Sterrin Smalbrugge does doctoral research at Wildlife Ecology and Conservation, writes books, gives educational performances, presents the Videoland programme Reptielengek! (Reptile-mad!) and took part in Expedition Robinson. Where does she get her drive from?

Smalbrugge’s life reads like a fairy tale: from introvert researcher to media celebrity. She lives with her boyfriend in a shepherd’s hut in Spain, which she has made a safe haven for animals. And it all started with a love of scaly crawling creatures.

Why reptiles?

‘Reptiles are endlessly fascinating. They have adapted to their habitat in so many different parts of the world in the most brilliant ways. A nice example is the spider-tailed viper, which lives in a mountain range in Iran where few animals can survive. At the end of its tail hangs something that looks and moves like a spider, which it lures birds with. They think they’ve found a tasty snack, but it turns out they are the snack. How clever is that?

Or look at the way the crocodile can bite a zebra in half with its jaw, and with the same jaw can gently transport its babies. Or the evolution of poison, and the fact that humans can use that poison as medicine.

What is more, reptiles play crucial roles in ecosystems, for example in pollination, seed dispersal and water purification. And they do it for free! That’s why we must respect, appreciate and protect reptiles.’

It is your ‘Life’s mission to make the world a better place for undervalued animals, especially reptiles’. How are you doing that?

‘I’m doing it with two tools: science and education. There are more than 11,000 species of reptile and that makes this group of animals more diverse than birds or mammals. And yet much less research is done on reptiles. When fundamental knowledge is lacking, how can you possibly establish an adequate conservation plan? Biodiversity is crucial to saving the world, but there is one whole animal group that we tend to forget. I want to expand that body of knowledge with my research.

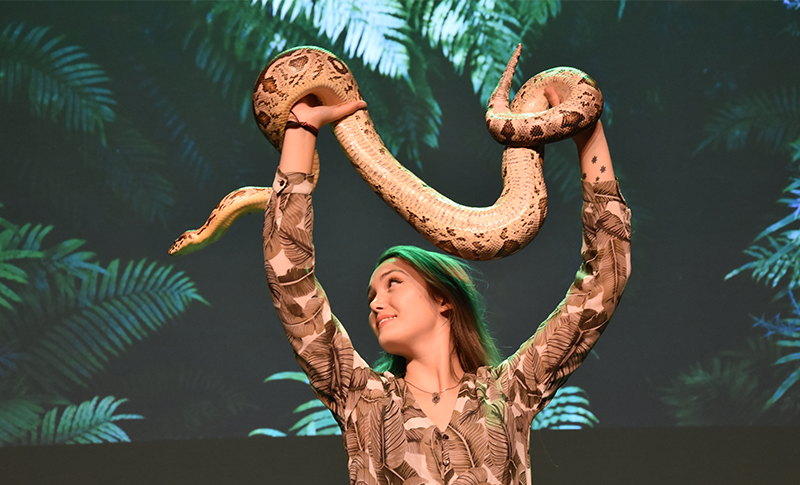

I also use education to improve the public image of these animals, with things like theatre performances, the TV programme Reptielengek!, my work for National Geographic Junior, and by writing children’s books. I want the young generation to see how amazing this animal group is, so that the nature conservationists, scientists and animal caretakers of the future will focus on reptiles and not just on birds and mammals as they have in the past.’

Why is it important for public opinion about reptiles to improve?

‘It makes it easier to get funding for scientific research on reptiles and to protect them. Take lions, for example: they have soft fur and beautiful manes. They are on posters in children’s bedrooms. When someone shot the popular lion Cecil in Zimbabwe in 2015, that person received death threats and had to go into hiding. But if 300 crocodiles are slaughtered somewhere because a villager was attacked, no one says a word. Everywhere I go, people chop off black mambas’ heads. It is sheer discrimination: because reptiles have scales instead of strokable fur, they apparently don’t deserve the same attention. My big hero Steven Irwin said, “Humans want to save things that they love”. So if you want to protect reptiles, you’d better make people start loving them.’

