The common sole is a slippery customer. Like a true Houdini, it can slip through fine mesh, leaving the fisher with a net full of bycatch. WUR scientist Pieke Molenaar is now working with fisheries on developing ‘smart nets’ that trap the sole and keep the rest out. Resource went to sea with him for a day.

It is cold and foggy at seven thirty in the morning as I scan Scheveningen harbour for the TH-10, a cotter belonging to the brothers Johan and Albert Baaij. Fortunately, I had been warned. My warm clothing and high boots are certainly no luxury as I cautiously pick my way across the quay over slimy fish remains, chains and ropes.

Today I am the guest of Pieke Molenaar, a fishing techniques researcher at Wageningen Marine Research, and of fisher Johan Baaij and some Polish crew. At least, I will be if I can find the right boat in amongst the dozens of cotters moored in front of the fish market. Then I see someone waving, a man in a dark blue windcheater with windswept brown curly hair. ‘Come on board,’ calls Molenaar. ‘There are no steps so you’ll have to come down using this rope and the net.’

Trawl

‘Do you want to go for a trawl straightaway?’ asks fisher Baaij once I have reached the deck with a less than elegant manoeuvre. Baaij and his brother often fish for sole and plaice in the North Sea for days on end. They do this with a pulse trawl, a net with electrodes on it that shocks flatfish off the sea bed with small electric surges (see inset). But today the fisher is going to come out with us for ‘just’ a couple of hours, for a ‘mini-trawl’.

Baaij and Molenaar are developing more selective fishing nets together. There is a need for such nets because besides the marketable sole and plaice, Baaij catches a lot of smaller flatfish and other sea creatures. ‘Depending on the fish species you are fishing for, this ‘bycatch’, as it is called, can sometimes make up 90 per cent of the catch,’ says Molenaar.

Fishers used to throw the bycatch overboard. But in 2015, the European Commission made it compulsory to land the fish. That means the fishers must land all the undersized fish of species for which they have a fishing quota. They are allowed to throw other species overboard. The aim of the landing obligation is to combat waste in the fishing industry – the discarded fish do not always survive – and to provide incentives to fish more selectively. And this is where Molenaar comes in.

Coffee in the cabin

It is half an hour’s sailing from the harbour to the place where Baaij wants to fish. Time enough for a bread roll with Dutch prawns and a cup of coffee in the cabin. ‘Ah, coffee,’ sighs Molenaar, ‘I could do with a cup.’ He got back at four o’clock in the morning from a five-day research expedition on the North Sea, so he has only had a few hours’ sleep.

After downing the rolls and coffee, we’re up on deck listening to how Baaij gives the orders to lower the pulse nets over the side of the boat. There is some calling to and fro in Dutch and Polish. The crew, in bright orange waders and matching gloves, are busy throwing the heavy nets overboard. They soon disappear into the dark waters of the North Sea. The boat hardly rolls at all, but from the whitecaps and the swirling water you can see we’re moving quite fast. ‘To catch flatfish you have to keep up a good pace,’ explains Molenaar. ‘Otherwise they dive back into the sand again.’

