Researching fish on a desert island – it sounds like a children’s adventure story, but what is it really like? Resource delved into the world of fish monitoring on the Marker Mudflats and spent 24 hours with researchers from Wageningen Marine Research.

In a green rubber wading suit, WMR researcher Joey Volwater strides into the water in the small marina on the Marker Mudflats. After about five metres, he stops, grins and declares the water temperature ‘piss-warm’. Very different to early April, when Volwater and Amsterdam University Master’s student Elizabeth Manoloulis stood on exactly the same spot, blue in the face from the cold. Back then it was five degrees at most, and there was a chilly northeast wind. Shivering at the memory, Manoloulis had described that experience on our boat ride from Lelystad.

Research projects

Volwater and Manoloulis have made the boat trip about 10 times this season, having visited the Marker Mudflats for a 24-hour period every three to four weeks since the beginning of April. They are documenting the numbers and sizes of the fish species living there between early April, the start of the spawning season, and late September – when the fish begin their winter resting period (although that seems to be shifting due to warm late summers). This work is part of KIMA II, the follow-up to the Marker Mudflats Knowledge and Innovation Programme (KIMA) in which organizations including the Directorate-General for Public Works, Deltares and Natuurmonumenten are monitoring the development of this brand-new island chain’s ecosystem. Wageningen Marine Research is taking care of the fish research, as the Marker Mudflats have the potential to provide important habitat types for a variety of freshwater fish species.

Today, fish are also being fished for other research: the annual IJsselmeer-Markeermeer shoreline fish count. With the construction of the Marker Mudflats, these large bodies of water have gained almost 100 kilometres of shoreline, adding much more variety, which the IJsselmeer shoreline lacks. On the advice of Wageningen Marine Research, the Marker Mudflats are therefore now being included in that study by the ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality (LNV). And then there is a third study for which the Wageningers are documenting fish stocks in and around the Marker Mudflats, explains project leader Joep de Leeuw. This is a project on fish as a food source for spoonbills, for the New Land National Park.

Hauling in the net

This last research day of the season still feels summery, with a temperature of around 21 degrees, abundant sunshine and a light breeze – hence the ‘piss-warm’ water. Volwater has waded in waist-deep to deal with the net researcher Olvin van Keeken is letting out from his rubber dinghy. It is a long hatchery seine net that hangs vertically in the water thanks to floats at the top and weights at the bottom. Carefully, Van Keeken spreads the seine in a semi-circle in the water, after which he and Volwater gently pull the ends towards each other. When the circle closes, the fish swimming on the inside can only go one way: towards the bulge in the centre of the seine. When the researchers haul in the seine, it catches all the fish like a sack.

The big question, of course, is which fish are in there. To find that out, the researchers carefully empty the seine into a large plastic container with plenty of water in it. At first the fish look like one floundering, silvery mass, but they soon calm down.

The presence of young pike and rudd shows the reed beds are gaining a function as spawning grounds

Volwater wets his hands and expertly grabs the largest fish from the tank, which measures about 30 centimetres. He measures the bigger fish first, he explains, because they are relatively stress-sensitive. This one is a bream. A surprise, says project leader De Leeuw. ‘We don’t often see them this big here at this time of year.’

