Potato professor Anton Haverkort has received a PhD for the second time in his life. On the potato, of course.

The red degree certificate tube is on the table: the latest bit of WUR history to be made in the historic building on the Wageningen canal. This was the hall of residence of the then Agricultural College in its early years. For several decades after that, classes were held here. ‘I was taught here myself,’ Haverkort recalls. ‘Agro-meteorology, taught by Professor Kees Stichter. And now I live here.’

The PhD certificate has only been here a day. It is Haverkort’s second. He obtained his first in 1985 at the University of Reading. What followed was a glittering career in the potato world – a career that ended on 9 December 2016, the day he turned 65. ‘Actually, I could have gone on for seven more months. But I always said I’d stop work at 65.’ Stopping work turns out to be a flexible concept.

Whereas most people slow down a bit after retirement, Haverkort, now an emeritus professor, went into overdrive. In 2018, that resulted in The Potato Handbook, a 600-page standard work on everything you ever wanted to know about the spud, but never dared to ask. The book is now available in English, Dutch and French, and a Spanish translation is on the way. For two years after that, Haverkort led the Climate Change Taskforce at a major potato-processing company. And now he’s produced a thesis. ‘But I’m taking a gap year next, mind you.’

No history

‘I intended to write a book on the history of potato processing, really. The Potato Handbook is about breeding, diseases, cultivation methods etcetera – basically about everything that happens before the potato reaches the processing plant.’ The scope of his initial goal proved too small: ‘You can’t fill a book with that.’ So Haverkort shifted his focus to all the stages of processing potatoes in the present day. ‘Everything from the harvesting on the farm to the processing in the factory, by the cook in the restaurant or the consumer at home.’

The book became a thesis, On Processing Potato, written under supervision from Han Wiskerke (Professor of Rural Sociology), Paul Struik (Professor of Crop Physiology) and Anita Linnemann (Food Quality and Design). The thesis is brimful of facts, trivia, tables and diagrams about the innumerable ways in which people process spuds into products and ingest them.

Haverkort’s method makes it possible to ask research questions about potato processing

A feat, for sure, but not science as such. Yet the thesis earns its scientific laurels because of the way Haverkort has arranged and analysed his material.

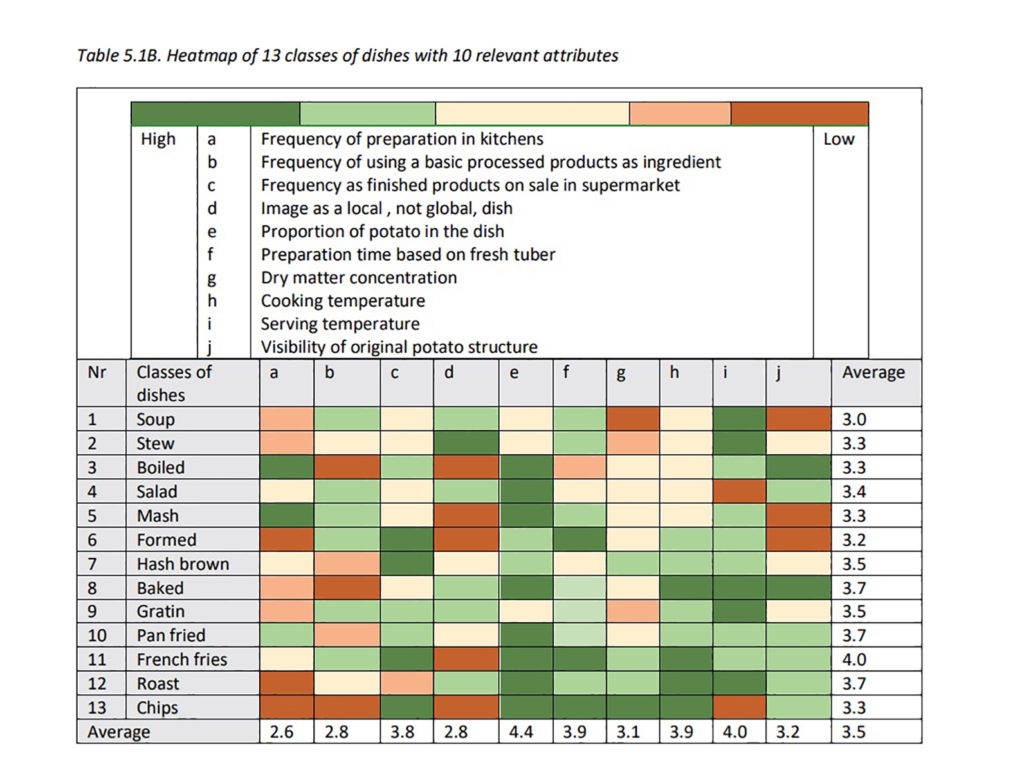

Getting to grips with the text takes time and attention. ‘Yes, my supervisors found it tough going too,’ laughs Haverkort. ‘You’ve got to concentrate. My writing style is not very straightforward and I tend to go into a lot of detail.’ But hey, here’s an attempt. Haverkort divides potato processing into domains with classes and properties. Haverkort: ‘Take the domain of the factory and all the processes that go on there, such as washing, peeling, etcetera. Those are classes of processes, of which I have identified 66. And all those processes have properties, such as the duration of the treatment or the temperature or pressure under which it takes place.’ Haverkort then assigns numbers and colours (from 1-red to 5-green) for the extent to which a property applies to an operation. ‘Temperature, for example, scores low for washing or peeling, but high for baking or roasting.’

Maths

‘My innovation is that I give a weight (grade) to all these properties, for each process,’ Haverkort explains. ‘This makes the qualitative description of all those processes quantitative and you can do maths on them, make heatmaps and cluster things in dendrograms.’ That method, according to Haverkort, makes it possible to answer research questions, for example about process efficiency, energy use or waste production. Haverkort’s system resembles the way Linnaeus imposed order on nature. Whether his method will become as widely used remains to be seen. ‘I hope so,’ he says. ‘But you never know. These things take time. I probably won’t live to see it.’

Haverkort is more confident about the future of the potato itself, which is bright. Ever since the Spanish brought the tuber to Europe from South America, the spud has risen in the world unstoppably. Based on fresh weight, it is the world’s third staple food crop after wheat and rice. And the prospects are good. Indeed, the potato is benefiting from climate change, which means that cooler northern regions like Sweden, northern Siberia and Canada are becoming suitable for growing potatoes, according to Haverkort.

At present, potato farming still suffers a lot from the notorious disease phytophthora. But that, according to Haverkort, is only a matter of time. ‘There is no need for potato plants to get diseased. We know what to do to get resistance to phytophthora.’ He himself was closely involved in developing it. There is one ‘but’, though: that resistance is obtained through genetic manipulation and is therefore bound by rules. ‘But if those breeding techniques are approved shortly, the potato will become an even more important crop.’

Anton Haverkort. Photo: Guy Ackermans.

Anton Haverkort. Photo: Guy Ackermans.