Former WUR rector Cees Karssen passed away at the age of 86 last weekend. He held the position of rector of Wageningen University from 1993 until 2000 and was one of the initiators of the collaboration between the university and the agricultural research institutes. Despite it being one of his administrative highlights, he received ample criticism from outraged professors, he told Wageningen World (part of Resource) in 2013.

Up until the start of the nineteen nineties, the DLO institutes and the agricultural university were no more than neighbours. There was no need for mediation, but the relationship was not exactly close. The university was responsible for fundamental research and teaching while the institutes (most of which were also based in Wageningen) gave the Ministry of Agriculture advice and did applied research for the private sector.

There was the occasional border dispute but on the whole the two coexisted peaceably without much interaction. Until 1996, when the Minister of Agriculture, Jozias van Aartsen, ordered them to set up house together.

Insiders say nobody disputed at the time that something needed to be done with Wageningen. DLO and the university were each too small to continue as independent entities, let alone build up an international reputation. The institutes were running at a loss but it was the university that gave the most cause for concern. The intake was getting smaller every year. The number of students fell from 6700 in 1987 to 3800 in 1997. In 1996, the board of Utrecht University even sent a letter proposing an ‘alliance’, noting pointedly that their Veterinary Science faculty rejected as many students in any one year as enrolled in Wageningen overall.

Flirting

Five years ago, Van Aartsen told the Wageningen university magazine Resource in an interview that at the time the Ministry of Education had been in favour of a takeover by Utrecht. Jo Ritzen, the Education minister, repeatedly brought up the subject of the falling student numbers in cabinet meetings. His staff had long been exasperated by the fact that agricultural education was outside the scope of his ministry. They found this arrangement illogical and expensive. But Van Aartsen, helped by the minister of Economic Affairs Hans Wijers, would not budge so Ritzen gave up. He probably also assumed the university’s position was so hopeless that it would end up in the arms of Utrecht anyway. When things eventually turned out differently and Wageningen started flirting with DLO, Utrecht even sent an angry letter. The Utrecht board accused the university in Wageningen of being too ‘standoffish’, as a result of which ‘the agricultural university was running the risk of becoming too unattractive a prospect in the marriage market’.

In 1995, in a restaurant near The Hague, Jozias van Aartsen told the agricultural university directors that he would be asking the politician Bram Peper to advise on what to do with the agricultural university, DLO, the experimental stations and the agricultural universities of applied science. But Van Aartsen did not put forward a detailed proposal. ‘He was much too smart for that,’ says former rector Cees Karssen now. A concrete proposal generates more resistance than an exploratory study.

Selling the merger

Cees Karssen used the threat from Utrecht to sell the merger with DLO to sceptical professors, who feared Wageningen would no longer be a real university if it had to merge with the institutes. ‘I was not afraid of that. I thought Wageningen’s added value lay in making the connection between fundamental research and specific applications. When I was a professor of plant physiology, I used to visit the seed companies to find out what their problems were because I thought that was Wageningen’s raison d’être.’

Anyway, the choice was clear in Karssen’s opinion. If the university was not prepared to join up with DLO, the only other option was Utrecht and there would not be much left of the university then.

DLO had very different worries in the mid-nineties. The institutes, which included LEI, Rikilt and the institutes that went on to become Alterra and Plant Research International, were part of the Ministry of Agriculture. But they were now to become autonomous: no more drip-feeding with public money, instead they would have to bring in more funds themselves with contract research for the private sector. The impending autonomy had been talked about for a long time but now Van Aartsen decided the time had come for action.

Senior civil servant Kees van Ast had been tasked with making DLO self-financing. When it turned out that the institutes would also have to merge with the university, Van Ast simply treated that as a given. ‘No, I never considered alternatives. Not doing this just wasn’t an option.’

In the end Bram Peper recommended appointing one board for both DLO and the university. That board would be responsible for arranging a merger between the two organizations in short order. The identity of two of the members of the new board was soon clear. Karssen was the only university board member still in office, the other two having retired while Peper was working on his plan, without being replaced. ‘So then it was just me.’ The two-man DLO board was also down to one man since the illness of the director Mannes Heuver, so Van Ast became the second member of the new board. After six months of uncertainty, Cees Veerman was appointed chairman of the team, which now became known informally as ‘the three Keeses’.

Veerman not only had an arable farm, he had already managed a merger operation at The Greenery, an auction house, he was a professor holding an endowed chair at Tilburg and he was adviser to a number of companies.

Karssen: ‘I don’t think anyone else would have managed it. Veerman had just the right network among politicians, universities and agricultural organizations. I didn’t know anyone in the farming community.’

