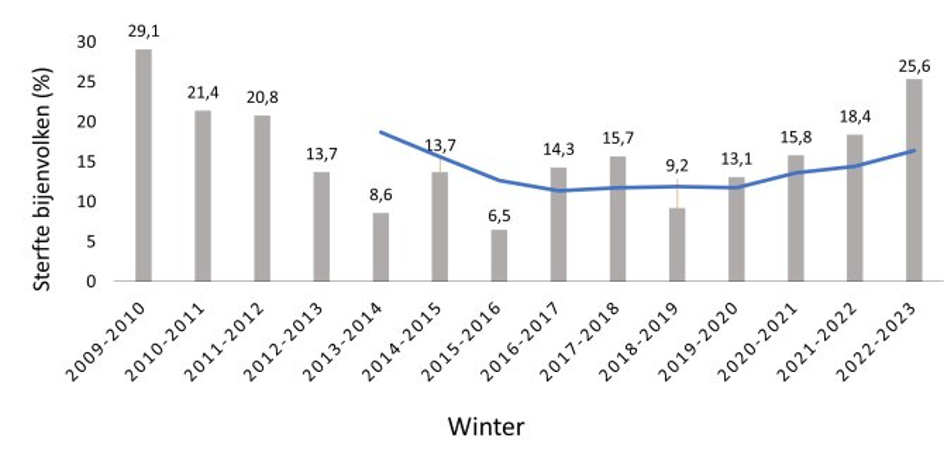

Over one-quarter of the Dutch honeybee colonies perished last winter, say Dutch beekeepers. This puts winter mortality at a level that has not been recorded since 2010. This is shown by WUR’s annual monitoring.

In 2019, Resource wondered what the state of play with bee mortality was. Returned with a vengeance, this year shows. Out of the 2779 interviewed Dutch beekeepers, 280 reported they had lost all of their bee colonies.1075 had not lost any colonies. With a 41.6 per cent mortality rate, Utrecht ranks highest, while Limburg ranks lowest with 16.6 per cent mortality.

A clear reason for the high winter mortality can not be given, says honeybee researcher Harmen Hendriksma. ‘Basically, we have all the usual suspects lined up.’

Weather conditions

Hendriksma indicates that the weather conditions may be to blame. The summer of 2022 was dry, and the winter was mild. The persistent drought may have negatively impacted the availability of food in the immediate environment. Moreover, the autumn lasted longer than normal due to the higher temperatures, which kept colonies from going into winter mode. ‘They continued to reproduce while the food supply was waning. Particularly the availability of pollen, which beekeepers cannot replace with the sugar water with which they feed their bees in the winter.

However, according to Hendriksma, the emergence of the Asian hornet, which was the subject of recent news reports indicating it has been sighted in almost all Dutch provinces, is unlikely to be related to bee mortality. ‘The Asian hornet may certainly pose a danger to a colony: if there is a predator near the hive, the bees will be afraid to forage. But the Asian hornet is not all that prevalent here. Unlike Belgium, where there are hundreds, if not thousands, of nests. Moreover, Limburg and Brabant show relatively low bee mortality, while the hornet is more common in those provinces.’

Varroa

A more likely explanation is that the varroa destructor contributes significantly to winter mortality. This parasite reproduces in the bee brood and often introduces pathogens. The deformed wing-virus, which causes deformed wings, is an example. The parasite also indirectly contributes to stunted development among bees. ‘And if a bee colony enters the winter period already weakened, the risk of mortality is significantly higher. The varroa is known to be related to winter mortality,’ Hendriksma emphasises.

However, other factors may also play a part. How the bees are kept, for example. ‘Some inhabitants of the metropolitan areas have taken to beekeeping. However, novice beekeepers do not yet have the right sensitivity to assess their colonies’ health that experienced keepers have. Some choose not to use anti-mite products but try to increase the colonies’ resilience through natural selection, accepting higher mortality as a trade-off.’

Itching

To gain insight into winter mortality and its causes, the data from the survey will be further analysed. The beekeepers have also been questioned about their feeding and pest control habits. The results of this analysis are expected in the course of this year. Hendriksma hopes funding for multi-year research will become available. ‘I’m itching to get a grip on winter mortality.’

The COLOSS survey (COlony LOSSes) is conducted annually in 40 countries. Winter mortality in Belgium was also relatively high at 23 per cent. German beekeepers, on the other hand, reported a mortality of approximately 12%. The high mortality rates in the Netherlands could cause issues in the fruit-growing sector, says Hendriksma. ‘One-quarter of the colonies have perished. Not all growers will have access to the amount of bees they may want’, he predicts.

Belgium also showed high mortality rates among bees, while this was not the case in Germany. Photo Meggyn Pommerleau via Unsplash

Belgium also showed high mortality rates among bees, while this was not the case in Germany. Photo Meggyn Pommerleau via Unsplash ![[The Proposition] ‘Only beekeepers are entitled to complain about the weather.’](https://www.resource-online.nl/app/uploads/2024/06/de-stelling-1817.png)