(Photo: Floris van Breugel, Dickinson Lab)Wing damage is frequent in birds and insects. Birds have found a way of dealing with this: moulting. They regularly grow new feathers. Insects, however, don’t have such a repair service. Insects with broken wings have to live with the problem. And they do so successfully. Even removing half a wing has hardly any consequences for their flying skills. How do they manage this?

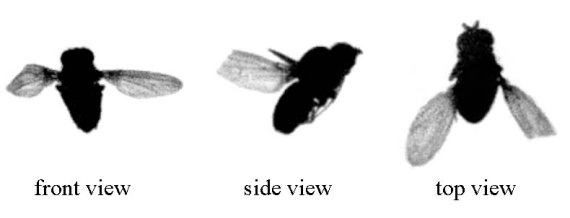

Florian Muijres explains this in Interface Focus, a journal that focuses on the area between biology and physics. Working with fruit flies, Muijres cut off part of one of their wings and then analyzed their resulting flight behaviour. To do this he used three perpendicularly positioned high-speed cameras that recorded flights at 7500 images a second. This provided him with a mountain of information about the wings’ patterns of movement, the speed at which the wing beats and the position of the fruit flies’ bodies in the air.

On a roll

A damaged wing has less lifting capacity. And the remaining capacity is divided asymmetrically. One wing lifts more than the other, resulting in a rotation when the fly rolls to the side of the damaged wing. If the fly fails to act, it will start to roll and will fall to the ground. But that doesn’t happen, as shown by the images and analyses of Muijres and his American colleagues at the University of Washington.

On the contrary. Suddenly and seemingly without effort, the fly adjusts its flying behaviour. It seems that the reduced lift capacity is compensated for only by beating faster with the wings. The frequency of beating increases by about 10 percent, according to Muijres. To give an impression of what that means: a normal fruit fly beats its wings about 200 times a second. To measure any differences, you need a high-speed camera.

Actually, the fly should only beat its broken wing faster. But that’s impossible

Florian Muijres

But this isn’t enough. The faster beat doesn’t stop the rolling movement. In fact, it becomes even worse as the wings beat faster. Actually, the fly should only beat its broken wing faster. ‘But that’s impossible,’ said Muijres. ‘Flies can only beat both wings at the same frequency.’ To escape from the ‘roll’, the fly does something else: it adjusts the size of its wing beat.

Fruit fly with a cut wing

Recorded with a high-speed camera (images: Florian Muijres)

Breast stroke

The way insects beat their wings looks a bit like rowing or the breast stroke. The fruit fly makes a bigger stroke from front to back and then back again with its broken wing. At the same time, the intact wing makes a shorter stroke than it used to. This asymmetry stops the rolling movement. The result of all of the kinematic forces involved is that, while flying through the air, the fly is slightly (10 percent) inclined towards the damaged wing. And it has less forward acceleration.

‘The most surprising,’ said Muijres, ‘is that the whole system is modular. The loss of lift is fully solved by a faster wing beat. The rolling movement is halted by adjusting the stroke of the wings. Both aspects are independent of each other.’ And with these adjustments the fly can still make all of its flying movements, according to Muijres.

‘Fruit flies have evidently evolved to be able to deal with damage,’ Muijres concluded. ‘Adjusting for damage is an integral part of the fly. There is extra capacity on board to cope with damage. Broken wings can thus make much bigger wing beat-amplitudes than what you see in a normal flight.’ But there is an obvious limit to how much a fly can compensate for its rolling movement: the wings cannot make a stroke bigger than 180 degrees because they’d otherwise hit each other. Muijres said that the limit is reached when the wing is halved.

Robot

There’s also a practical use to knowing how a fruit fly stays in the air. Technologists in Delft are making grateful use of this knowledge to teach their flying robots (micro-air-vehicles) to fly. With funds from the STW, enough for two trainee research assistants, the project will have a follow-up. Muijres: ‘We’re going to study how flies react to gusts of wind. How they deal with changing wind. Delft wants to apply that knowledge to their tiny robots.’