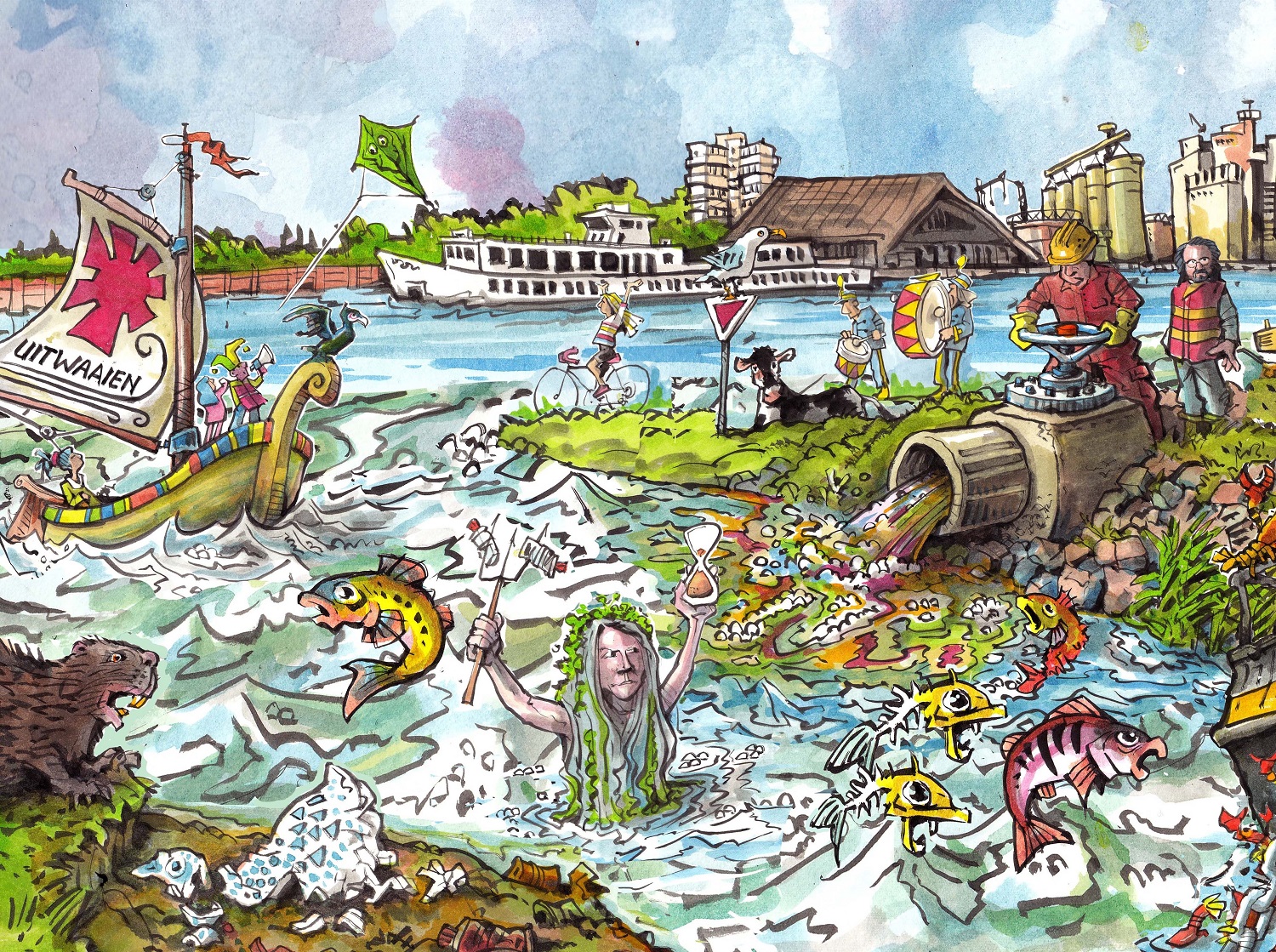

The Rhine was once the European sturgeon’s preferred spawning ground. And that time will come back, if it’s up to PhD student Niels Brevé. Through the sturgeon, he is paving the way for the ecological recovery of the river.

