Within hours of her death on 16 October, the beached orca from Cadzand was hoisted onto the dissecting table in Utrecht with the aim of determining the cause of death. Later that week, the stomach and intestines went to Wageningen Marine Research in Den Helder for dietary analysis. Resource was an observer.

We are in the dissecting room at Wageningen Marine Research (WMR). The open door provides a view of Den Helder harbour. Daylight reflects off two sparklingly clean dissecting tables. In one corner of the lab, two people in blue coats are hunched over a black barrel. Marine biologist Mardik Leopold and his assistant and former trainee Anita van Nierop are looking at the shapeless mass of organs that half-fill the barrel. ‘These will be the intestines, so the stomach must be in that bag,’ says Leopold. They hoist a large bag onto the cutting table, tip the contents into a grey tray and start searching the organ for clues with their hands. A glance into the tray reveals a large hunk of solid meat, covered in membranes.

The smell is not too bad: it smells of blood but not of rotten fish. That’s because the animal is still very fresh. It died on Sunday night and was taken straight to Utrecht for autopsy, after which the stomach and intestines were immediately frozen. A beached whale is often somewhat decayed by the time it gets here, and then you can smell it. There’s a reason why the door is open to the outdoors.

From Spain to Cadzand

By now, there is a line of employees in blue coats watching the two at the dissection table with curiosity. It is the first orca ever to be examined at WMR. She was beached alive near Cadzand, but died in spite of a rescue attempt. The immature female turned out to be the Spanish-Portuguese Gala IB6. She had swum all the way from the waters around the Iberian Peninsula to the North Sea – an odd thing to do. In Spain, she was always seen together with a male. Near Cadzand, too, a second orca was swimming by her side, but only Gala beached herself. ‘That does suggest that she was sick,’ Leopold said. The only question is, what was wrong with her. To find that out, Leopold is investigating Gala’s stomach and intestines.

Plastic

The first stage of the stomach analysis is to cut the great hunk into manageable pieces. ‘Hey, look at this!’ Leopold’s hand emerges from the stomach with a large piece of clear plastic. The researchers get hold of a first piece of the stomach, which is white on the inside with rough folds. They rinse out these folds with a jet of water in a sink. Then they pour the water into a large glass, which they let overflow slowly under the tap. ‘This way, all the mucus, foam, pieces of tissue and microplastics float out,’ says Leopold. These particles are caught in a sieve under the glass.

Ear bones

What Leopold is really interested in are the things at the bottom of the glass: the heavy ossicles (ear bones) of fish, called otoliths. Those bones provide information about the orca’s diet. ‘They are bones of half a millimetre to a one and a half centimetres in size. You can tell the species of the fish by their shape, and its size by their size.’

The first flush yields a meagre catch: one fragment of shell. We return to the tank. Now another bit of stomach emerges, which is dark and less folded. ‘This is the second stomach,’ says Leopold. ‘A whale has four stomachs. I don’t expect there will be any prey left in the second stomach, only liquid.’ The food enters stomach one, and stomach two produces digestive juices and releases them into stomach one. From there it goes back and forth and then the liquid matter flows on to stomachs three and four. ‘Those are more like outlets into the intestines.’

Metre by metre

After three flushes, the researchers are done with the stomach. The organs go into a red container in the freezing cell. The result: ‘Maybe one otolith,’ says Leopold, pointing to a white piece of bone in a glass petri dish. On to the gut. The researchers lay the slippery tube out zigzag on the table. ‘We want to measure the length of the intestine. That’s something we don’t know about the orca. The dissection table is exactly one metre wide.’ Leopold and Van Nierop count a total of 30.6 metres of intestine – which they also cut open and rinse, in search of ear bones. In vain.

It is clear that this orca wasn’t eating when she died

Leopold then examines the haul from the stomach under a microscope. What was assumed to be an otolith turns out to be a pebble. ‘Too bad,’ says Leopold. ‘So we can’t learn anything about the diet from this. Clearly, this orca was not eating when it died. If the diagnosis in Utrecht is starvation, we can at least confirm that.’ It is now 6 p.m. and the analysis is over. The door opens and the cleaner comes in. He glances around the room and asks Leopold: ‘Will you guys do the floor?’