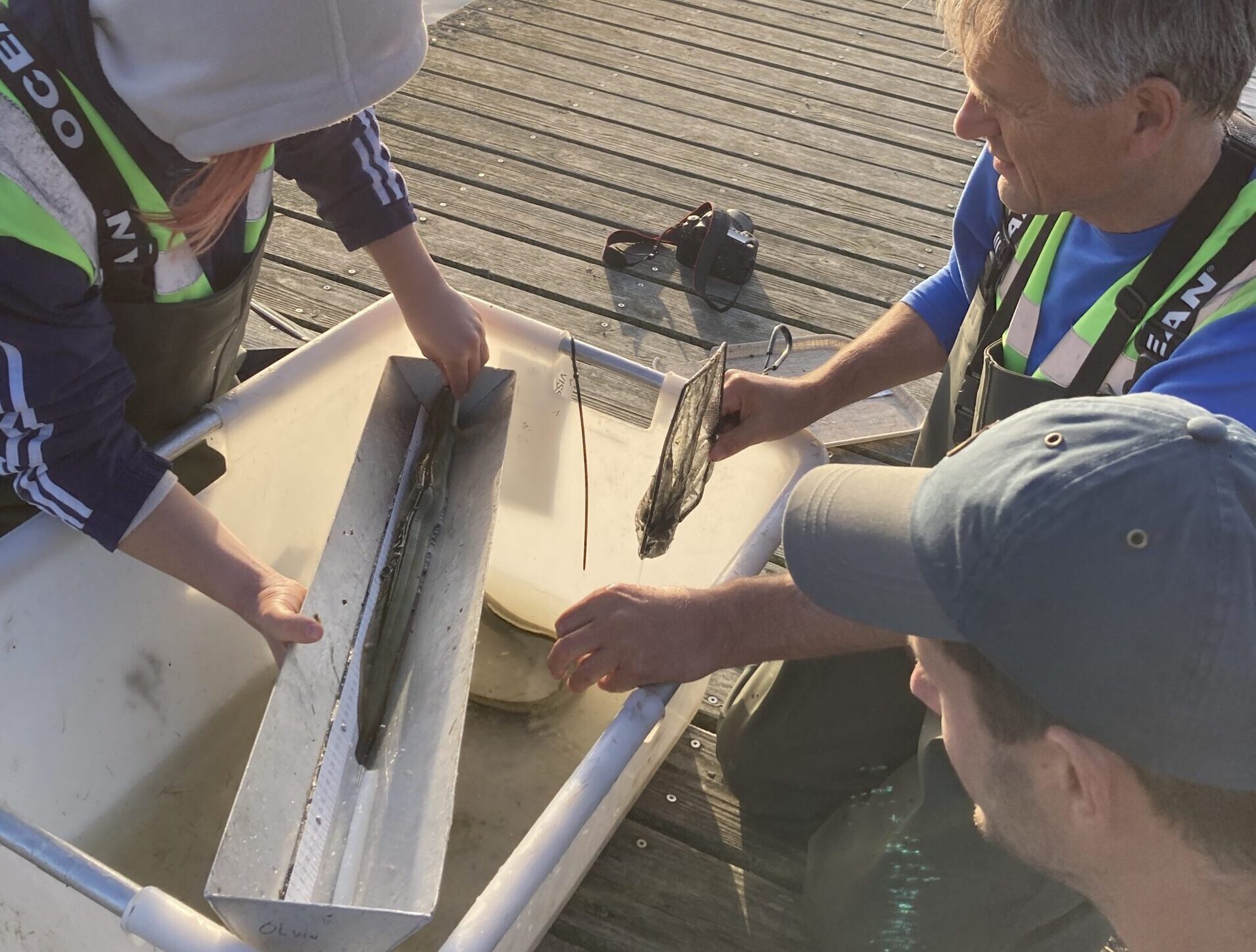

Measuring tray

The researchers determine the exact size of the fish with a measuring instrument they made themselves: a tray with a ruler screwed onto it, with a smoothly sanded gap in the rim on both sides. A thin layer of water allows the fish to slip onto the tray without getting damaged. The measuring tray simplifies the careful measuring procedure: place the fish with its nose against the crossbar, hold it firmly so it doesn’t wriggle away, and read out the size by its tail (‘in whole centimetres and rounded down’) for Manoloulis to note down. And then: whoosh, with a swift hand movement, the fish slides right back into the water through the gap in the tray’s rim.

All the fish in the tray are identified in this way. Where the lay person just sees lots of tiddlers, the researchers can identify them at lightning speed – even if they are no more than a centimetre or two long. ‘You see, this mouth is facing upwards. Then you know it’s a bleak, a surface predator, and not a roach,’ explains De Leeuw. He clarifies the identity of another tiny fish by offering it his fingertip. Snap! Obviously a predatory fish, a pikeperch to be precise.

When the bin is empty, the A4 sheet on Manoloulis’ clipboard is full of ticks: a record of the fish species identified by Volwater and De Leeuw, and of their length in centimetres: ‘Pikeperch nine. Blackmouth gudgeon four. Perch five. Ruffle four. Carp six. Roach four. Chub four. Another roach four.’ All offspring from this breeding season that are now big enough for a connoisseur to identify them. For the tiny larvae caught earlier in the season, this is done in the lab, under the microscope.

Motionless

At the next sampling location, the seine contains so many young fish that the researchers decide to work with a subsample: three quarters of the numerous small fish go straight back into the water, while a quarter of them are identified and measured. The numbers in Manoloulis’ record are then quadrupled. This keeps the data reasonably reliable, while limiting the death rate among the vulnerable young fish: the shorter the time they spend in the catch basin, the better. Because fish sampling is not entirely casualty-free; sometimes a fish will float motionless on the surface of the water after leaving the measuring tray.