If you want to see Acipenser sturio in this country, you have to go to Rotterdam’s Blijdorp Zoo, where there are sturgeon of about one and a half metres long in the aquarium. Little ones, says Niels Brevé dryly. And he should know. For his doctoral thesis on the reintroduction of the sturgeon to the rivers of north-western Europe, he comprehensively documented the historical distribution of the beast.

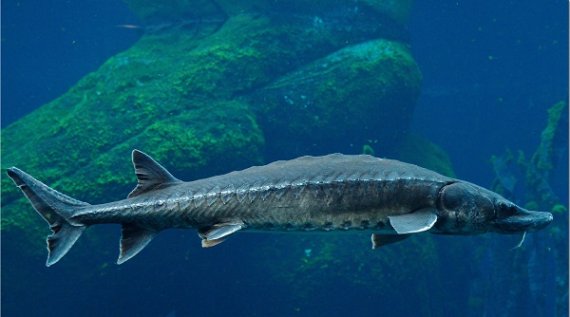

And beast is the right word here. ‘The sturgeon is actually megafauna,’ says Brevé. ‘Like the elephant. It’s the biggest freshwater fish we know. They can easily reach three metres and, in exceptional cases, even a few metres longer.

The largest I’ve encountered was five metres long and weighed 350 kilograms.’ That monster, by the way, was caught in 1869 by Belgian fishermen at sea, which is the sturgeon’s real home.

