Environmentally friendly behaviour doesn’t happen of its own accord, but you can encourage such behaviour. That is the message from the research that got Lieke Dreijerink her PhD last week. She studied the classic gap between what people think and what they do, focusing on the environment.

Why do we want to do what’s best for the environment and nature, but find it so difficult to put that into practice? Dreijerink specifically studied what is termed behavioural spillover.

A spillover is when one behaviour has a knock-on effect on other behaviours. Dreijerink: ‘There is positive spillover if one sustainable behaviour leads to another one. Negative spillover is if doing something environmentally friendly is followed by something that is not good for the environment. As if people think: I just did something good so now it’s okay to lapse a bit.’

Gift

Dreijerink demonstrated the existence of negative spillover in an experiment where the participants had to assess images of unsafe cycling situations. ‘In one group, the environmental benefits of possible solutions were underlined, while in the other group the financial advantages were emphasized. That was the first behaviour. As a reward, the participants got vouchers to spend on a gift — the second behaviour.’

The gifts varied in their environmental impact. Most people chose gifts with a negative environmental impact. ‘That’s negative spillover,’ explains Dreijerink. But the experiment also had a positive finding. ‘If information was given about the environmental impact of the gifts, people made greener choices, especially if they had been in the “environmental group” for the cycling task. So you can combat negative spillover, and information plays a role in this.’

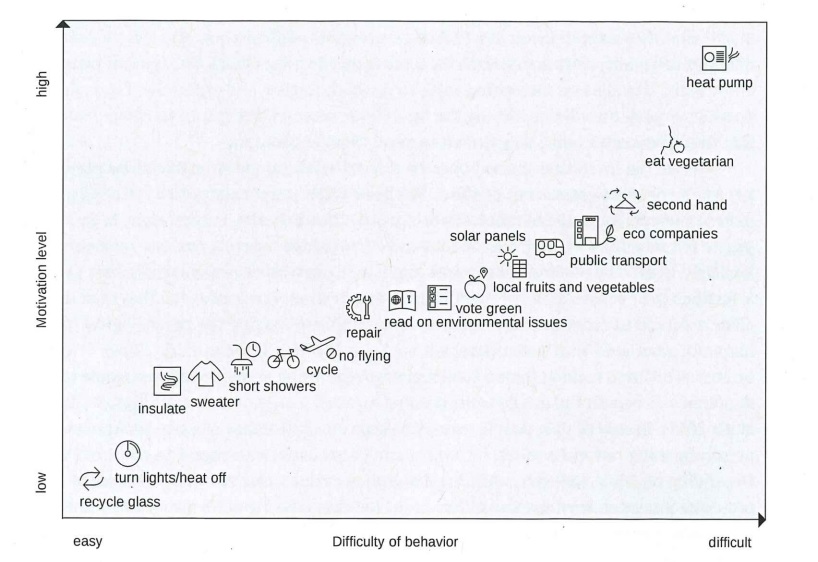

You can also influence behaviour by taking people’s motivation into account. In a survey of over 1500 people, Dreijerink presented 17 examples of environmentally friendly behaviour — from recycling glass to buying a heat pump — and asked whether they did that. ‘You can use a ‘Rasch analysis’ to determine how difficult a certain behaviour is and the associated level of motivation required.’ If you plot the behaviours in a chart, you get a kind of ladder.

Springboard

The ladder has practical uses. Dreijerink: ‘At each level of motivation, you see what kind of things people do in terms of sustainable behaviour and what the next step is.’ Everyone finds it easy to recycle glass, so not much motivation is required. But a lot of motivation is needed to become vegetarian or buy a heat pump. ‘This ladder helps you come up with specific measures to encourage people to go one step further.’ It is even possible to quantify the relationship between different kinds of behaviour. For example, if someone travels by public transport, they are 10 per cent more like to buy products from ecological stores. Dreijerink: ‘So one behaviour can be a springboard for the next environmentally friendly step.’ But that does require policy-makers to take action. ‘You can’t assume one environmentally friendly behaviour will automatically lead to the next one. You need to offer targeted support for both behaviours.’

Photo Shutterstock

Photo Shutterstock