A group of students, most of them from Wageningen, poses in May 1943 in a labour camp of an aircraft engine factory in Germany.

Text Roelof Kleis photos Puylaert family and Guy Ackermans

Just look at them on that photo. They’re only lads, decent lads. Most of them Wageningen students. Looking at the camera with mild amusement. Still carefree and with no idea what the future holds in store for them. On a stool there is a can of coffee and a packet of sugar. But don’t be misled: this is no student society summer camp. This is the labour camp of the aircraft engine factory in Braunschweig, Germany, and it is May 1943.

Etienne Puylaert’s identity card.

Who are these lads and how did they end up here? To answer this question we need to zoom in on the boy in the back row, fifth from the left: Etienne Puylaert, a student of General Agricultural science at the Agricultural College. He sent this photo to his family in Zuiddorpe, Zeeuws-Vlaanderen. He had left home a week ago to go to a labour camp in Germany, because he refused to swear loyalty to the German government of occupation. Working for the same occupier was the inevitable punishment for this. Unless you could go underground somewhere, an option that was not available to everyone.

In line

The Nazis issued their infamous oath of loyalty in the spring of 1943. The Dutch student resistance had taken shape slowly but surely, and one of its greatest feats was the theft of the population register from Wageningen municipal council. This hindered the Germans in recruiting young men to go and work in Germany. Two students were involved in the theft. Along with other acts of resistance, this prompted the Germans to take steps. The idea of the oath of loyalty was to bring students back in line.

They had to go and work in a foreign country, and they didn’t know whether they would ever see their families again

It was a clear choice: sign, and you could carry on with your studied, or don’t sign, and you had to go to work in Germany. In the end the vast majority of Dutch students did not sign. In Wageningen, by the deadline on 4 May 1943, 154 students from the college had signed – one fifth of the total student population. Most of those who refused to sign went into hiding. A total of 150 students reported for duty in the camps.

Folder full of letters

Etienne Puylaert didn’t sign. Why he refused we can only guess, says his son Ben Puylaert. ‘Those are questions I don’t have answers to. My father was a member of the KSV student society at the time. Was he influenced by his Catholic peer group or was it an autonomous decision? He was 20 years old when he had to make that decision. Going into hiding was probably not an option. They would have been able to find him. His father was the mayor of Zuiddorpe. It wasn’t easy to hide in Zeeuws-Vlaanderen anyway. The land is flat and empty, there is nowhere to hide. If you start running away, they’ll see you at once. And he hardly knew anyone outside Zeeuws-Vlaanderen. My father-in-law, who was a student in Wageningen too, lived in Rotterdam and went into hiding there. It is much easier in a big city like that.’

A fragment from a letter from Etienne Puylaert to his family.

Ben Puylaert, a retired electrician, has only recently learned about his father’s war story. Etienne never talked about the war. His hidden past only came to light in 2002, when Ben helped his mother move house five years after his father’s death. ‘When I was tidying up his desk I came across a folder full of letters and photos. They were the letters Pa wrote from Germany, said my mother.’

Leaky boat

Ben Puylaert was astonished. ‘I did know my father had worked in Germany, but he had rarely let anything slip about it. At one point it came up when, sometime in the 1970s, the BBC series World at War came out. Then he mentioned a few little things. That at the end of the war he was on the wrong side of the Elbe, and had to cross it in a leaky little boat to get home. But incredibly little, actually. And nothing about the camps.’

For Etienne’s son, the unexpected find was the start of a long quest. He combed the letters, pored over the photos and searched the internet for clues with which to reconstruct his father’s unknown wartime life. His reconstruction was first shared with others exactly one year ago in De Wereld hotel at a full Studium Generale session. Together with his son Philip Puylaert, who teaches in the Microbiology chair group, Ben brought Etienne’s war years to life with excerpts from the letters.

It was quite an emotional experience, recalls Etienne’s grandson. ‘I had never read those letters properly before. The quest really was my father’s thing. But when I read those excerpts aloud, what he had gone through as a boy really sank in. Of course they were labour camps, not concentration camps. But still. These were boys who were recruited to go and work in a foreign country. Who didn’t know if they would live to tell the tale, or whether they would ever see their families again. It was war. I have students that age in my classes.’

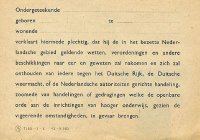

This oath of loyalty was drawn up by the German government of occupation in the spring of 1943 to bring rebellious Dutch students back into line.

Diary

Ben Puylaert has postcards, letters and photos that his father sent home between May 1943 and September 1944. ‘The letters that were written after that, up to Liberation Day in May 1945, are missing. That is because Zuiddorpe was liberated earlier, on 18 September 1944. From then on, it was in enemy territory for the Germans and no more post got through.’ But that last period is described in the diary kept by Fons Crijns, a good friend of Etienne Puylaert’s, and another Wageningen student. Ben: ‘They were together at the well-known boarding school, Rolduc, they both went to Wageningen, and they left for Germany at the same time. Crijns came from Brunssum, which was liberation in September 1944 too. When post stopped getting through he started keeping a diary. My father is frequently mentioned in the diary, just as Crijns is often mentioned in my father’s letters.’

