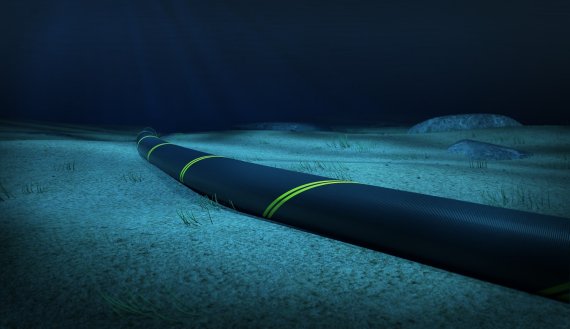

Do the power cables of the wind turbine parks in the North Sea hinder sharks and stingrays? A WUR-led consortium funded by the NWO is finding out.

Sharks and rays can ‘see’ electromagnetic fields. They make use of this ability to hunt and possibly even to navigate. The power cables of marine wind turbine parks could prove a hindrance. But, how great is the effect of the electromagnetic fields surrounding these cables on marine life? This is a yet unanswered question. Professor of Marine Animal Ecology Tinka Murk leads an investigation to find answers.

ElasmoPower

The project, mainly funded by the NWO (Dutch Research Council) is called ElasmoPower, referring to the elasmobranch fish (sharks and rays) on which the research focusses. Currently, sharks and rays seldomly visit the (Dutch part of) the North Sea. ‘And even then, just the smaller species such as the thornback ray. But we hope they will return in, among other areas, the wind turbine parks’, says Murk, ‘where the habitat is actively recovering, and no fishery takes place.’

Animals swimming in coastal areas, may see it as a Himalaya of electromagnetic fields

Tinka Murk

Power cables could present a problem. Murk: ‘The number of power cables and the amount of power transported to land is increasing dramatically, and with it, the exposure of animals to electromagnetic fields. A preliminary study showed that the field reaches as far as 25 meters on either side of the cable. Animals swimming in coastal areas may see it as a Himalaya of electromagnetic fields, which could cause them to alter their course.’

A study involving eels with transmitters shows they slow down when near cables, Murk explains. Shark bites have been found in cables in the ocean. ‘It is not clear whether this is aggressive behaviour, or whether the electromagnetic fields cause them to consider the cables prey. We don’t yet know what the effects are exactly, nor what field strengths affect sharks and rays.’

Cameras

‘Finding a relationship between field strength and animal behaviour is the first step’, Murk clarifies. ‘And not just in mature animals, but also in unhatched eggs.’ At a later stage in the five-year investigation, field studies will be conducted on artificial riffs both near and far from power cables. ‘We will monitor animal behaviour with the help of cameras and sensors. And with the help of molecular techniques, we will see if the cables influence the composition of communities.’

WUR conducts this research in collaboration with a large number of partners, including grid operator TenneT, Naturalis, the Noordzee foundation and engineering office Witteveen + Bos. The latter has also provided a PhD candidate, Annemiek Hermans, who will be working on the project for three days a week. The entire project will cost 1.2 million euros.

Photo: Shutterstock.

Photo: Shutterstock.