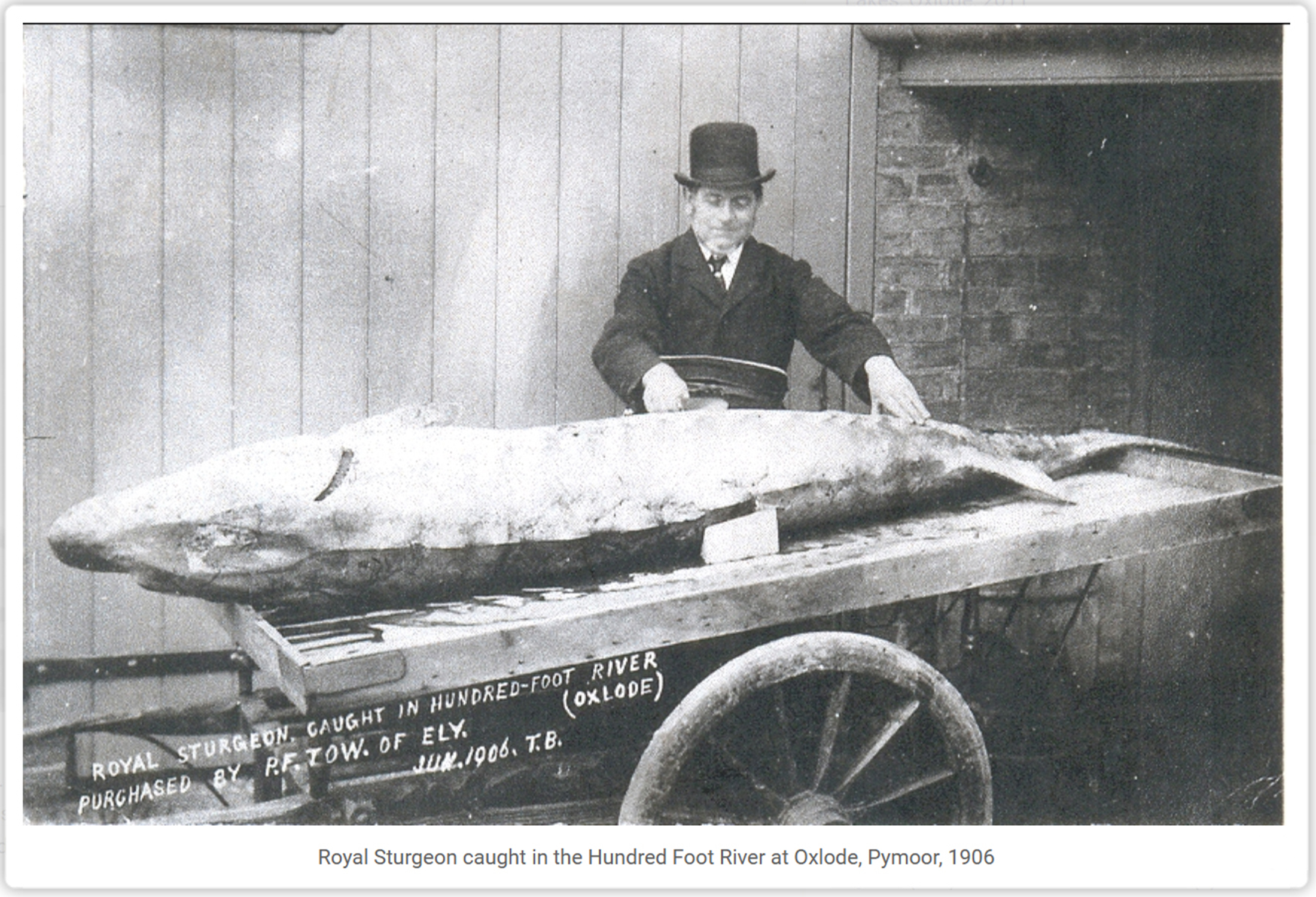

Brevé’s inventory includes many fish of similarly monstrous proportions. The heaviest, a specimen found in July 1928 in the Rhine near Rees, in Germany, weighed 375 pounds. You can’t catch these girls – the extremely large ones are always females – with a fishing rod. At that time, the sturgeon had already been in decline for a while. The last time a sturgeon was caught in the Dutch reaches of the Rhine was in 1952. The last sturgeon recorded in the IJsselmeer bay was caught in 1960.

Spectacular

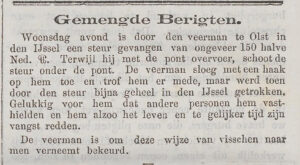

At one time, thousands of sturgeon must have swum in the Rhine and waters linked to it, Brevé thinks. ‘But we don’t know.’ What he does know about numbers is based mostly on newspaper articles. Brevé and historian Rob Lenders (Radboud University Nijmegen) pulled out all the stops to reconstruct the sturgeon’s distribution since the 14th century in the rivers of the Netherlands, Germany, Belgium and France. This resulted in more than 5000 records of more than 40,000 sturgeon. ‘A life’s work’, is his own description of this painstaking work. ‘I’m glad it’s finished.’

That so much has been written about the sturgeon is partly due to its spectacular size.

The sturgeon is the biggest freshwater fish we know

Brevé: ‘There was a time when fishermen would travel from town to town with the fish and charge people to see them. The fish would stay fresh for a week or two, and then it could be sold for consumption. That would depend on the degree of scarcity, of course. Around 1850, an adult sturgeon was worth 1000 euros. In 1920, it was worth twice that, in today’s terms.’

That catches were reported was also due to the requirement to register them. The sturgeon was a fish on which the owners of the fishing waters charged tax. Brevé: ‘Owners of fishing waters such as the Count of Holland and the Bishop of Utrecht demanded payment for all fish caught in the Biesbosch (a network of waterways, ed.).

The Rhine is completely open to shipping, and therefore to fish too

In those days there were about 20 leaseholders; large royal companies that fished for salmon, allis shad and sturgeon. A tax inspector checked that all fish were registered. In the second half of the 19th century up to 100,000 salmon and 200 to 600 sturgeon were caught annually.

Little of that tax registration has survived, however, which is why Brevé delved into old newspapers, manuscripts and fisheries documentation. ‘The more recent they were, the more data they delivered. Until 1930, that is, by which time the sturgeon had all but disappeared.’ The sturgeon was wiped out by overfishing in the North Sea with steam trawlers, pollution and damage to its spawning and nursery grounds.