Carpentry

The letters themselves are not very personal. ‘That is what my father was like,’ says Ben Puylaert. ‘He didn’t find it easy to talk about his feelings.’ He didn’t say much in the letters about the work he had to do or suffering he went through. Ben has pieced together some parts of his life like a puzzle. Etienne Puylaert was put to work in four different places in two years. In Braunschweig he worked in an aircraft engine factory. In Uslar, in the middle of the Harz mountains, he assembled wooden ammunition crates. ‘He learned carpentry there and developed a love of woodwork,’ thinks Ben Puylaert. ‘He always wanted to make things out of wood. That is one of those things that fell into place in retrospect. He didn’t learn that at home. My grandfather didn’t even own a hammer.’

Philippe and Ben Puylaert, Etienne’s grandson and son.

Grandson Philippe Puylaert remembers afternoons of woodwork with his grandfather too. ‘He taught me carpentry. I didn’t know him for very long; he died when I was 13. But we always did a couple of hours of woodwork when we visited Grandpa. He was very good with children.’

This wasn’t the only thing that fell into place for Philippe Puylaert as a result of his father’s research. ‘Grandpa never talked about the war. Of course I was still young. But he did always make up stories. A recurring element in the stories was that he was imprisoned in a camp. Not a German camp but a Viking one. The Vikings were the baddies. And there was always an escape in small boats, which were holed so they leaked. Of course we should be careful not to read too much into this. But still, the camps, the Vikings, the boats…’

Duds

After Uslar came a stint in a chemical factory in Herzberg am Harz. Ben Puylaert: ‘There he literally had to stir pots of chemicals. They were making TNT and lots of other ammunition there. Foul stuff. And all without protective clothing. Of course he never wrote about that to his parents. But he does describe it in a letter to a nephew who was studying medicine. That he was in the sick bay, his nails and eyes completely blue from that ghastly stuff. And that his red blood cell count was only 57 percent of the normal level.’

Why did he decide not to sign? Why wouldn’t he ever talk about the war? I don’t know

Towards the end of the war, Puylaert ended up to the east of the Elbe in Glöwen. There he had to take apart duds – bombs that had been dropped but hadn’t gone off. ‘Because of the shortage of raw materials, the explosives had to be knocked out of those bombs,’ says Ben. ‘Using aluminium chisels and hammers, to prevent sparks that might make the bomb explode. So it was risky work. Towards the end of the war, the factory was bombed. My father wrote that he had to hide in one of those empty casings, because there were no air raid shelters.’

In his letters home, Etienne played up the good things. A football match with ‘the farmers’ against ‘the economists’ gets full attention, for instance. Those ‘economists’ were students from Tilburg University. The match, in the camp in Herzberg on 13 August 1944, was a big event that the lads had looked forward to for weeks. The team captains exchanged emblems before the match. The farmers gave a white clog with the wheel from the Wageningen coat of arms on it. They also offered ‘3×20 cigarettes for the person who guessed the final score correctly,’ writes Puylaert in one of the letters. After a 1-1 draw, the economists finally won 3-1.

In August 1944, the Wageningen students in a camp in Herzberg played against Tilburg students in a football match.

Suppressed

Towards the end of the war, Puylaert and his friend Crijns crossed the Elbe in a small boat. Travelling in an open railway wagon, they reached Simpelveld in South Limburg in four days. It was early May 1945, and it would be the last time they saw each other. ‘Those two never sought contact with each other again. Never again!’ Ben Puylaert is silent for a while. ‘I find that most intriguing and poignant. Friends since boarding school, going through everything together right up to liberation. And never looking each other up again. Did they consciously want to close a chapter? Were the memories too painful? I asked Fons Crijns, who I got the chance to meet. He didn’t answer. He too said nothing about the war all his life. He didn’t even show his diary to his own wife! Those people suppressed an awful lot.’

Etienne Puylaert arrived in Zuiddorpe on 4 May 1945. He took up his studies in Wageningen again later that year. He would eventually go on to be the founder and first director of the Agricultural College (HAS) in Den Bosch.

‘I lined up the facts,’ says Ben Puylaert, when asked why he embarked on this quest. ‘I wanted to know where he had been and what he had to do. I succeeded in that. But I know nothing about his feelings and thoughts. What made him decide not to sign the oath of loyalty? Why wouldn’t he ever talk about the war? Was his experience so terrible? I won’t get answers to these questions.’

TIMELINE

1943: The German government of occupation forced students to sign an oath of loyalty; Etienne Puylaert refused and was sent to work in Germany. 1945: End of World War II. Puylaert returns home and takes up his studies in Wageningen again.

Play: Marked!

The oath of loyalty students had to sign during the German occupation is the subject of a spectacular theatrical production in the Junushoff between 6 and May. Students and staff of WUR have worked alongside professional theatre-makers to create this production. Tickets can be reserved on the website getekendwageningen.nl.