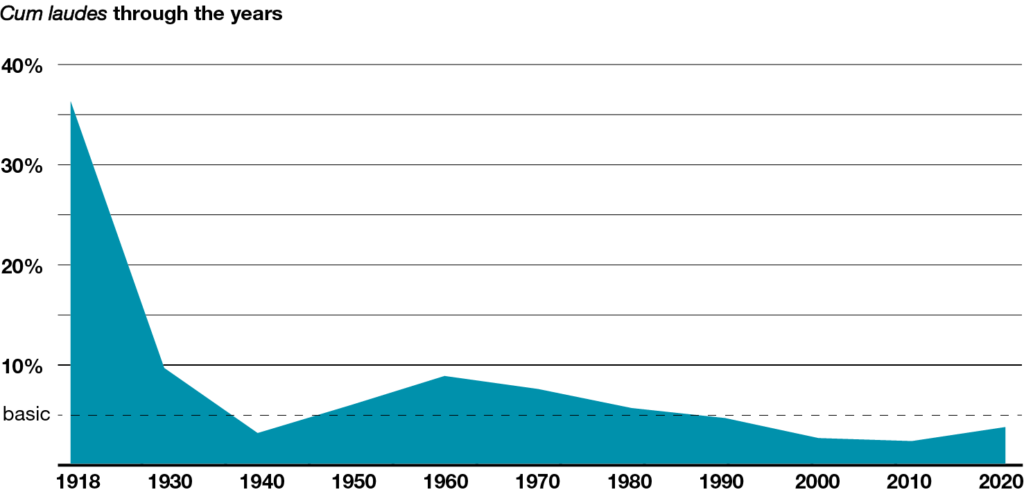

WUR aims at excellence. But for several decades that has not been reflected in the number of PhD candidates completing their programmes cum laude – with distinction. This trend started around the turn of the 21st century, suggests research by Resource, when the number fell below the national ‘norm’ of five per cent. Over the past 20 years, it has hovered around two per cent, with a low point in 2014, when only two out of 287 PhD candidates graduated cum laude, which is 0.7 per cent.

That low point is a glaring contrast with the ‘glorious years’ of the Agricultural University, when it comes to cum laudes. In the University’s first 10 years from 1918, as many as 36 per cent of PhD candidates (18 out of 50) graduated cum laude. In the subsequent decades, that proportion rapidly fell to less than 10 per cent, dropping below the lower limit early this century – a development that coincided with a massive growth in PhD numbers in the last 30 years.

Supervisor

The meagre harvest of cum laudes has not escaped the attention of the Academic Board, says Dean of Research Wouter Hendriks. In an effort to turn the tide, the procedure for awarding cum laude has been adjusted in several respects in recent years. One of the main changes is that the initiative for awarding cum laude no longer lies solely with the examining committee but also with the supervisor. ‘It used to be up to the four ‘opponents’ to say that the thesis was worth a cum laude,’ explains Hendriks. ‘The supervisor would then be asked if he or she supported that. Then two new opponents were asked to assess the thesis. That’s been changed and now the supervisor can take the initiative by submitting a letter to the opponents with the thesis, asking them to consider awarding cum laude.’

