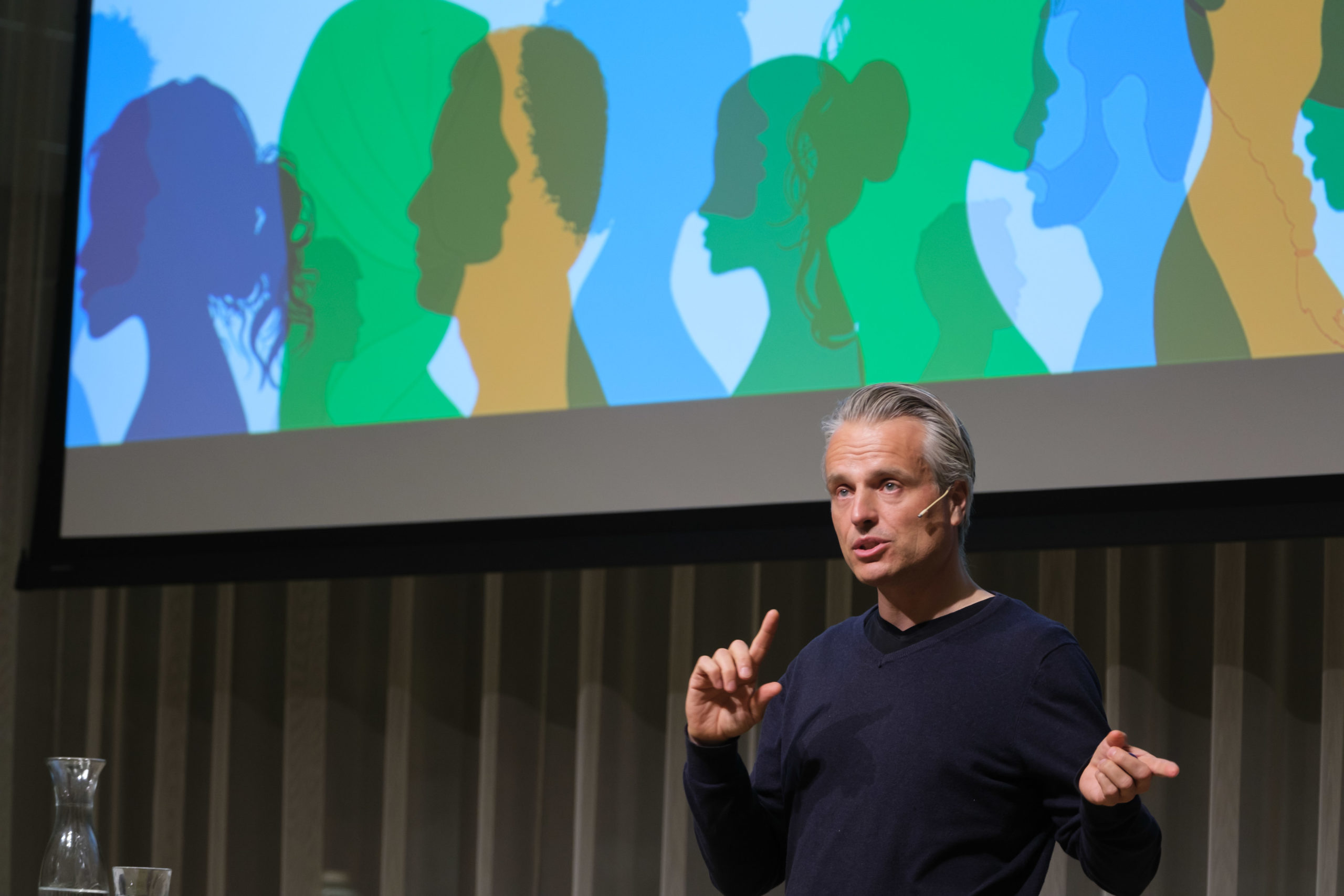

There was widespread outrage when journalist Joris Luyendijk published De zeven vinkjes (the seven ticks), his book on the seven dimensions of privilege. Once a popular speaker, now he did not even manage to fill the room at WUR. But he did stir up something.

Who does Joris Luyendijk think he is? Why should he of all people criticize privilege?! That was roughly the response to the publication of Luyendijk’s book on ‘how men like me get to be in charge’, in other words how privilege works. Half of his critics asked how Luyendijk had the nerve as a privileged white man to lay claim to ideas that so many less privileged people had tried to voice before him. The other half were furious that an ‘ordinary white man’ had become so woke he was attacking them — what had got into the man?

