Bacteria and fungi compete for food and, in doing so, develop their own weapons: antibiotics. We use these substances to combat pathogenic bacteria in humans. An increasing number of bacteria are becoming resistant, however. PhD candidate Barbara Terlouw uses computer technology to search for new antibiotics in bacterial DNA.

‘Proteins are the worker ants, the machines, in every living cell’, says Barbara Terlouw (Bioinformatics). ‘So bacteria that produce antibiotics contain proteins that build the antibiotics.’ She studies the DNA of bacteria to discover new antibiotics. The proteins are “mini weapons factories”. ‘You might consider a protein as a long production line, along which different parts of the protein each add a piece to the antibiotic they build together. The proteins I am working on are the coolest there are.’ Barbara Terlouw was awarded the Storm-van der Chijs Grant for her research, along with co-winner Katherine Barragán-Fonseca.

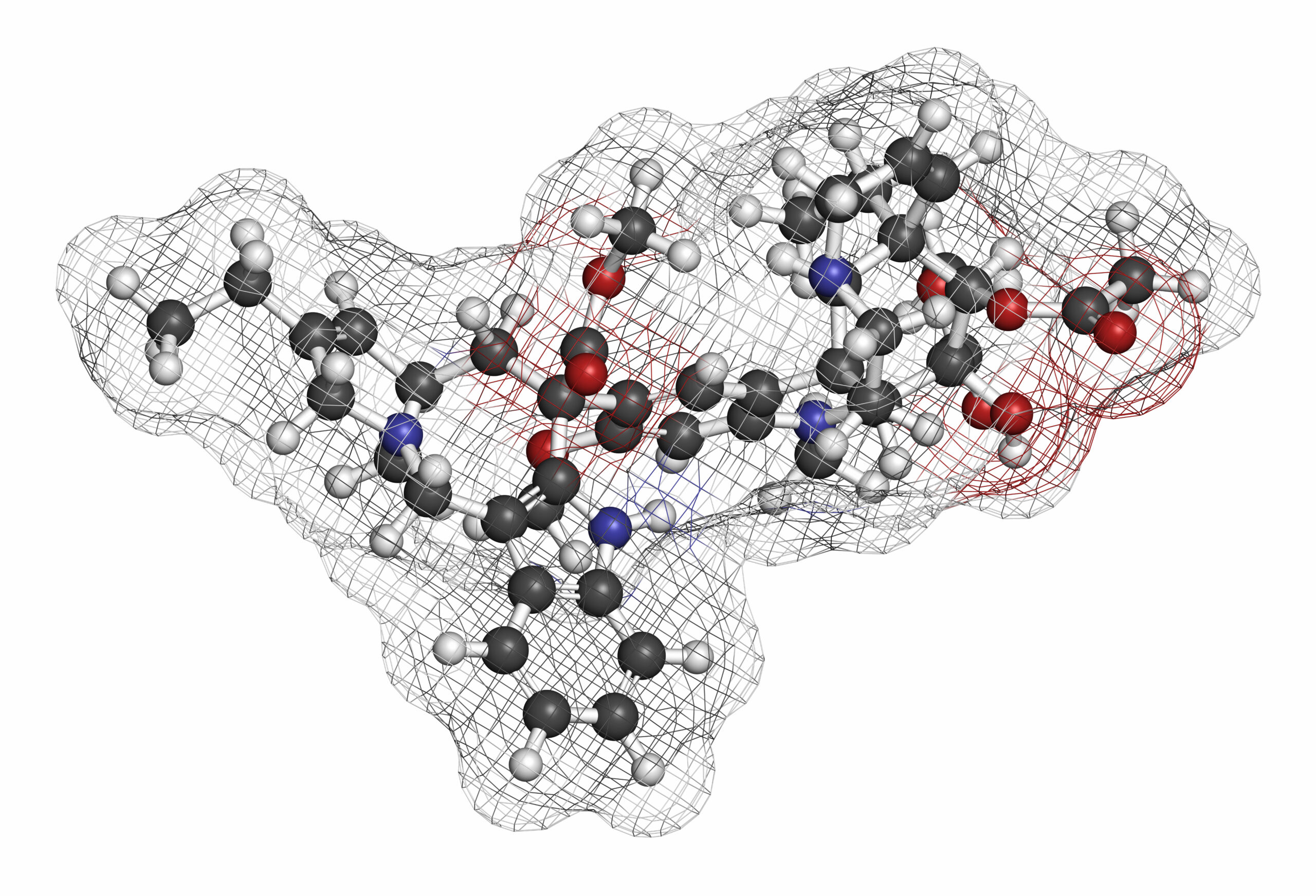

This protein consists of multiple links (modules), each of which adds a building block in three stages. ‘Each step is carried out by a different part (domain) within the module. One domain recognises the piece that needs to be added, the second sticks the pieces together, and the third has a gripper arm with which to pass the construction kit on to the next link.’

Terra incognita

Terlouw’s research is part of the overarching NACTAR project under the Dutch Research Council NWO. This project explores eight strategies to combat pathogenic and resistant bacteria. Her main focus is on Actinobacteria, a group of bacteria characterised by the enormous diversity in substances they produce. Two-thirds of the antibiotics that are currently used originated from this bacteria group, for example the substance daptomycin.

Modern technologies show that these bacteria are capable of much more than we currently know. The researcher strives to explore this uncharted world. During a visit to the University of Warwick, she characterised two protein domains that produce antibiotics. ‘Depending on what the protein domain looks like, you can predict what piece of the puzzle they add.’

Machine learning

Terlouw applied her laboratory research to computer analyses. ‘I analyse large databases of DNA codes to determine what pieces of the puzzle a protein domain adds to the antibiotic. With thousands of examples, you can subsequently train self-learning computers to predict these pieces for each protein domain. I wrote a machine learning tool that does precisely this.’

Next, she adds chemistry. ‘We used computers to predict the building blocks. Now, the question is how they stick together.’ The ultimate goal is to use DNA codes to predict what undiscovered antibiotics a particular bacterium is capable of making.

Talented

The Storm-van der Chijs award is a prize to encourage female PhD candidates to pursue their scientific careers. The 1500-euro grant will enable Terlouw to participate in two conferences in Denmark and Edinburgh within her domain: the discovery of natural products made by microbes.

Daptomycin: an antibiotic produced by Actinobacteria. Photo Shutterstock

Daptomycin: an antibiotic produced by Actinobacteria. Photo Shutterstock