Never any arguments

Veerman caused a wave of culture shock by immediately getting rid of two institute directors and telling the university staff that while he was prepared to attend their consultation meetings, he had no intention of making any major changes to his plans. They were not used to this at the democratically run university. So while Veerman was clearly not a man to avoid conflict, the board members hardly ever fell out on anything, say Van Ast and Karssen. ‘I’ve never worked in such an effective and pleasant team in my entire career as when we were the three Keeses,’ says Karssen. ‘We never got in each other’s way’. Van Ast: ‘Veerman said when he was appointed that he wasn’t a details man; someone else would have to take on that job. So that’s what I did.’ The university remained sceptical about the plans for some time, says Karssen. ‘Many people were afraid fundamental research would suffer. Lots of the professors thought ‘applied’ was a word to be avoided if at all possible.’ The atmosphere at DLO was more accommodating. ‘It was the director of the animal sciences institute ID-Lelystad who insisted we include the word ‘university’ in the name. So the working title of Wageningen Knowledge Centre eventually became Wageningen University & Research centre, normally shortened nowadays to Wageningen UR.

Budge cut

The new board had its first big setback in 1998. In the negotiations for the new Purple II coalition government (in which the left-wing ‘red’ social democrats formed a coalition with the right-wing ‘blue’ liberals), it was agreed that the university should have its budget cut by more than 20 million guilders. This was after the three Keeses had sold the merger to the mistrustful university staff by explaining that there really was no secret agenda behind the merger plans and all efficiency savings from the partnership would be ploughed back into teaching and research.

In the end, Karssen had to call on 25 professors and tell them they would be losing their chairs. ‘A miserable period,’ he says looking back. ‘It was just before Christmas and we went from one department to the next telling them the bad news. Awful.’ Van Ast: ‘We were furious. The ministry had always promised us we would be able to invest the efficiency benefits in new developments. But that promise was obviously of no use now. We reviewed the situation and decided there was no other option than to accept it and go on with the plan.’

The cutbacks only served to increase the feeling of discontent among the staff already, says Karssen. ‘There was no support at all. I talked until I was blue in the face, explaining we didn’t have a choice and this was what the minister had decided but I don’t think I convinced anyone at the time.’ Van Ast: ‘Cees Karssen had a tough time of it. He did have doubts whether we were on the right course but he soldiered on.’

Fifteen years on, Van Ast, who is now vice chairman of the University of Twente, and Karssen, who is retired, look back on those eventful initial years with satisfaction. The university has more students than ever – there were 7500 enrolled on 1 October 2012 – and the former board members say Wageningen UR benefits from the integration of fundamental and applied research when bidding for research funding.

Van Ast: ‘I can remember us sitting in the Junushoff with enormous cardboard ears that protesting students had put on our heads. One group after another came to tell us how stupid we were. I think you can see now that we didn’t make bad choices. The basic structure we came up with then is still in place and Wageningen is attracting more students. And I don’t think academic freedom has suffered.’ Karssen: ‘If we hadn’t done this then, the university would no longer exist.

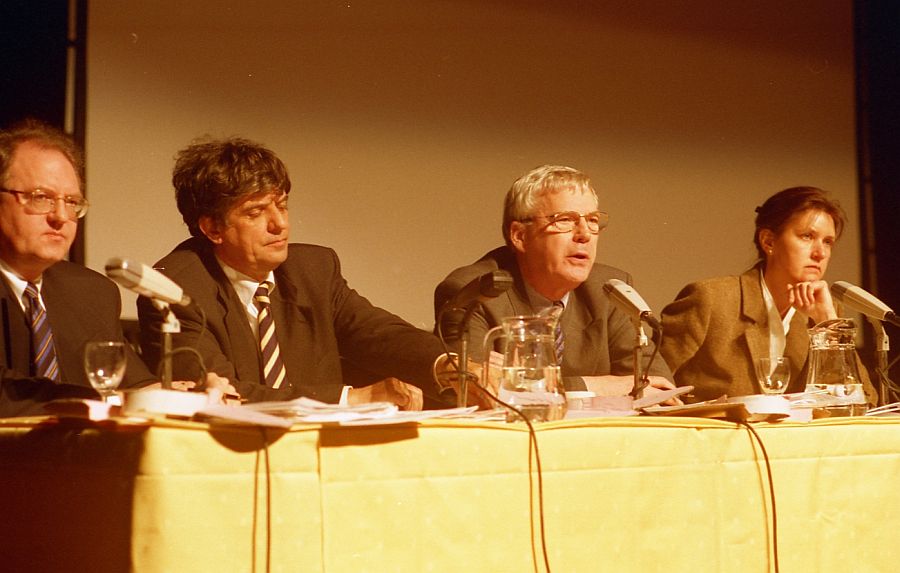

Kees van Ast, Cees Veerman and Cees Karssen in 1999, the first executive board that emerged as a result of the merger between the university and DLO in 1998. On the right Tini Colijn, general manager. PPO Photo Guy Ackermans

Kees van Ast, Cees Veerman and Cees Karssen in 1999, the first executive board that emerged as a result of the merger between the university and DLO in 1998. On the right Tini Colijn, general manager. PPO Photo Guy Ackermans