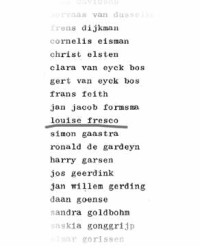

Student – Living in a Ceres box

It was hardly surprising that Louise Fresco chose to go to university. He father was a philosophy teacher and owned an extensive library, the contents of which were eagerly devoured by the young Louise. Meanwhile, she went to the international school in Brussels, where her father taught. So an academic career was always on the cards. But her choice of discipline was interesting. Had she followed in her parents’ footsteps, she would have gone for art history or a language. But Louise opted for nonwestern Rural Sociology. In Wageningen. She studied here from 1970 to 1976, and for the first few years was a member of Ceres. At the time, men’s and the women’s student societies were starting to merge and Ceres was the first mixed student society in the Netherlands. It is not clear how active Louise was, as she is not listed as a member of any of the many committees. But in 1973, she did live in a Ceres house at Hoogstraat 63a. Before that she also lived at Hoogstraat 14 and Koningin Julianastraat 4. There was a shortage of accommodation in Wageningen at the time, and the big tower blocks of student flats were going up. As a child Louse played the flute and as a student she was a member of the Wageningen Student Choir and Orchestra Society. Oddly enough, she played the double bass in the Christmas concerts of 1971 and 1972. At the start of her student career, Louise was involved in the SIB, the student society for international relations. Her first scientific works can be found in the university library. In 1974, she helped with Farmers’ Training Centers, a project which besides providing a training programme for farmers, was also an exercise in systems thinking. The conclusion of her own dissertation on ‘Households and women in a changing rural society’ starts with the sentence: ‘A dissertation in which so many questions are raised and so few are answered can hardly end by presenting conclusions.’

Scientist – Creative burst of ideas

‘The joke about people like Louise Fresco is always that you need to go after them with a vacuum cleaner to collect up all the good ideas.’ Researcher Jetse Stoorvogel (Soil Geography and Landscape) laughs. This is what he experienced when his supervisor Fresco visited him in Costa Rica, where he was doing research. ‘You sit down with her and she spouts ideas. And coming from her, it all sounds marvelous.’ But after her whirlwind visit was over, hard reality returned: ‘Yes, but how am I supposed to carry that out, and is it all really feasible?’ It is a familiar story for (former) colleagues. Fresco‘s verbal skills are legendary. ‘She is terribly good at presenting things and at brainstorming,’ notes professor of Plant Production Systems Martin van Ittersum, who once taught in the Theoretical Production Ecology chair group. ‘That way she achieves a lot and makes a big impression on people.’ But what has Louise Fresco actually achieved in the scientific arena? A brief search through Web of Science for papers in peer-reviewed academic journals leads to a small surprise. For a scientist of Louise Fresco’s stature, she has an extremely modest track record. The data base only comes up with 43 articles, most of them collaborations with PhD students dating from her Wageningen years as professor of Plant Production Systems. Nevertheless, her work gives her an H factor of 20 and a citation score of 961, not including self-citations. Just as striking is the fact that she is still cited quite a lot. Between them, her papers have been cited about 80 times a year for many years. The most cited are the two papers she published in Ecological Modelling in 1996 together with Professor Tom Veldkamp (Spatial Environmental Quality) of the Technical University of Twente. These papers were about the land use model they developed, called CLUE (Conversion of Land Use and its Effects)

