Recruitment for the new Bachelor’s degree in Marine Sciences has topped all expectations. The first cohort of students started this September. Resource dived in and joined them on an excursion to Burgers’ Zoo.

At least 100 students are seated in the lecture theatre at the Safari Meetings Centre in Burgers’ Zoo in Arnhem. You would never guess from the eagerness with which they question Max Janse, the curator of Burgers’ Ocean, that most of them were out on the town last night. ‘Does the aquarium follow the lunar cycle?’ ‘How do you prevent the sharks from eating all the fish?’ ‘Where do you get live rock from?’ ‘What happens if parasites get into the aquarium?’

Janse has just given a lecture on the management of closed ecosystems such as the coral reef aquarium. ‘In a natural coral reef you find up to 1000 species of fish,’ he says. ‘In our coral reef we have about 50. Each species has a function. If the algae grow too fast, we release doctor fish. Terrific grazers, only you don’t want too many of them because then they start killing each other.’ He gives a second example: ‘When the glass anemone took over the coral, we put butterflyfish to work. But besides eating the anemone, they also ate the coral, which is exactly what we don’t want. It took four months to catch them again. So we’re always looking for a balance.’

It takes quite a bit of creativity to develop a tropical coral reef in Arnhem. And what about simulating tides, currents and moonlight? ‘Or the chemical composition of the water,’ adds Janse. ‘Which substances does it contain and in what concentrations? That’s one of the biggest challenges for me, because I’m a biologist, not a chemist.’

When Burgers’ Ocean opened in the year 2000, Janse and his colleagues looked to nature for solutions. ‘We thought: once we understand how it works there, we can apply that here.’ But that approach doesn’t work these days. ‘Nature is not doing well enough for that. Waters are warming up and coral is bleaching. If we were to simulate today’s natural conditions, our coral reef would be half-dead.’ He pauses and glances around the room. ‘That’s why we need your help: to study the complex problems in the field of marine sciences and come up with solutions to them.’

Holistic

And that is exactly why the new Bachelor’s degree has been launched, say course coordinators Rosa van der Ven and Celine van Bijsterveldt. Van der Ven coordinates the Introduction to Marine Science course and has been involved in developing the new degree programme for years. Van Bijsterveldt coordinates Marine Ecology and teaches several courses. ‘Problems in the marine domain are too complex to be solved using a single discipline,’ says Van der Ven. ‘They call for a holistic, interdisciplinary approach.’

She gives the example of a case that students are working on in this period. ‘The coral around islands is in decline. Looking at it purely as a marine biologist you’d say: put in artificial reefs so that you give the coral the chance to grow back. But it’s not that simple, because new reef attracts a lot of fish, so fishers think that’s where they need to be. The result is overfishing. We teach students to look at the bigger picture from day one.

I saw it as a sign that this degree would be run for the first time this year

Why did the reef deteriorate? How can we work with all the stakeholders to ensure that the reef recovers? By ensuring, for instance, that besides coral restoration, you work with fishers to explore the options for sustainable future-proof fisheries.’

The popularity of the new degree programme means the teachers need some improvisation skills, says Van Bijsterveldt. ‘We knew last year that there was a lot of interest, but in the first week of this academic year we realized we had more students than we had expected. So we had to adjust the timetable and we are having to do quite a lot of fine-tuning as we go along.’ But although it’s hectic, it’s enjoyable too, she says. ‘Especially when I can see that students make the right connections and ask good questions. I see that during excursions especially, because then they get input from outside, which brings the lecture material to life.’

Shark tank

After Janse’s lecture, guides show the students around in groups. Burgers’ Zoo guide Peter takes his group through the dark aquarium and points out various species of fish and corals. ‘There’s a sea urchin,’ he says. ‘Can they swim?’ asks a student. ‘No, but they do have a kind of sucker on their underside with which they can propel themselves along,’ the guide answers. ‘And over there are some pipefish, members of the seahorse family.’

