minutes max. After each task I took a 20-minute break, and then worked on something different for 20 minutes, followed by another break. It took a lot of puzzling to find out how these blocks of time fit together, and which activities could follow each other. I got help from an ergo-therapist; I could not have worked this out on my own. By keeping a diary, we figured out what worked for me.

I’ve been working fulltime again since September this year. I can cope with two 90-minute meetings a day, and two 90-minute periods of concentrated computer work. I still need to take breaks in between. That means I have to plan everything in a very disciplined way – quite unlike my old, more spontaneous self.

By now, I have accepted that my life will never be the same again. I’m trying to find a new way of life that is meaningful and enjoyable. Post-Covid Syndrome has taken all the spontaneity out of my life. I miss being able to say ‘yes’ to a suggestion to go out this evening. For the first time in 18 months, I do now have the headspace to plan a social activity every week. It’s so nice to do something that isn’t work-related.

I get frustrated by how little recognition there is for Post-Covid Syndrome in the Netherlands. That frustration is shared by my fellow sufferers. We do have a patients’ organization, but everyone struggles with dosing their energy. So it’s ironic: the last thing we’ve got the energy for is setting up an organization and actively contributing to it.

I started having hyperbaric oxygen therapy at the end of October. Israeli research shows that this therapy has a positive effect on the cognitive variant of Post-Covid Syndrome – in the short term, at least. There is a chance that this therapy will heal my invisible handicap and that I will no longer need to think about planning all day. That will make it all a lot more enjoyable.’

‘Last week I made a date with my best friends for the first time in a year and a half’

Carla Oonk (56), education coordinator, teacher and researcher at Education and Learning Sciences

‘In June 2022, we had just started teaching on campus again when I got Covid. I tested positive three days after my first seminar, so I went into quarantine. One day later, my head seemed to shut down. My vision was blurred and I was dizzy and nauseous. My head felt heavy, as if a tight band was squeezing it. My heart rate went through the roof and I had inflammation everywhere. My whole body was messed up.

I’m super-healthy normally. I can’t have had more than three days off sick in the 20 years I’ve been working at WUR. So I thought: I’ll just report sick and I’ll be back at work within two weeks. That’s not how it went.

I enjoy my job and I did my best to go on working. The company doctor wrote to my line manager saying: this woman wants to do too much. Not to push myself too hard, I started working from home, with strict limits: half an hour of work, then a walk, and then a lie-down. At my lowest point I worked for just an hour a day.

My social life was at a standstill, it took too much energy. And I didn’t celebrate Christmas with the family. At home I’m lucky: my husband and my sons are quiet and understanding. It must be awful if you’ve got young children, or live alone. Last week I made a date with my best friends for the first time in a year and a half, and that was a milestone.

By March 2023 I was able to work four hours a day. Around that time an article needed writing about Boundary Crossing, a project I’ve worked on a lot. A nice test to see whether I could cope with something like that. I noticed that it was too much for me, really, but I was determined to get it done. In May I totally crashed, which happens quite often with Long Covid if you come under too much pressure too soon. I was back to square one, and I struggled with unbelievable tiredness that I’d never experienced before.

In consultation with the company doctor, I decided to build up slowly again. In the summer I went cycling in England with my husband, and that did me good. Then I started building up, adding half an hour every two weeks. Now I’m working four hours a day, so there’s progress.

Difficult as it has been, I didn’t fall into a pit of despair. I kept in touch with my colleagues by email and stayed in the loop, thanks to their fantastic support, and that of my line manager, the company doctor and the ‘gatekeeper’ monitoring my sick leave. But Long Covid did test my patience. It is an uncertain business: some people are still not out of the woods after three years. The heaviest blow was after my relapse, when my line manager told me he was going to look for someone to take over my coordination tasks. Rationally, of course I could see that was necessary, but I had hoped I could prevent it by recovering as fast as possible. At the same time, it’s all relative: when I got Long Covid, I heard that a colleague of mine had breast cancer. Something like that puts my situation in a different light.’

‘Sometimes everything hurts and I think: maybe it won’t get better than this’

Julia Teresa Celis Moreno (34), PhD candidate in Cell Biology and Immunology

‘At the beginning of 2020, I had just finished the first year of my PhD. At that time, Covid was only a problem in Asia, or so we thought. One day I suddenly fell ill, with flu-like symptoms and stomach issues, and my whole body was not okay. I couldn’t make an appointment with a GP because I had just moved. A couple of weeks later I ended up going to the Student Medical Centre. The doctor said that I had a severe respiratory infection and sent me to the hospital, where I was given antibiotics.