‘The joke about people like Louise Fresco is always that you need to go after them with a vacuum cleaner to collect up all the good ideas.’ Researcher Jetse Stoorvogel (Soil Geography and Landscape) laughs. This is what he experienced when his supervisor Fresco visited him in Costa Rica, where he was doing research. ‘You sit down with her and she spouts ideas. And coming from her, it all sounds marvelous.’ But after her whirlwind visit was over, hard reality returned: ‘Yes, but how am I supposed to carry that out, and is it all really feasible?’ It is a familiar story for (former) colleagues. Fresco‘s verbal skills are legendary. ‘She is terribly good at presenting things and at brainstorming,’ notes professor of Plant Production Systems Martin van Ittersum, who once taught in the Theoretical Production Ecology chair group. ‘That way she achieves a lot and makes a big impression on people.’ But what has Louise Fresco actually achieved in the scientific arena? A brief search through Web of Science for papers in peer-reviewed academic journals leads to a small surprise. For a scientist of Louise Fresco’s stature, she has an extremely modest track record. The data base only comes up with 43 articles, most of them collaborations with PhD students dating from her Wageningen years as professor of Plant Production Systems. Nevertheless, her work gives her an H factor of 20 and a citation score of 961, not including self-citations. Just as striking is the fact that she is still cited quite a lot. Between them, her papers have been cited about 80 times a year for many years. The most cited are the two papers she published in Ecological Modelling in 1996 together with Professor Tom Veldkamp (Spatial Environmental Quality) of the Technical University of Twente. These papers were about the land use model they developed, called CLUE (Conversion of Land Use and its Effects)

. At the time, Veldkamp was a postdoc in Fresco’s group. The model predicts changes in land use based on the recognition of patterns. According to Veldkamp, she was one of the people who launched a new branch of science. ‘She has a good nose for what is going on, for new developments. Like that she put me on the modeling track.’ ‘Her real contribution to the field is that she taught us to think in terms of hierarchies of scales,’ says professor of Crop Physiology Paul Struik. ‘She looked at agriculture as a whole, with processes going on at different scale levels.’ But besides her creativity, Fresco could also be very concrete, says Stoorvogel. ‘At one point she came for a three-day visit. In that time we put together a complete scientific article. That was the only paper I have ever submitted that got through the review without comments. At a time like that she was totally there for you.’

Executive – Averse to dogma

Louise Fresco develops a vision, looks for good people to implement that vision and gets things done by persuading other people to do them. So says Rudy Rabbinge, who has known Fresco since 1970. ‘Fresco is averse to dogma. She wants to use all the available knowledge in the service of her ideals.’ After her studies at Wageningen, Fresco shot up the academic ladder to the position of professor at Wageningen. She then moved into the world of management when she accepted the post of head of the research department at world food organization FAO – surely the perfect place from which to really be able to boost agriculture and food production. But that turned out to be an illusion. ‘At that time the UN was doing too much navel-gazing and lost its position,’ says Rabbinge. ‘Fresco ran up against a boss who didn’t want to change anything and ran the FAO like an African tribe- everything had to go through him.’ Eventually this led to Fresco resigning from the FAO, in a letter that stated clearly what kind of management style she likes to see. From her letter: ‘FAO needs visionary leadership to move itself out of its bureaucratic paralysis. (…)

Louise Fresco develops a vision, looks for good people to implement that vision and gets things done by persuading other people to do them. So says Rudy Rabbinge, who has known Fresco since 1970. ‘Fresco is averse to dogma. She wants to use all the available knowledge in the service of her ideals.’ After her studies at Wageningen, Fresco shot up the academic ladder to the position of professor at Wageningen. She then moved into the world of management when she accepted the post of head of the research department at world food organization FAO – surely the perfect place from which to really be able to boost agriculture and food production. But that turned out to be an illusion. ‘At that time the UN was doing too much navel-gazing and lost its position,’ says Rabbinge. ‘Fresco ran up against a boss who didn’t want to change anything and ran the FAO like an African tribe- everything had to go through him.’ Eventually this led to Fresco resigning from the FAO, in a letter that stated clearly what kind of management style she likes to see. From her letter: ‘FAO needs visionary leadership to move itself out of its bureaucratic paralysis. (…)

I believe in an organization which is not afraid to make clear and precise choices, learning from the past without taking the past as a recipe for the future. I believe in an organization where we worry less about rules and more about the impact of our work. I believe in an organization which sees its staff as a source of inspiration and allows them to be mobile and grow.’ And this seems to be the approach she intends to promote in Wageningen too. Between now and September, she has stated through the Communication department, she is going to talk to a lot of people to get a picture of Wageningen UR,. She then wants to share her vision with the rest of the organization at the opening of the academic year.