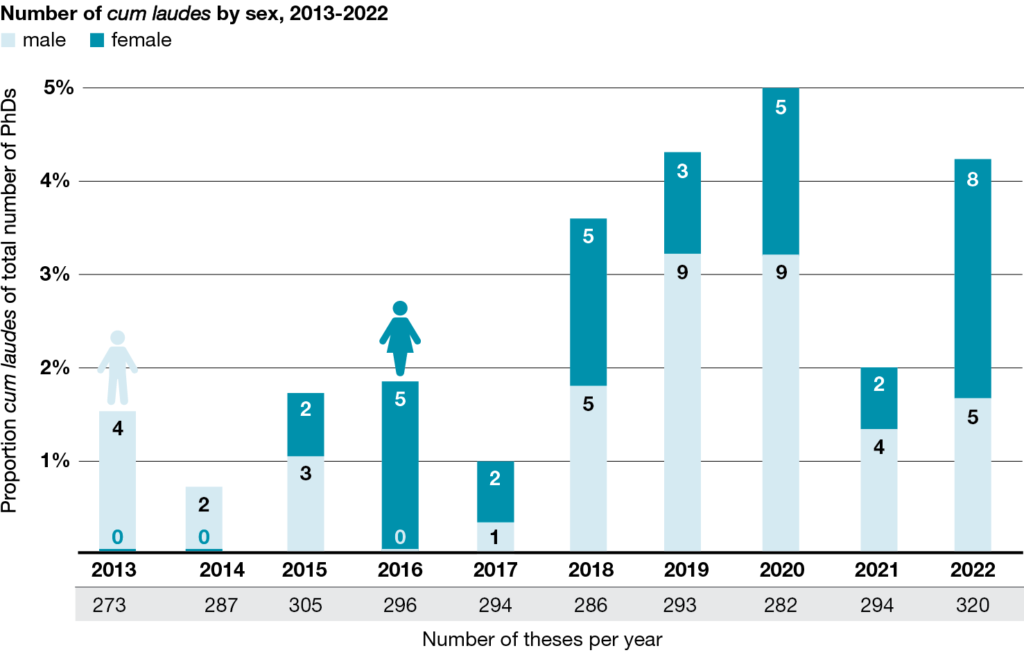

On top of this, the assessment by the four opponents has become less stringent. The bar for cum laude used to lie at a minimum of three ‘excellents’ and one ‘very good’. Now the lower limit for considering cum laude is two ‘very goods’ and two ‘excellents’ or one ‘good’ and three ‘excellents’. And the assessment has been made more objective by introducing rubrics – scoring tables. This new approach appears to be working, judging by the number of cum laudes in the past 10 years, which has been going up since 2017 and is currently back up to four per cent.

It’s good that you can now share your impression of the candidate with the opponents at an early stage

It is only right that the initiative for a cum laude should lie with a PhD candidate’s supervisor, says Professor John van der Oost. With eight cum laudes to his name, he is the undisputed king of cum laude at WUR. None of the professors has produced more cum laude graduates in the course of their careers than he has. ‘An opponent doesn’t usually know the candidate very well. So they have to assess them on the basis of their thesis, which includes chapters that have been co-written with others. Once the work is published, it’s been tinkered with a lot. It’s good that you can now share your impression of the candidate with the opponents at an early stage in a half-page statement.’

Women

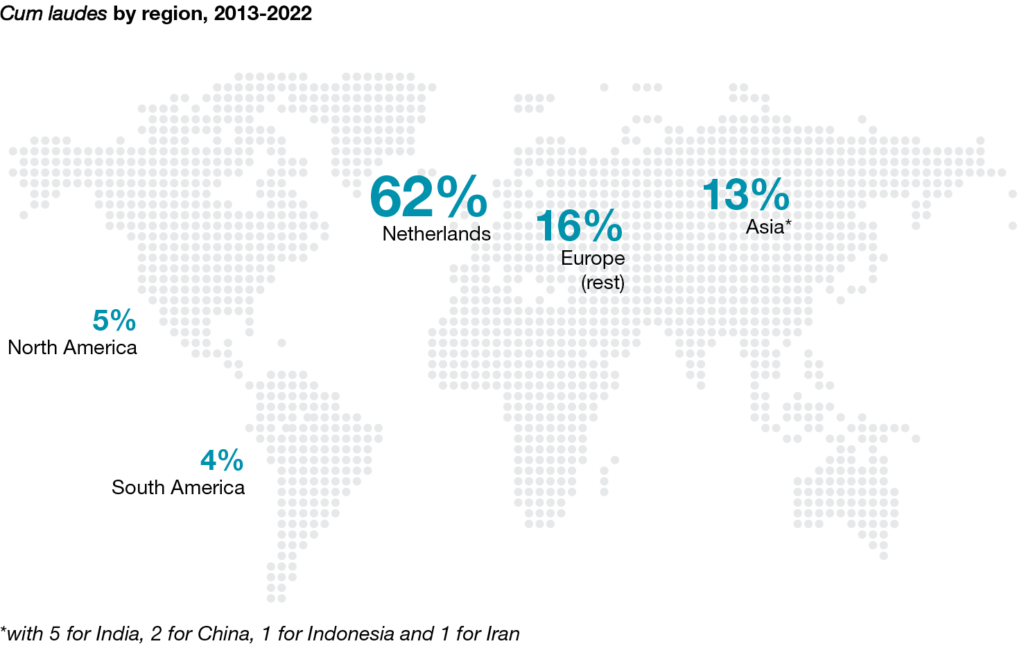

So the number of cum laudes is moving in the right direction. But there’s another story that the statistics tell as well. And that is that cum laude is unevenly awarded. Women and international PhD candidates don’t come off well. Of all the women PhD candidates in recent decades, only 2.2 per cent passed cum laude – as opposed to 2.9 per cent of men. The bias is even bigger in the case of international PhDs: although 60 per cent of the candidates are international, they only receive 39 per cent of the cum laudes. Non-western PhD candidates score particularly poorly. Not a single African graduated cum laude. The large contingent of Chinese PhD candidates netted two cum laudes. A big exception is India, with five cum laudes.