Cause of death of Gala IB6

The next day (21 October), Utrecht University announced that the orca was diseased. She had a severe gum infection, and all her teeth were loose. She probably couldn’t eat because of the pain, hence the empty stomach. In addition, the animal had inflammation of a heart valve, the meninges, and the sexual organ. Muscle damage suggested that the animal eventually died due to the force of gravity on the beach.

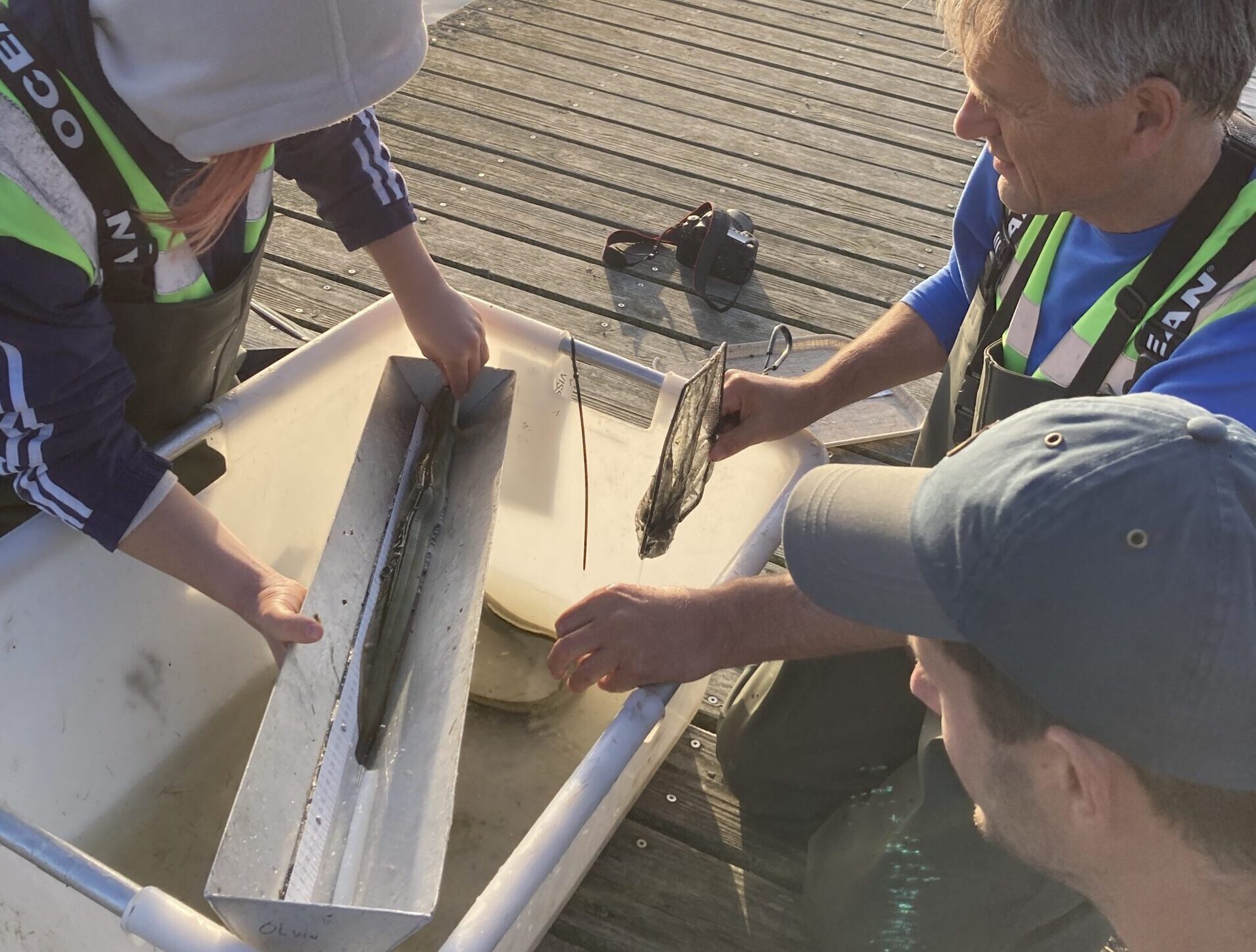

Leopold (left) and Van Nierop count a total of 30.6 metres of

intestine. Photo Stijn Schreven

Leopold (left) and Van Nierop count a total of 30.6 metres of

intestine. Photo Stijn Schreven