The oldest tomato in the world can be found in the basement of Naturalis natural history museum, shows a study by botanist Tinde van Andel and her right-hand person Anastasia Stefanaki.

So there it is, the En Tibi. One of the oldest herbarium books in the world. Supported by two cushions, on a trolley in the catacombs of Naturalis natural history museum in Leiden. And this reporter is allowed to pick it up and hold it. Just like the scholar and book collector Isaac Vossius did in Stockholm, when he was a librarian indexing the Swedish queen Christina’s treasury. As did Christina herself when she received the book as war booty at the end of the Thirty Years’ War. As did the Habsburg Emperor Rudolph II in Prague, in whose treasury it once lay. And his grandfather Emperor Ferdinand I, the probable patron of the masterpiece.

Herbarium

to Leiden University in 1690

And of course, as did the Italian botanist Francesco Petrollini, who made the herbarium in 1558. We know this since Anastasia Stefanaki (Biosystematics, WUR) conducted an extensive study of the contents and origin of the book. She not only identified the 500 dried plants in it, but after a meticulous study done with a team of specialists, she came to the conclusion that the creator of the famous herbarium must have been Petrollini. That put an end to a previous assumption that the En Tibi was the oldest herbarium in the world to include a tomato plant. Thanks to Stefanaki’s research, we now know that honour belongs to a herbarium by Petrollini’s contemporary and colleague Ulisse Aldrovandi. In 1551, he started a herbarium that would eventually fill 16 (!) volumes and include no fewer than 4000 plants. The tomato plant is in the first volume.

Dried

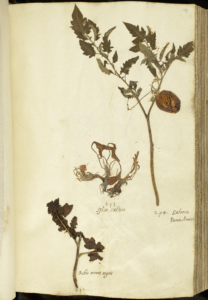

‘The two books are seven years apart. But it’s not a competition, is it?’ is Stefanaki’s laconic comment on that second place. And after all, the En Tibi (Latin: ‘Here for you’) is special enough in itself. It contains the oldest tomato plant with a ripe fruit. Dried, of course, but still. There, that’s the one! The little plant is halfway through the book, labelled number 294. Salunca Puma Amoris, it says. The colours have faded slightly over the past half millennium. But the red is still clearly visible.

The tomato is in 2D. How is that possible? ‘Petrollini peeled the skin off the tomato and put it in the book in a round shape so that it looked just like a real tomato,’ explains Tinde van Andel, special professor of Ethnobotany. It is not known exactly how the botanist did this, but the dried tomato is certainly unusual. ‘None of the other herbaria from that time have one, or only unripe or very small ones. Or botanists painted one in. This is a really good tomato.’

Rooted art

The En Tibi’s full name is En Tibi perpetuis ridentem floribus hortem. In other words: ‘For You, an eternally smiling flower garden’. The 16th century herbarium is one of the top pieces from the Naturalis collection. Queen Christina gave it in payment to Vossius, who sold it – together with several thousand other books – to Leiden University in 1690. The university gave it to the Leiden Herbarium, which was merged with Naturalis in 2009. ‘Actually, it is looted art,’ Van Andel remarks dryly. ‘Not by the Dutch, but by the Swedish bibliophile Queen Christina, who got it as war booty.’

Van Andel calls the En Tibi a ‘masterpiece of art and science’. But its contents and history have long been kept obscure. That is not uncommon, she says. ‘The more you have in your house and the more valuable it is, the stronger the locks on our doors need to be.’ This is one of the difficulties she encounters in her work. Administrators are careful with their treasures. ‘Only after digitization was it possible to study the book properly,’ Stefanaki adds. ‘That determination of the plants was in fact the first step towards finding out where the book came from.’ The digitization took place on the initiative of Van Andel and the then-new collection manager of Naturalis in 2009. ‘We thought it was a shame that the book was just lying around in the warehouse and nobody was looking at it. The digitization was a costly undertaking, though. These are not flat sheets that you can scan quickly. And the book is fragile and has to lie on cushions. A whole cage was built around it in order to take the photos. Cost: Six euros per page. At the same time, we engaged Anastasia to identify the plants. She is Greek and knows the Mediterranean flora. But believe me, it was quite a tough job. There are 500 of them and not all of them are clearly recognisable.’

Dan Brown

The research into the origins of En Tibi led to a follow-up study on the arrival of the tomato in Europe. Van Andel: ‘Anastasia had discovered that the maker of the En Tibi had made an even older herbarium with a tomato plant. So ours was not the oldest. She had also looked for various illustrations from that time. Then Covid hit and suddenly we had nothing in our diaries. So I was crazy enough to say: come on, let’s look into this properly. And that got totally out of hand, because it is incredibly complicated.’

It got completely out of hand, it’s incredibly complicated

WAnyone who imagines this detective work to be some kind of Dan Brown-like tour of old libraries is in for a disappointment. Most of the research is done online and at a desk. That is, if books have already been digitized. Van Andel: ‘Sometimes books have been photographed, but then they are not always online. Sometimes they have not even been photographed and you have to ask for a high-res photo. Or there are drawings, but there are 500 of them and you just have to search through them to find out which one is the tomato. It was a huge quest.’

It was a huge quest

The search eventually resulted in an overview of eight surviving 16th century herbaria with a tomato plant, various descriptions of the new plant and 13 illustrations from that time. These show the enormous diversity of tomato plants that were brought to Europe from the New World. ‘There were a lot of different varieties,’ says Van Andel. ‘Some were long and ribbed, others more like small bulbs. There was a great diversity of shapes and colours.’ And perhaps even greater than we realized up to now. ‘You can only look up the published drawings by famous botanists. All the scribblers just below that level have fallen into oblivion. Their work is stored anonymously in libraries and gets forgotten.’

Drying process

Nevertheless, Stefaniki thinks you are unlikely to find any tomato plants or illustrations of tomatoes that are even older than these. ‘These were the first herbaria books ever made. They mark the beginning of botany as a distinct science. These people were the first to go out into nature and collect plants, dry them and glue them into books.’ Van Andel adds: ‘They are also all botanists who knew each other and were in the same class. Their teacher was Luca Ghini, who taught botany in Pisa. He discovered the drying process. Those tomato plants probably all come from the same gardens in Florence, Bologna and Pisa. By the way, we know of other students of Ghini who made herbaria, but their books have sunk without trace. Perhaps they will be discovered one day.’

These were the first herbaria books ever made

Love apple?

The tomato in the En Tibi is labelled Salunca Puma Amoris. That is a mistake. Salunca is the name of the other plant on the same page. Nor is the tomato a ‘love apple’. According to Van Andel, the plant was confused with the aubergine (Pomes da Mouri) that was brought from Asia by the Moors. The corruption into ‘love apple’ is thought to refer to the supposed aphrodisiac properties of the tomato. The name ‘tomato’ is actually derived from Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. They call the plant tomatl.

Tinde van Andel (left) and Anastasia Stefanaki carried out in-depth investigations into the content and

origins of the En Tibi. Photo: Roelof Kleis

Tinde van Andel (left) and Anastasia Stefanaki carried out in-depth investigations into the content and

origins of the En Tibi. Photo: Roelof Kleis