The gender bias has been noted at other universities too. But the WUR figures were new for Hendriks. But, striking as they are, on closer scrutiny he concludes that the difference is not statistically significant. It could be a matter of chance. The low score among international PhD candidates is definitely not coincidental, however. Hendriks thinks it’s down to cultural differences. ‘The admission requirements for our PhD programme are the same for everyone. But while a Dutch PhD candidate doesn’t take long to adapt to the programme, a foreign candidate is faced with a whole new culture. So it may take them longer to integrate and get used to how the courses are run.’

Cultural differences

That cultural factor is the strongest for PhD candidates from South-East Asia. ‘A supervisor is treated with great respect by someone from that region. In the Dutch culture it is normal to question and discuss things. That is not a natural response for a South-East Asian. They are more inclined to do as their supervisor tells them.’ Hendriks cannot say for sure whether that leads to poorer work, content-wise. ‘It may be – but this is just a hypothesis – that they put less of themselves into their research, because of that cultural difference. Fewer of their own ideas.’ Van der Oost confirms the importance of initiative. ‘During their PhD research, a candidate is supposed to develop into an independent researcher. The more maturity they show in the way they think up and run experiments, and analyse and write up their results, the higher they score. Taking initiatives and entering into collaborations are very important to that.’

Van der Oost’s 54 PhD candidates, eight have passed cum laude. That is 15 per cent. How does he do it? ‘A good atmosphere is important. I simply want to have nice people in the group. And of course, it is a nice extra if PhD candidates are also smart and hard-working. Many of our PhD candidates were here for their Master’s too. So you know who you’re dealing with. I also give my students a lot of freedom. When PhD candidates come to me with a good plan that they really believe in, I let them implement it, even if I don’t think it will succeed. That was how my own CRISPR research started back in the day, too. In 2005, I had just been given a large Research Council grant when we happened upon CRISPR. I put two people to work on that. I took that liberty and it worked out well.’

In fact, that new research field may go a long way to account for his cum laude success rate. ‘CRISPR is hot. That makes it easier to get published in journals with a high impact factor. And that goes down well with an examining committee.’

Hendriks points to the same advantage. ‘Microbiology is all the rage at the moment. My chair group, Animal Nutrition, doesn’t have many cum laudes. There’s nothing wrong with our science, but we’ll never get into Nature or Science. That’s very difficult to do in our domain. Our scope is too broad for that. Anyway, it’s harder for a small chair group to achieve the same level as a larger chair group can. That’s because of the advantages of scale, which gives you more apparatus, greater mass and more collaboration.’

Excellence

In spite of his stunning score, some of the blame for the gender bias can be laid at Van der Oost’s door. ‘Of the eight cum laudes, the first five were white Dutch men,’ he admits. ‘The last three were non-white foreigners, one of them a woman. The gender bias is certainly very big, but it has nothing to do with gender-based selection. That’s not how I work at all. It reflects the students who come here, and that has to do with the subject area. I have no influence on that. But it does seem to be going in the right direction: one quarter of the students in the group are women. And more than half the 12 post-docs we have appointed in the last three years are women.’

If your goal is excellence, you’ve got to acknowledge it too

Could the inequality in the awarding of cum laude be a reason to scrap the system? Hendriks has no time for that idea. ‘Basically, this is about whether you want to differentiate or not. If you only assess whether a thesis merits a PhD, the quality doesn’t matter anymore. It makes no difference whether you get a six or an eight. If a six is enough, where’s the incentive to do more? If your goal is excellence, you’ve got to acknowledge it too. Science isn’t about “good enough”, science is about delivering quality.’

Cum laude, and then?

Cum laude looks good on your CV. But does it help you in your career? All eight researchers who got cum laude with John van der Oost have done well, anyway. The first, Thijs Ettema (2005) is chair-holding professor of Microbiology, so he’s Van der Oost’s current boss. Stan Brouns (2007) was recently appointed full professor at Delft. Matthijs Joore (2010) is an assistant professor at Nijmegen and has a Vidi grant in the bag. Edze Westra (2013) is a full professor at Exeter, with an ERC grant. Daan Swarts (2015) is an assistant professor in Biochemistry and recently got a Vidi. Prarthana Mohenraju (2019), de only woman in the group, is a postdoc in Leiden and has a Veni grant. Ioannis Mougiakos (2019) left for Germany with a Rubicon grant, but is now a senior researcher with a company in Denmark. Mihris Naduthodi (2021) is working in New York, with a Rubicon grant. But graduating cum laude isn’t everything. Van der Oost himself did not graduate cum laude, but he did win the Spinoza prize in 2018.

Cum laude is unevenly awarded. Women and international PhD candidates don’t come off well. And non-western candidates score particularly poorly. Illustration Valerie Geelen

Cum laude is unevenly awarded. Women and international PhD candidates don’t come off well. And non-western candidates score particularly poorly. Illustration Valerie Geelen