Foto’s: Rolf Bak, Didier de Bakker en Erik Meesters

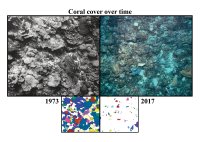

Didier de Bakker defended his thesis on the changes to the reef around the Caribbean islands of Curaçao and Bonaire on 17 April. The core of the study, which he conducted in the Aquatic Ecology and Water Quality Management chair group, is a unique set of photos of the reef. The first of these photos were taken in 1973 by the now retired University of Amsterdam professor Rolf Bak. He photographed 16 sections of reef three by three metres in size, at depths of 10, 20, 30 and 40 metres off the coasts of Curaçao and Bonaire. Since then, these quadrants have been photographed almost annually up to the present day. The series is a scientific gold mine, says De Bakker. Although the picture it paints is not a cheering one. ‘When Bak started, the reef still looked healthy. Deterioration has set in since then.’

Slimy mats of bacteria

De Bakker has described in detail which species of corals can be seen on the photos and then charts the changes it has undergone over the past 40 years. His analysis shows that three quarters of the coral cover has disappeared since 1973. The coral has made way for turf algae, macroalgae and cyanobacteria. ‘The shift from coral to algae is a much-studied phenomenon,’ says De Bakker. ‘But the rise of cyanobacteria is new and striking. Slimy mats of reddish brown cyanobacteria are slowly taking over.’

Their scientific article about this in 2017 won de Bakker and his co-authors the prize for the best article about coral reefs from the academic journal Coral Reefs. The cyanobacterial mat had literally been overlooked until then. Understandably, says de Bakker. ‘The focus always lies on corals and microalgae. Thanks to my inventory, I focused on the full range of species present. And I could not fail to be struck by how often I came across those cyanobacteria. Another factor is that red is the first colour to disappear from the spectrum under water. And the green-brown mass you then see has long been assumed to consist of turf algae.’

Besides the massive loss of coral, the composition of the remaining species changed dramatically as well. De Bakker: ‘Traditionally dominant species such as Acropora and Orbicella have largely disappeared, or are struggling. These true reef-builders, which lay down chalk fast and form large colonies, are making way for fast-growing species that calcify much less and do not build large colonies.’ So the formation of new reef is slowing down, while the breakdown of existing reef is increasing. De Bakker: ‘The red boring sponges do an awful lot of damage. They bore a hole in the coral, push their way in and devour the contents of the skeleton from the inside. They erode the chalk with acid and actively loosen and remove bits of it. This causes the reef to lose its 3D structure extra fast.’

Pollution and warming

The reasons for the severe degradation of the coral reef are known – deteriorating water quality, over-fishing and the warming up of the sea. ‘Pollution brings nutrients into the water,’ explains de Bakker. ‘That is good news for algae and other organisms that can grow faster if there are more nutrients. But corals thrive best in poor conditions, so pollution makes them less competitive. Pollution can also make corals less resilient to seas that are warming up due to climate change. They become stressed and more vulnerable to disease.’

Because of over-fishing, there are also fewer and fewer fish that graze on these algae on the seabed, preventing the formation of massive algal blooms, says De Bakker. ‘And the large-scale loss of grazing sea urchins due to a disease in the 1980s was a setback for keeping algae down.’

Corals thrive best in poor conditions, so pollution makes them less competitive

All is not lost

But De Bakker sees glimmers of hope. He bases his cautious optimism on a second series of photos WUR started taking along the coast of Bonaire in 2014. Marine life and fish stocks are recorded photographically every three years, at 115 spots at depths of 5 and 10 metres. ‘Bak’s series is nice but the photos are of just a few locations, relatively close together,’ says De Bakker. The new series of observations avoid these disadvantages and appear to show that the ecological degradation has stabilized. ‘In a few places, the quantity of certain corals even seems to be slowly increasing a bit.’

The new measurements also reveal large local variations. The reef does best in places with the least human influence. That is the key to success, according to De Bakker: reduce the impact of human beings. ‘For instance, you can make sure there is a good sewage system. Currently a lot of the islands’ wastewater goes into the sea untreated. Sediment also flows from the land into the sea. By planting mangrove forests along the coast you can create natural sinks for nutrients and sediment.’

With such interventions we can improve the situation considerably, says de Bakker. ‘The reef is not lost yet. The reef will never again look the way it did 40 years ago; that abundance of coral is gone. But it is not too late to preserve essential functions of coral. Only we must take action now.’