Several more samples are taken that afternoon, using exactly the same procedure. If the seine does not unfold perfectly because a float is entangled in something, Van Keeken intervenes immediately: ‘Stop again!’ After all, for the catch results to be scientifically comparable, it is important to take the sample in the same way every time. ‘In the riparian sampling project, Olvin (Van Keeken, ed.) is our scientific role model,’ says De Leeuw half-jokingly – and that’s certainly how it seems, with Van Keeken directing operations every time the seine net is hauled in.

Traps and wings

In the early evening, it is time to set the traps, in little waterways of different habitat types that connect the open water with the creeks deeper in the ‘interior’. This too is done with great precision: one trap for outgoing fish and one for incoming fish, right opposite each other, and the position of the ‘wings’ of the traps prevents fish from swimming past them.

Dawn the next morning paints the sky and water of the Marker Mudflats bright orange. The first place where the traps are emptied is ‘flamingo’: the researchers named the trap locations after an exotic bird they saw there. In addition to the usual fish species, the traps also appear to contain two spotted American crayfish and some sturdy-looking eels. The crayfish get parked in a cuvette for a while, so that Utrecht University student Eggert can have a good look at them. She is researching invasive exotic species.

For the eels, the researchers produce a new homemade measuring instrument, the ‘eel flume’, which saves both humans and fish the awkwardness of attempts to get hold of such a slippery customer. The eel flume makes the measuring a lot more relaxed: add a layer of water, manoeuvre the flume under the eel in the trap, wait for the eel to stretch out, and then quickly read the size, dictate it to Manoloulis and let the eel slide back into the water.

Establishing reedbeds

At the next site, ‘bearded tit’, it’s obvious why the researchers gave the location this name. Dozens, perhaps hundreds of the little birds flutter around, over and in amongst the reeds. And their calls! ‘As though you were knocking two stones together,’ is how Volwater describes the sound. Besides the flock of bearded tits, the researchers also found some nice new species in the traps: thinlip mullet, ide, rudd, and a young pike.

The Marker Mudflats have given IJsselmeer and Markeermeer 100 kilometres of extra shoreline

The presence of the latter two fish in the catch tells us something about the establishment of the reed beds, Volwater explains. Reed growth on the Marker Mudflats is not yet optimal, partly due to grazing by geese and ‘unnatural’ water level management: the water is kept higher in summer and lower in winter. But the presence of young pike and rudd suggests that the reed beds are nevertheless gaining a function as spawning grounds for adult fish and as nurseries for the larvae and young of these typical reedbed inhabitants.

End-of-season fieldwork

The last trap is emptied at around 11 o’clock and all the fish caught are recorded. The traps and seine nets are hung out to dry at the boathouse, the dinghy’s plug is pulled out and all the materials from six months of fish monitoring are collected for carrying to the boat. When it leaves the harbour for Lelystad in the afternoon with all the research equipment and people on board, the 2023 Marker Mudflats fish monitoring season is over. The fieldwork, that is. Now for the data analysis: distilling trends, making connections and drawing conclusions. A sneak preview: 21 different fish species were found this season, including four newcomers: pike, Prussian carp, rudd and tench.

Constructed nature

The Marker Mudflats consist of seven uninhabited islands about nine kilometres from Lelystad as the crow flies, created out of about 30 million cubic metres of sand, silt and clay pumped up from the bottom of the Markermeer lake. The Netherlands once planned to reclaim the entire area, as had been done with the Noordoostpolder and the Flevopolders. The lake was sealed off with a dyke in 1976, but the planned reclamation never came, and was officially scrapped by the Dutch government in 2002. In part because it lacked natural shoreline zones, gullies and shallows, the Markermeer gradually changed over the years into, frankly, a dead tank of water full of swirling silt. To restore the lake’s ecology, work started on the Marker Mudflats in 2016. So far it is a success: the silt is settling and flora and fauna are recovering. Together with the Markerwaard, Oostvaardersplassen, Lepelaarplassen and Trintelzand, the islets form the New Land National Park.

WUR students welcome

Wageningen Marine Research will continue to be actively involved in monitoring fish on the Marker Mudflats in the coming years; KIMA II is a multi-year project. WUR students who would like to help next season and perhaps study their ‘own’ topic can apply to Joey Volwater.

The mesh of the hatchery seine net is examined carefully to check for any small fish caught up in it. From the left: MT member Cas Wiebenga (on a work visit), Utrecht University student Emma Eggert and WMR shoreline researcher Olvin van Keeken. Photo Resource

The mesh of the hatchery seine net is examined carefully to check for any small fish caught up in it. From the left: MT member Cas Wiebenga (on a work visit), Utrecht University student Emma Eggert and WMR shoreline researcher Olvin van Keeken. Photo Resource