Looking back, I had all the classic Covid symptoms: I couldn’t smell or taste anything, I coughed constantly and had trouble breathing. In the meantime I had a GP and I called him regularly. He prescribed painkillers and cough syrup, but I didn’t get better.

During the summer, the doctor finally referred me to a pulmonologist. But because I didn’t have an acute Covid infection, they didn’t treat me for that. I was still coughing and short of breath, and I had brain fog. This continued until December. Then I called in sick again and decided to visit my family in Peru.

I was admitted to hospital in Lima as soon as I arrived there, and was immediately given extra oxygen and medication. After a week in hospital, I stayed with my in-laws in Lima for another month, because I had to go to the hospital for regular check-ups. The rest of the time I mostly slept.

I came back to the Netherlands in March and at last, I received treatment here through a Post-Covid programme in which you are then treated by various specialists, such as a physiotherapist, a logopaedist and an ergotherapist.

My GP apologized to me. Now that he had seen all the test results from the hospital in Peru, and had seen other patients with similar complaints, he had realized that he could have done more for me. That did me a lot of good. The year before, he had advised me to see a psychologist because he thought it was all in the mind.

Things are going much better now. I started by working for two hours a week and now I am back at 32 hours. When I think of how I was and how things are going now, I am really happy. But sometimes everything hurts and I think: maybe it won’t get any better than this. That is extremely frustrating.

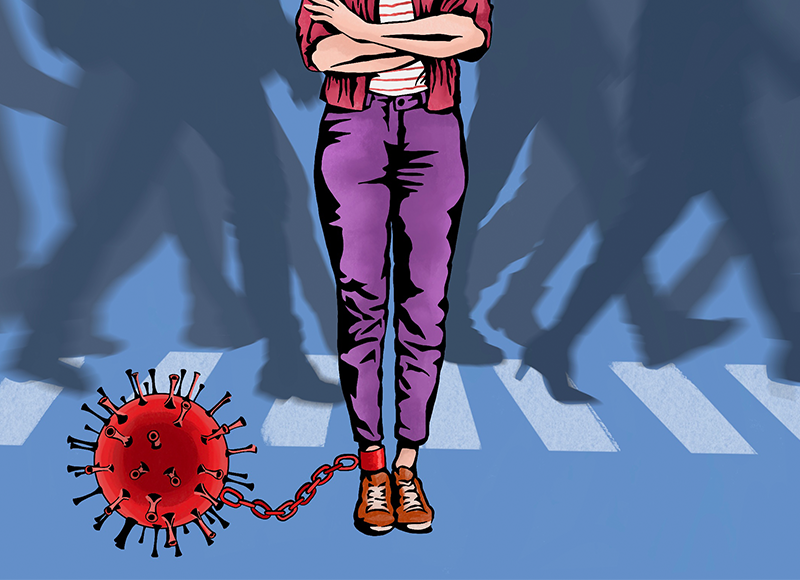

My supervisor has always been very supportive and the company doctor has also helped me a lot. The most difficult thing at the moment is the financing of my PhD. I should have finished a long time ago. When I asked the department for a contract extension, I was told that there was not enough money for it. Eventually I was given an extra six months through the Covid relief fund, but that is not enough. My supervisor and I are now looking at other options for grants to enable me to complete my PhD. It’s easier to have a broken leg — then everyone can see that something is wrong. If you have Post-Covid, your complaints are a lot less visible.’

Post covid (long covid)

Some of those who get COVID-19 suffer symptoms for a long time. If their symptoms go on for more than three months, they are considered to have Post-Covid Syndrome (also known as Long Covid). Common complaints among Post-Covid sufferers are fatigue, concentration problems, memory problems, breathlessness, oversensitivity to stimuli, headaches, insomnia and muscle pain. The nature and intensity of the symptoms vary from one person to the next.

It is estimated that 1.3 million Dutch people have developed Post-Covid Syndrome. Many of them had relatively mild symptoms and have recovered, but there are also people whose symptoms are so serious and long-lasting that it is hampering their participation in society. How big that group is in the Netherlands is not known. The government’s Social Impact Team estimates that there are about 90,000 people in this category.

Text Luuk Zegers, Coretta Jongeling and Dominique Vrouwenvelder. llustration Valerie Geelen

Text Luuk Zegers, Coretta Jongeling and Dominique Vrouwenvelder. llustration Valerie Geelen