Salt and fresh water

There are lessons to be learned from the historical overview. Maps made by Brevé show clearly where the catches were made, and thus where the fish were located. ‘If you want to bring back the sturgeon, you have to focus on the lower reaches of the Rhine,’ says Brevé. ‘That means the Haringvliet estuary, the Biesbosch and the current port of Rotterdam, where the fish gathered to acclimatize to the transition from salt to fresh water. And the spawning grounds and nurseries upstream towards Germany.

Knowledge about the sturgeon is mainly based on newspaper articles

If we want to tackle the recovery of the sturgeon, we should start in the Netherlands and move on to Germany.’

The fact is that spawning (reproduction) is the only reason the sturgeon leaves the open sea for the narrow rivers. The sturgeon is anadromous, Brevé explains. ‘That means that it can live in both salt and fresh water. But it is primarily a sea creature. That’s where most of its food is and where it grows up. Adults swim upriver to spawn, and then they return to the sea. To spawn, they need oxygen-rich gravel beds. And those are found mainly in the Rhine.’

The preference for gravel is due to the vulnerability of the eggs and larvae. ‘Gravel is coarse-grained and offers protection. As soon as the roe is spawned, the eggs become sticky and attach themselves to hard substrate. They hatch out as very fragile yolk-sac larvae that need to be able to hide in the gravel or they will be devoured in no time. After about a year, the young sturgeon are strong enough to swim to sea.’

Released

Brevé feels sure that there is a future for sturgeon in the Rhine, and there is experimental evidence for his conviction. It is not entirely true that sturgeon have not swum in the Rhine since 1952. Brevé helped release them himself, first in 2012 and again in 2015. Three- to five-year-old tagged sturgeon of one metre in length were released into the Rhine on the border of the Netherlands and Germany, to see whether and how they could find their way to the sea. Most of the sturgeon passed the test with flying colours.

The next phase of the project may take place this year: the release of tagged young sturgeon. With money from the Post Code Lottery and in cooperation with ARK Natuurontwikkeling, the World Wildlife Fund and the French, German and Dutch governments, the Dutch angling association Sportvisserij Nederland (Brevé’s employer) is going to release 700 young sturgeon at known spawning grounds.

It will take a long time, however, before the sturgeon will spawn again in the Rhine. The sturgeon has a long life cycle and can live for over 100 years. Brevé: ‘Males only spawn after 10 to 12 years, females after 15 to 22 years. So you really need a lot of patience with these fish. And a lot of money, but we’ve got to be willing to pay the price.

Around 1850, a sturgeon was worth 1000 euros

We have all invested billions of euros in making the Rhine the artery of our economy. And a clean and healthy Rhine is worth a lot too.’

Meanwhile, sturgeon are being spotted occasionally at sea too. ‘In the last five years, there have been 28 reports of sturgeon of nearly two metres in length,’ says Brevé. ‘These are fish that have been released into the Elbe in Germany and the Garonne in France. They end up in fishing nets in the North Sea. They survive that if they are handled properly and put back. These are strong, sturdy fish.’

With a bit of luck, Brevé will witness sturgeon spawning in the Rhine again in his time. His study suggests that if it can be done anywhere, it can be done there. ‘The Rhine is one of the few rivers that is completely accessible to shipping. And therefore to fish too: 850 kilometres from the mouth at Rotterdam to Iffezheim. Various migratory fish are slowly returning. Salmon, houting and sea lamprey preceded the sturgeon. They will never reach the numbers of the past, but they are coming.’

Niels Brevé (1966)

Birthplace: Amsterdam

Place of residence: Wijk bij Duurstede

Degree: Geoscience VU University Amsterdam

Work: Senior project leader at Sportvisserij Nederland in Bilthoven.

Research: The migratory behaviour of sharks and rays in the North Sea, using transmitters.

Also: a part-time PhD candidate at Marine Animal Ecology and Aquaculture & Fisheries.

There was a time when fishermen would travel from town to town with the fish and charge people to see them.

There was a time when fishermen would travel from town to town with the fish and charge people to see them. ![[Seriously?] New year swim postponed until July](https://www.resource-online.nl/app/uploads/2024/01/WEB_De-neus.png)