Starfish and crabs

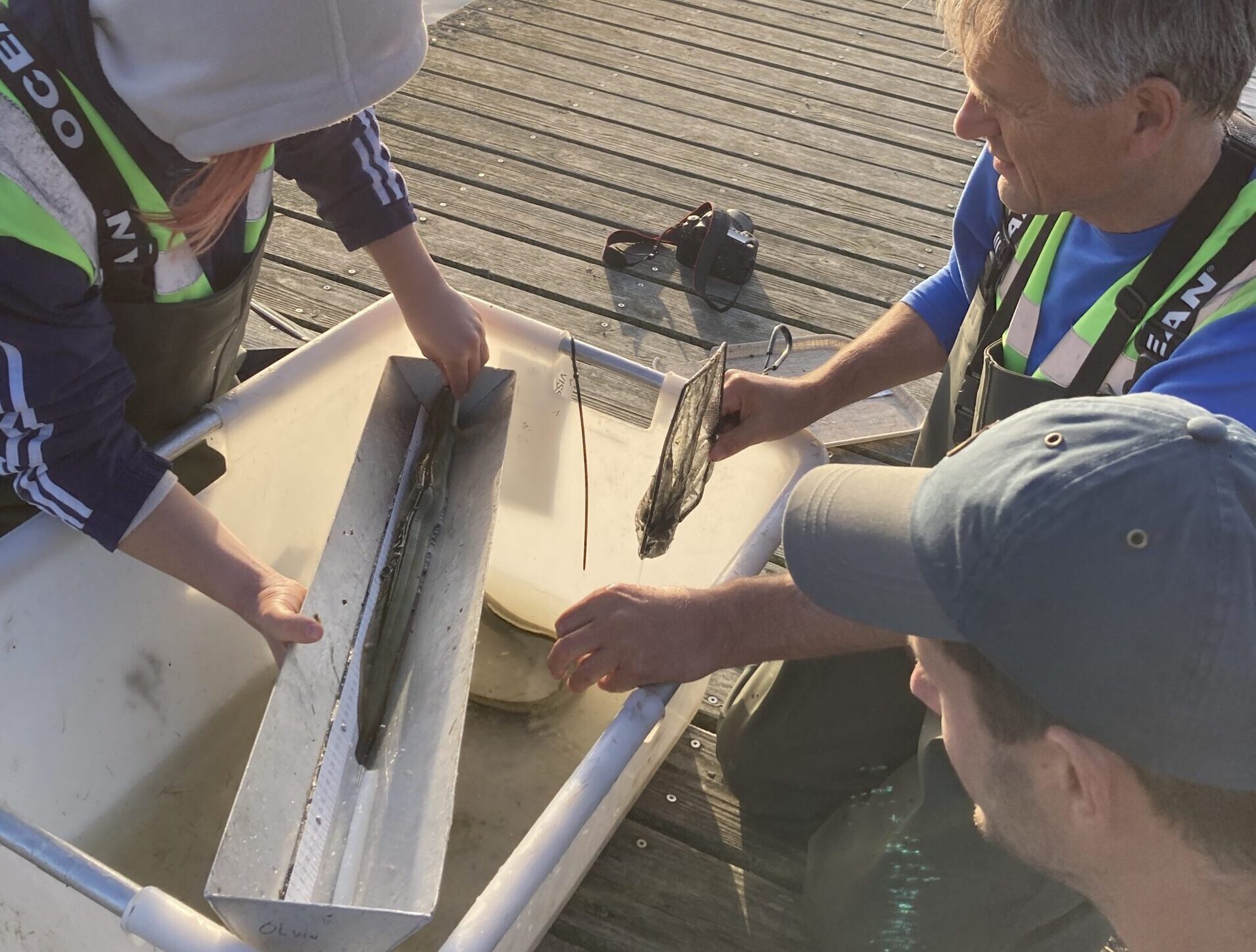

After about half an hour of trawling, the nets are drawn up and emptied into three large orange baskets. ‘Normally everything goes onto the sorting belt and from there into the hold,’ says Baaij. ‘But the belt has just been cleaned.’ Molenaar picks up a couple of fish and puts them on the deck. One flatfish with orange spots is an eye-catcher. ‘A plaice,’ says Molenaar. But the less flamboyant long flatfish lying beside it is the important catch. ‘Sole. That is the most lucrative for the fishery.’

And then there is a colourful collection of sea life wriggling around in the basket. Not just flatfish, but also a lot of small fish, starfish, crabs and the odd mussel. ‘This illustrates the problem of bycatch,’ says Molenaar. ‘We have three baskets full, and about three quarters of a basket is marketable fish.’

Of the three baskets of fish on deck, only a quarter of the catch is marketable

The starfish, crabs, shellfish and small fish can be thrown overboard but not the undersized flatfish. Baaij: ‘I must take those along, even if they hardly fetch anything at all.’ Because of the landing obligation, human consumption of these fish has been banned. This rule was made so fishers don’t start deliberately fishing for small fish. So the undersized fish are processed into fishmeal, which is not very lucrative. Meanwhile, sorting and storing those fish on board is expensive and labour intensive.

Black box

Molenaar has been experimenting for years with smart nets intended to solve the bycatch problem. Together with the Van Eekelen fishery, he has already developed a selective net for langoustines, which has made it possible to reduce the bycatch by as much as 65 per cent. They achieved this by dividing the far end of the net (the ‘cod end’) into several compartments. Fish get into the top compartment, where the mesh is larger so small fish can escape. Langoustines go through a sorting grid with flaps into a different part of the net with finer mesh so they can’t escape.

