Text: Nienke Beintema

Here they come, walking through the narrow passage in an orderly line. The dairy cows at Dairy Campus in Leeuwarden are returning to their barn, freshly milked and checked.

There are two cameras suspended in the corridor, pointing at the cows as they pass by. Back in the milking carousel, their hooves have already been automatically photographed. And there is more equipment up ahead in the spacious barn: another eight cameras, plus four anchors positioned high up in the four corners. These anchors pick up signals from tags the cows wear on their collars. The tags emit high-frequency radio waves with which a computer track sthe exact position of every cow. Together, these systems locate the cows on the farm 24 hours a day, and know whether they are moving fast or slowly, eating or resting, standing or lying down.

Painful swelling

‘This system is part of our innovation programme called Next-Level Animal Sciences,’ says Claudia Kamphuis, a researcher at Wageningen Livestock Research. ‘We are studying the use of sensor technology in combination with artificial intelligence to monitor particular health traits and the welfare of farm animals.’ One of the things this project focuses on is Mortellaro’s disease, a common bacterial hoof infection that causes painful swellings. The disease not only makes it harder for animals to walk, but also makes their stools looser and affects their general health, their fertility and their milk yield. It is a contagious disease, which, according to some estimates, affects 40 per cent of Dutch dairy cattle.

Ideally, farmers aim to detect the infection before the cow has visible inflammation, explains Kamphuis. ‘We are investigating the extent to which sensor technology can help with that early detection,’ she says. ‘Then farmers can treat their cows sooner, preventing any further spread of the disease.’

This research is taking place at Dairy Campus, a high-tech experimental farm run by Wageningen Livestock Research with several partners.

It’s nicer for the farmer to work with healthy animals too

Here, all cows wear the kind of collar with an identification chip that many dairy farmers have adopted to make their operations more efficient. ‘What our sensor technology adds is the behavioural monitoring aspect, says Kamphuis. ‘That fits in with the development we are seeing: society and farmers alike are going to give increasing importance to animal health and welfare. Farmers with large farms can’t keep a close eye on every cow. That’s why we are keen to automate that.’

Limping

The images from the cameras in the passage are automatically analysed with image processing techniques. ‘Together with our colleagues in the Agricultural Business Technology chair group, we created a model that identifies 17 key points on the cow,’ says Kamphuis. ‘Taken together, these tell us something about the cow’s gait. Things like the curvature of the spine, or the stride length, or the extent to which the head moves up and down. If this system tracks an individual cow daily, it “learns” what that cow’s normal gait is like, and can sound the alarm if there is any change, perhaps because the cow is limping.’

The researchers are now ‘training’ this system by manually validating the data. They do this by viewing and analysing images, and by looking at automatic photos of the hooves taken during milking.

The four sensors in the barn record the cow’s position in two dimensions to the nearest centimetre. The researchers use camera images to manually validate the data from this system, but also to record other details about the cow, such as whether she is standing or lying down. ‘You can derive a lot of information about a cow’s health from those patterns,’ says Kamphuis. ‘How long does it take the cow to get up, for example, or to lie down? If a cow is in pain, we expect it to take longer than usual. So far, we have never collected that information systematically.’ Here again, the earlier you detect health problems, the better you can treat them, Kamphuis emphasizes. ‘That is better for the cow, but it’s nicer for the farmer to work with healthy animals, too.’

Prototype

In time, the researchers believe they will be able to collect all the information farmers need with the cameras – without the 3D location. ‘Thanks to the combination with position measurements, we can now develop very efficient image-processing software for this purpose,’ says Kamphuis.

‘The NLAS innovation programme on Dairy Campus will run until mid-2023, by which time Kamphuis hopes to have a prototype ready. How realistic is it that these technologies will then be adopted in barns around the Netherlands? ‘The use of cameras is definitely going to take off; I have no doubt about that, replies Kamphuis. ‘The cameras are relatively cheap, whereas the sensor for the 3D tracking are still expensive. But eventually we hope that we won’t need those anymore.’

More sensor technology

There are other WUR researchers working on the use of sensor technology for monitoring animal welfare, too. Wageningen Livestock Research, for example, is developing a camera system for recording and analysing the movements of broiler chickens. This system looks at the flock as a whole: the white chicks move as pixels against a black background. The changing pixels reveal exactly how the chicks are moving and the computer extracts information about their welfare from that.

Researchers at Wageningen University are developing a capsule that pigs can swallow, which contains a sensor that collects information about the pig’s digestion and health. The capsule measures temperature, acidity and the presence of certain proteins, and communicates wirelessly with a computer. The computer the deduces the health status of the pig from the data, and sounds the alarm if anything changes.

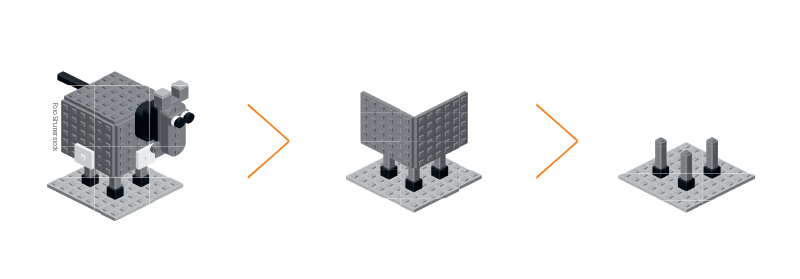

The hooves are automatically photographed in the milking carrousel. Photo Reyer Boxem

The hooves are automatically photographed in the milking carrousel. Photo Reyer Boxem