Author and documentary maker – Utopian and cosmopolitan

‘You could call it a miracle that someone in a top public job like Louise Fresco found the time to produce such a rich, multifaceted and well-written novel,’ wrote reviewer Elsbeth Etty of Fresco’s debut De Kosmopolieten. Yet she went on to write two more novels in the years that followed. And one of them, De Utopisten, although not uniformly well-reviewed, was nominated for the Libris literature prize. Fresco does not just write novels, but in 2012 also produced a ‘big book’ about food. In Hamburgers in het Paradijs she shows how we deal with food in our culture and science. It is very unusual for one person to write both novels and non-fiction of this quality, says Job Lisman, Fresco’s editor at publisher Prometheus/ Bert Bakker. A year later, her book was turned into a documentary series called Fresco’s Paradijs. In it we see Fresco in a wetsuit going in search of edible algae in Spain, or standing outside a seed bank on Norway. We also hear her talking to food experts and enthusiasts in practically fluent French, English, Spanish and Italian. According to Lisman, working with Fresco is incredibly stimulating. ‘Many writers are only interested in their own work. With Louise, from the start the conversation will be about some social issue, or an exhibition or concert she has been to.’ Several of her interests – classical music, idealism and sustainability – are reflected in her novels too. In Fresco, Wageningen is gaining a good colleague, thinks Lisman, and he can only foresee one disadvantage: ‘I hope we won’t have to wait too long for her next novel.’

Missionary – Little time for bigots

‘As a child I wanted to be an Albert Schweitzer,’ Louise Fresco told the NRC newspaper in 2012. ‘Doctor, theologian, philosopher, musician and missionary all rolled into one – what could be finer than that?’ Over the years she grew wiser and changed her ambitions, but Fresco still sees herself as an idealist. People should not just look after their own interests, she says in interviews, but should also strive to make the world a better place. This was why, as a child from the ‘sheltered and cultivated middle class’, she opted for tropical agriculture and not an arts degree. The missionary in Fresco always has stories for her audience, whether in interviews, professional advice, lectures or books. In fact, she sees this communication as actually essential to her thought processes. When she speaks, she is erudite, scientifically sound, and fond of a helicopter view of things. She offers an optimistic perspective on the future. She believes that science and human inventiveness will enable us to continue to feed the world in future and to go on finding solutions to our problems. But she has an eye for the nuances of her subject and applauds the critics of technology – her own critics. They ensure, she says, that expectations are kept within the bounds of realism. She has little time, however, for bigots who are nostalgic for a ‘mythical past’. In an opinion piece in Science in 2012, she put European opposition to genetically modified crops down to a growing distrust of science. In spite of the nuances in her argument, Fresco’s articles draw a lot of criticism. There were some fiercely critical responses to her Science article, including one from Wageningen. Fresco’s TED talk provoked a heated online discussion in which she was portrayed as the puppet of ‘big agri’. Par for the course now that agriculture are food are so controversial.

Louise Fresco

- Her full name is Louise Ottilie Fresco

- Born in Meppel on Monday 11 February 1952

- Grew up in an ‘academic’ family. Her father was a professor of philosophy.

- Fresco is single and has no children. She lives in Amsterdam.

- She has written four books (fiction), her 1990 debut being a collection of short stories Bambusa.

- Her latest and perhaps best-known work of non-fiction is Hamburgers in Paradijs, 2012.

- A long list of positions, prizes and publications can be viewed at www.louisefresco.com or www.nl.wikpedia,org/wiki/Louise_Fresco