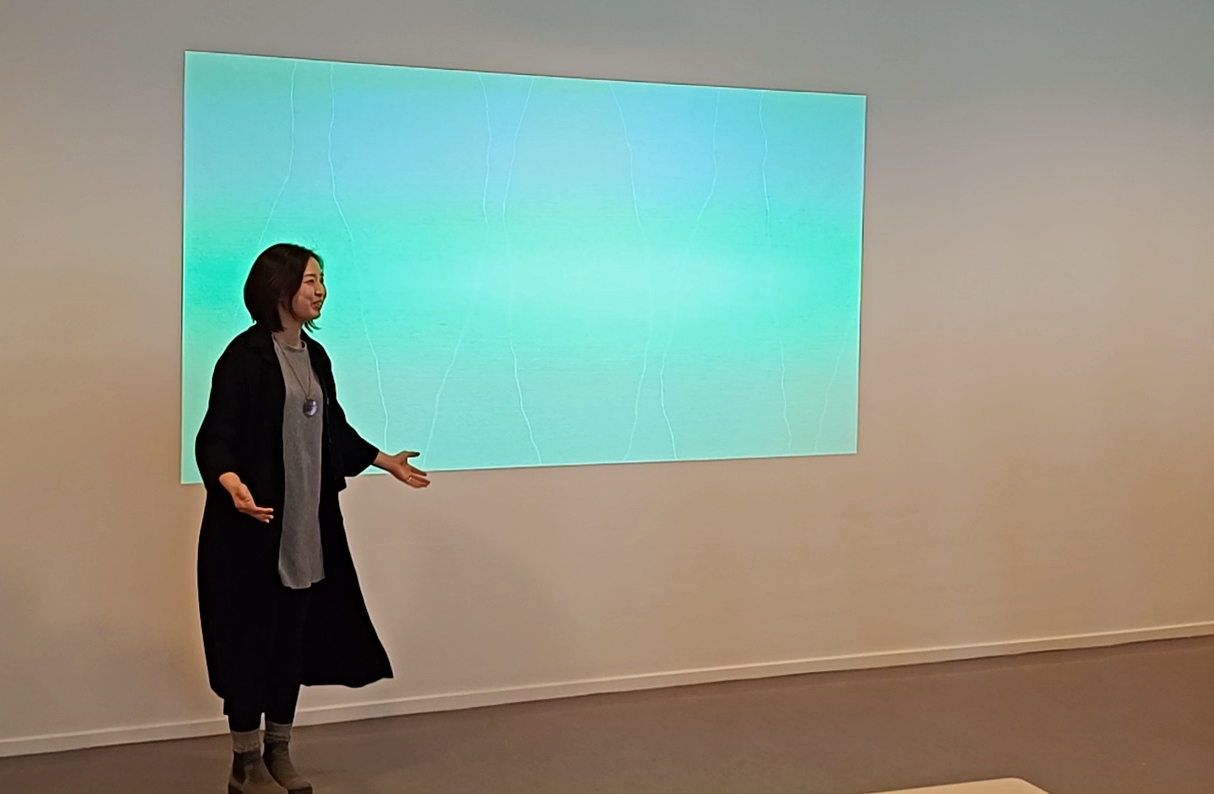

Not everyone at WUR was pleased either that he of all people was invited to speak during Diversity & Inclusion Week. Indeed, the room at Omnia was three-quarters full at best. But something did happen that evening.

Not when Luyendijk observed that the higher up you get in an organization, the more boring the hair styles and outfits. Nor when he gave some figures: that the Netherlands has as many people who are functionally illiterate as it does people with a university degree. And that statistically, the audience members should have at least two functionally illiterate people in their circle of friends. ‘But you don’t, do you?’

Zero ticks

And so Luyendijk continued with his sharp insights. For example, the uncomfortable truth that social class is incredibly important, even if we pretend otherwise. ‘Just ask people from working-class or farming families,’ said Luyendijk. ‘And ask the people who with an iron will have worked their way up through the educational hierarchy from lower technical school to university because the school system always recommended too low a level — rather than being overly ambitious like in my case. And the people in academia who are still underrated because they once attended a vocational university.’ He also mentioned university-going migrant children who get ignored by head-hunters because of ‘a lack of international experience’. ‘As if a life spent switching between cultures doesn’t count for more than six months on an exchange.’

Some people don’t tick any boxes

‘The world is designed by them, for them’ is how he summarized the position of power held by the men who tick seven boxes and the women who tick six. The implications were made really clear when Luyendijk got everyone in the room to stand and he then counted down: ‘Everyone with seven ticks, sit down. Now six ticks. Now five.’ He was planning to stop at one tick but then a woman — a WUR student — spoke up. ‘Some people don’t tick any of those boxes,’ she said. ‘I’m one of them. People have no idea how difficult that is, how many barriers you have to overcome.’ She gave a number of examples and turned to Luyendijk: ‘I’m so grateful that someone like you is addressing this issue. People listen to you, not to me. Everyone always says the Netherlands is so fair, open-minded and full of equal opportunities. But believe me, that is absolutely not the case if you don’t tick enough of those boxes.’

Photo Guy Ackermans

Photo Guy Ackermans