Molenaar aims to develop similar sorting mechanisms for flatfish fisheries. He has had modest success to date, but he hasn’t given up hope. ‘Up to now, most of the experiments were a question of trial and error. You let down the adapted net on one side, and the standard net on the other. Then you find out whether something works, but you still don’t know why.’ Exactly what went on under water was a black box for a long time. Now Molenaar has found a solution to that.

Filming under water

‘This is the GoPro’, says Molenaar, pointing to a waterproof camera that he has screwed onto a turquoise PVC base together with a lamp. He has attached that base to the net with cable ties so he can film during trawling. ‘Underwater filming in the North Sea is quite a challenge. You have to wait for calm weather. And the net drags along the seabed, stirring up sand that obscures visibility.’ Until recently, Molenaar was therefore unable to film in pulse and bottom trawls. Until he saw the light in September 2016 during an expedition on a German research vessel.

‘I was working on that smart net for langoustines and we were comparing two nets. On one side we got a crystal clear picture and on the other side it was pitch black. Then I realized that the clearer pictures were taken in a cod net, which is a different shape because the end hangs a bit higher above the seabed.’ Back in the Netherlands, he tested his cameras again in the flatfish net, but this time he pulled the end up a bit higher. And that worked.

Escape artist

Thanks to the underwater footage, Molenaar can now see how the flatfish behave in the net. ‘Then the pieces of the puzzle fell into place. When developing those smart nets we first focused mainly on plaice and dab. But on the footage we saw that a plaice shoots through the net at high speed, and doesn’t have time to find the sorting grids.’ Molenaar also saw that sole were much better swimmers and navigators. He thought they stood more chance of getting through and decided to concentrate on these fish. Now he wants to design a sorting grid with which the sole are channelled into a specific section of the net that traps larger fish and allows the smaller specimens to escape.

Plaice get stuck in the net like cardboard, while sole are as mobile as tissue paper

That turns out to be a major challenge. ‘The sole is a real escape artist,’ says Molenaar. ‘Where plaice get stuck in the net like bits of cardboard, sole move about like bits of tissue paper. But just when we try to separate them by making them slip through something, they stop wriggling.’

Molenaar hopes the footage will help the team outsmart the sole after all. ‘Now we can see exactly where the fish swim in the net and how they behave. That enables us to pinpoint far more precisely where we should position those sorting grids.’

Teamwork

Fishers are enthusiastic about the underwater footage too, says Molenaar. ‘Because they see what is going on in the net, they get inspired and come up with new ideas. It is nice to put our ideas together and work towards a solution together. I could think up something myself, but if it isn’t workable for a fisher it is pointless.’

For Molenaar, collaborating with the fishers is one of the nicest aspects of his work. ‘I’ve never really been a landlubber; even as a child I was always fiddling about with rods and fishing nets.’ He says the culture in fishing communities varies a lot. ‘The people in Urk are a bit reserved; they want to check you out first. Whereas Texel people are very direct right from the start.’

After a few hours at sea, we return to the harbour as feeble sunshine starts to break through the fog. We chat a while in a beach café where Molenaar gets a well-earned second cup of coffee. I guess he can go home and rest now? ‘Well, I’ve got to go to another cotter first to pick up some stuff and consult some other researchers.’ The life of a fisheries researcher involves long days without much sleep. But on the plus side, the office is in the fresh sea air, with an unlimited supply of fresh fish.

The efforts of fisheries researcher Pieke Molenaar at Wageningen Marine research to develop selective nets for sole fishers are aimed at pulse trawl fisheries, which are popular in the Netherlands. However, the European Parliament decided on April the 16th to ban pulse trawling from 1 July 2021. Dutch fishers will then have to switch to the traditional beam trawl. That doesn’t render his experiments redundant, though, says Molenaar. The camera images with which he studies fish behaviour in the net could prove useful in developing smart beam trawling nets. But the challenge is growing. Beam trawls have chains that drag over the ground, increasing the bycatch. Exactly what Molenaar aims to reduce with the smart nets.

Photos Tessa Louwerens

Photos Tessa Louwerens