Text Marianne Wilschut

Whether it’s about nitrogen emissions or where to discharge contaminated groundwater, members of the public are increasingly turning to the courts — despite the priority given to public participation by politicians and administrators in the past 15 years. So is that participation helping the general public? WUR and nature and landscape society Mooi Wageningen are organizing a symposium on this topic on 1 April.

It is not yet as bad as in America, but members of the public in the Netherlands are increasingly going to court, often in cases against government bodies. Last year, the highest court in the country, the Council of State, reported that the number of lawsuits dealing with zoning plans and building permits had risen by 75 per cent between 2019 and 2021. In 2021, the Council of State’s Spatial Planning Chamber had to deal with over 2300 new lawsuits, compared with 1800 in 2020.

That is despite public participation becoming a buzzword in local government in recent years. The general public has been given more of a say in plans, with citizens’ panels, thematic meetings and local ambassadors. The new Environment and Planning Act, due to come into effect next year, is one aspect of this. Members of the public are getting the opportunity to provide input in policy plans for their local area. In theory, their involvement should lead to fewer lawsuits, but that does not seem to be what happens in practice.

On Saturday 1 April, Mooi Wageningen and WUR are organizing the symposium ‘Citizens go to Court’, where they discuss whether and how public participation can prevent such court cases about nature issues. The speakers include representatives of organizations with experience of lawsuits against government bodies, such as Johan Vollenbroek from Mobilization for the Environment and Jaap Dirkmaat from the Dutch cultural landscape organization VNC. Scientists, lawyers and politicians have also been invited.

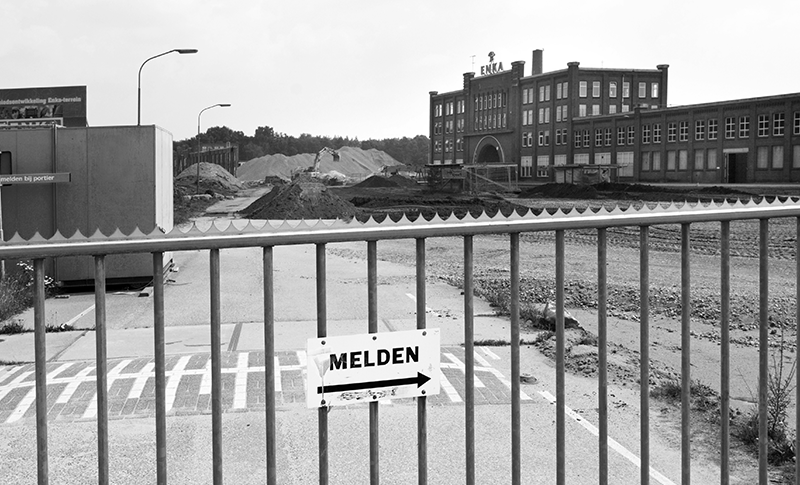

Dirty ENKA pipe

Co-organizer Mooi Wageningen has first-hand experience of legal proceedings. The society has taken cases to the Council of State concerning plans to build a golf course on De Dorskamp country estate, plans for a solar farm on Haarweg and the intended discharge of contaminated groundwater from the ENKA site into the Lower Rhine.

‘The court ruled against us in two cases,’ says Raoul Beunen, Mooi Wageningen board member and associate professor of Environmental Governance at the Open University, ‘but our lawsuits still set things in motion.’ In the example of the ‘dirty ENKA pipe’, it led to additional investigations and ultimately the decision not to go ahead with the discharge. Beunen: ‘In almost all the environmental and spatial planning issues, you see things only really start to change once advocacy groups go to court. It is that situation that made us as a society decide to organize this symposium. We also wanted to discuss with scientists how you can design participation processes that genuinely give members of the public a role. That is often disappointingly limited at present.’

In practice, public participation is often for show

Roel During, WUR researcher Social Innovation and the Democratization of Environmental Issues

‘In practice, public participation is often just for show,’ agrees Roel During. He studies social innovation and the democratization of environmental issues as a researcher at WUR and is one of the speakers at the symposium. ‘There isn’t much scope for members of the public to put forward their ideas about building plans in their local area, and the need for the plans and their supposed benefits are almost never questioned. That leads to frustration. It’s really political impotency that drives people to turn to the courts so often.’

One of the explanations During gives for this trend is the fact that public authorities have increasingly adopted the role of property developer. ‘In that role, you are more likely to face members of the public who don’t agree with your plans. They are then seen as an obstructive force. So the authorities try to enforce their plans by making processes as opaque as possible. That is called “black boxing”. Take the example of Lelystad Airport. The Ministry of Transport hired various agencies to develop complicated models of the expected noise nuisance. But the government underestimates the knowledge and expertise of the general public.’ In that instance, engineers living near the airport were able to show the ministry’s numbers were wrong.

Losing out

Lelystad Airport was a victory, but members of the public who go to court usually end up losing out. During: ‘The Council of State assesses whether the procedures were correct, but it doesn’t look at the substance of the matter. If citizens win the case, that is often only a temporary victory because the government then changes the plans to make sure they comply with the law. Advocacy groups regularly ask me for advice. I actually advise them not to go to court, but instead to come up with an alternative plan that is cheaper and better. That’s a good way to persuade politicians.’

During is positive about the new Environment and Planning Act. ‘Municipalities have to draw up vision documents giving their core values in such matters as nature and health. Then an application to build a new data centre, say, can be assessed against that vision. There will be more opportunities for advocacy organizations to have input, as long as they are open to contributing ideas during the preparation of the vision document.’

Beunen is less optimistic. ‘The real decisions are taken not in the vision document but in the environment plan and individual projects. And the new law gives government bodies more scope for applying the rules flexibly. That means citizens have fewer possibilities for objecting to plans that conflict with the established core values.’

‘Going to Court’, Saturday 1 April from 14:30 to 17:30, Impulse.

Tickets

Natuur- en landschapsvereniging Nature and Landscape Association Mooi Wageningen took ENKA to court to prevent it from discharging contaminated groundwater into the Lower Rhine. Photo: Bert Spiertz/Hollandse Hoogte

Natuur- en landschapsvereniging Nature and Landscape Association Mooi Wageningen took ENKA to court to prevent it from discharging contaminated groundwater into the Lower Rhine. Photo: Bert Spiertz/Hollandse Hoogte

this article misses the important last sentence and disagreement that is part of the Dutch article:

Beunen is minder optimistisch. ‘De echte besluiten worden niet in de omgevingsvisie, maar in het omgevingsplan en projectbesluiten genomen en daarin krijgen overheden van de nieuwe wet meer ruimte om flexibeler met de regels om te gaan. Daardoor heb je als burger minder mogelijkheden om bezwaar te maken tegen plannen die in strijd zijn met de vastgestelde kernwaarden.’

Hi Wieke, thanks for the heads up. This last sentence got lost somewhere else in the text. It is now in it’s right place.