If you want to protect reptiles, you’d better make people love them

WUR doesn’t have a degree programme that focusses on reptiles. So what made you decide to study here?

‘I didn’t want to be just a number at a big university and at Wageningen there was scope for your own interests and development. Ecology was a logical choice, because it teaches you to really look at interactions in nature. I have spent hours talking about zoology with Arie Terlouw – one of my favourite teachers at WUR. He can enthral an audience with his stories about it. At one point he said, “You’ve got so much to tell people about reptiles, let’s start sharing that!” So then I gave several lectures, while still a student myself. First, about the king cobra, and then about reptile superheroes. That drew the national media’s attention, which set the ball rolling, and I started to do educative theatre performances. Later, when I was doing my Master’s in Forest and Nature Management, I met Art Rooijakkers (a well-known TV presenter, ed.). He helped me find my way around the media world and through him I ended up with National Geographic Junior and Videoland, with my show Reptielengek!’

You took part in Expedition Robinson. What was that like?

‘You’ve got to survive under primitive conditions, with people who are very different to you. So you need to let down your guard and cooperate. You learn a lot about people and about yourself: it’s a kind of pressure cooker for life lessons. I always thought I couldn’t get on very well with people because I’m shy and an introvert. That might sound strange given that I seek attention in all sorts of ways. But I need an audience to fulfil my mission. In spite of my shyness, it turns out I can get on well with people. Non-human animals are still my favourites, but I have rediscovered the beauty of humans.’

You are doing doctoral research on the ecological trap hypothesis. What is that?

‘It’s about the indirect influence of people on animals. People are constantly making changes to the habitat. Unnatural habitats can look more attractive to animals than their natural habitat. If they then start making disproportional use of them, leading to lower survival or reproduction rates, that is called an ecological trap.

I am looking at that in relation to the influence of water structures on toads in Spain. One of my ideas is that water storage tanks amplify or distort the mating calls of toads. That makes other toads think: hey, there’s a party over there! Then they fall into the tank and fewer of them survive.’

How are you experiencing the Covid period?

‘The pandemic is affecting every aspect of my life. Theatre shows have been postponed up to seven times, so I’ve lost a lot of earnings. And it’s very sad to get messages from young fans who were looking forward to my shows. I try to compensate for that by sending them cards and video messages. Due to travel restrictions, we couldn’t do the filming for programmes either.

I focus as much as I can on what is possible, such as my work for National Geographic, and writing books. My first adult book comes out at the end of May. It’s about reptiles too. I get hope from my contact with followers and fans. But my love of nature is my biggest anchor. My boyfriend and I live in Spain, in a shepherd’s hut high on a mountain in the Sierra Nevada National Park – one of the most beautiful nature areas in all Europe. We are trying to make it a safe haven for all animals. We’ve made a rabbit warren there, hung up nesting boxes for bats and birds, and dug an amphibian pond where threatened species of amphibians can breed too. A wild snake recently moved in, which I often see when I’m doing laundry. And ibexes pass through our back garden.

A wild snake moved in, which I see when I’m doing laundry

More and more people from our area know about us now. I recently got a phone call from the electrician, who had found a snake. Normally he would have chopped off its head, but he had heard about what we are doing, so we could save the snake. That way, an attitude changes that is as old as time itself, which is a wonderful thing to see.’

Sterrin Smalbrugge (1993) is doing her PhD in the Wildlife Ecology and Conservation chair group, made the Videoland programme Reptielengek (2019), is an ambassador for National Geographic Junior, has written several children’s books and performs in educational live shows. Her first book for adults about reptiles will be published in May 2022.

‘In my shows I try to show the young generation how special this class of animals is, in the hope that future nature conservationists, scientists and animal keepers will also focus on reptiles.’ Photo: Sterrinswildworld

‘In my shows I try to show the young generation how special this class of animals is, in the hope that future nature conservationists, scientists and animal keepers will also focus on reptiles.’ Photo: Sterrinswildworld