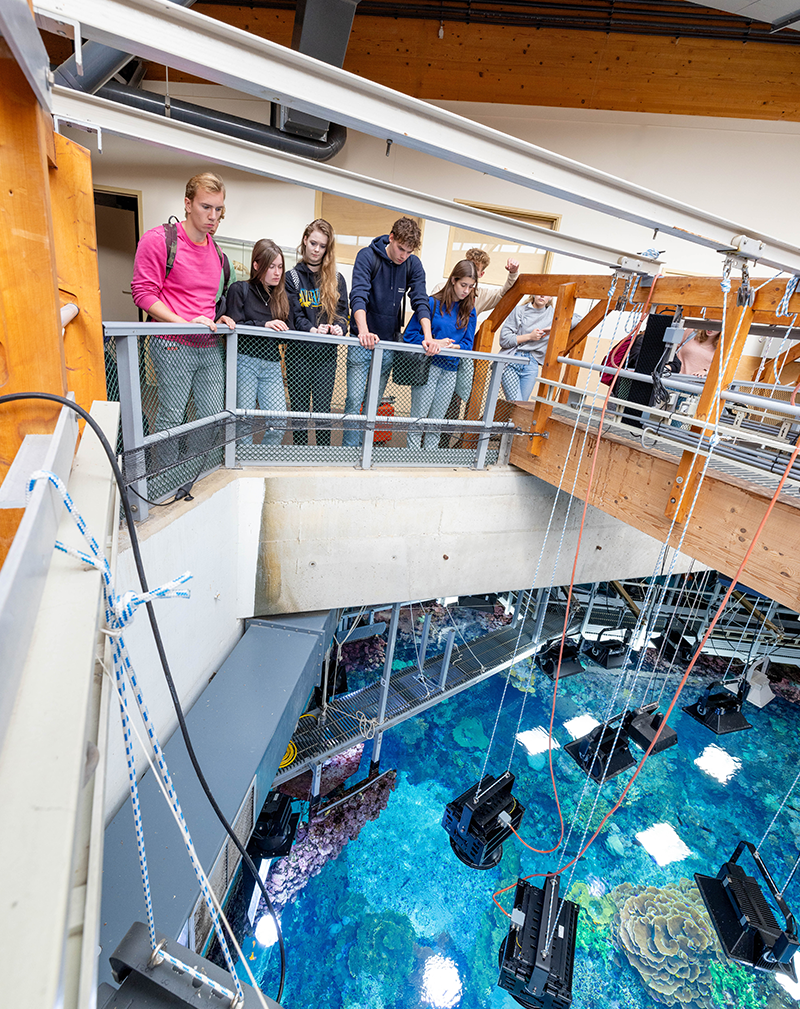

So now it is time to take a look behind the scenes at the aquarium. The guide opens a ‘secret’ door with a staircase behind it. ‘You can already smell the saltwater,’ comments a student as he steps out of the dark public area of the aquarium into the lit stairwell. Guide Peter turns around at the top of the stairs. ‘It goes without saying perhaps, but please don’t touch anything: any change can be disastrous for the balance in the ecosystem.’ He opens the door and the students enter an area located a few metres above the coral aquarium. They peer down over the railing into the water. High in the water hang dozens of lamps.

On an excursion to Den Oever, we talked to fishers themselves. That makes an impression on you

Janse explains how the lamps simulate a diurnal rhythm, and why that is important for aquarium dwellers, and then they embark on a tour of different filter systems, the quarantine room (which also gets used as a coral and animal hospital and a nursery for leopard shark eggs, for instance), and a lookout point above a giant shark tank. ‘This tank is 33 by 17 metres, six and a half metres deep, and holds three million litres of water,’ he tells the students. A student asks why one of the sharks has been separated from the rest. ‘He’s a bit too pushy so we’ve separated them for a while to protect the females.’

A bit later, the group moves on into a totally different world: the mangrove swamp. After a good look at the plants, sea cows and fiddler crabs that inhabit this water, the tour is over. Student Eline Gelderen (21) hangs back a while. She and her group are working on an assignment: to make a short video – a ‘knowledge clip’ about mangrove restoration. ‘On Bonaire there are fewer and fewer mangroves and they are shifting towards the sea, which has a big impact on the ‘services’ the ecosystem supplies, such as water purification, fish farming, CO2 sequestration and so on. In our video we explain what the problems are and what’s the best way to restore the mangroves.’ In this way, the students are working in groups on different case studies in the marine domain. ‘In week 6six there’s a film festival in which we watch each other’s videos and pick a winner.’

Switch

Gelderen initially came to Wageningen to do a degree in Biology. ‘But it was too science-oriented for me, so I took a gap year. And in that year, I heard about this new Bachelor’s programme. It appealed to me because it combines different disciplines. We get lectures about the deep sea, river mouths, the North and South Poles, and socio-ecological systems. We learn about policy, law, marine economics, ecology and genetics. That combination of the natural and the social sciences prompted me to make the switch.

If we simulated today’s natural conditions, our coral reef would be half-dead

We deal with topics that are often in the news. We had already heard about the problems facing fisheries in our lectures, but on an excursion to Den Oever we talked to the fishers themselves. That makes an impression on you.’

Meanwhile, student Jasper Dhont (18) and his group are working on a case study about diving tourism in Raja Ampat, Indonesia. ‘That is one of the most biodiverse marine locations on Earth,’ says Dhont. ‘In the last two decades, diving tourism has increased tremendously there. In combination with global warming and more pollution, it has been destructive for the coral reef.’ His group is looking at whether ecological conservation and economic development can go hand in hand. ‘We’ve held lots of discussions so we can research what the problem is, what the drivers of change can be, and how we can manage solutions.’

Monitoring whales

International students are finding the new degree programme too: 16 of the 108 Marine Sciences students come from abroad. Saba Hajek Groenendijk (19) is one of them: she is Peruvian with Dutch roots. ‘Peru is very biodiverse and that is largely due to the Humboldt Current, a cold ocean current off the coast. Our anchovy fishery is famous too. I was already interested in that sort of thing when I was little.’

After finishing secondary school Groenendijk had a gap year and worked as a volunteer on a whale-monitoring project in the north of Peru and Ecuador. ‘They look at the migration patterns of whales between Ecuador, Peru and Chile. You can use that data to decide on the best location for a marine reserve between those three countries.’

Problems in the marine domain call for a holistic, interdisciplinary approach

After her gap year, Groenendijk wanted to go to university in the Netherlands. ‘When I read that this degree programme would be run for the first time this year, I saw that as a sign.’

Groenendijk thinks the broad scope of the programme might come as a bit of a shock to some students. ‘Besides marine biology and ecology, it’s also about relations between humans and nature, socio-economic challenges, and the law. It’s a lot, but it’s good to approach problems from different perspectives.’ Groenendijk dreams of working on the Galapagos islands after graduating. ‘Or on that whale-monitoring project again.’ But she’s cautious at this point. ‘We’ve only just started on the degree. I’m curious to see how I feel at the end of it.’

Students have plenty to see in the Burgers’Zoo tunnel aquarium. Text Luuk Zegers and Dagmar Fehrmann. Photos Eric Scholten.

Students have plenty to see in the Burgers’Zoo tunnel aquarium. Text Luuk Zegers and Dagmar Fehrmann. Photos Eric Scholten.