Dilemma 1: deposits or collection?

This is a current issue because earlier this month state secretary Mansveld decided to keep the deposit on PET plastic bottles for another year. The plan to scrap the system in 2015 was partly based on a Wageningen report on how much it costs. A new report, commissioned by a producer of deposit machines, came up with different figures, however, casting doubt on the plan. In the political commotion which followed, Mansveld decided to postpone the move.

But what is better, generally speaking: a deposit on bottles or collecting plastic? The advantage of the deposit system is obvious, says Jacqueline Bloemhof of the Operation Research & Logistics chair group. It means you get a nice, uniform flow of plastic waste which is easy to recycle. Compare that with the jumble of different plastics you get with voluntary collection, of which 76 percent is plastic and the other 24 percent waste. What is more, half of the plastics are mixed and can only be used to make roadside posts, at best. Only the remaining 38 percent is high quality, but is still a mixture of plastic types such as PET, PE and PP. This makes for a complex and therefore expensive puzzle.

But the deposit system comes with a hefty price tag too. This is because the bottles must be transported whole by truck from the supermarket to the terminal and from there to the sorting centre. You are transporting a lot of air that way, says Ulphard Thoden van Velzen of Food and Biobased Research. Otherwise it is difficult to administrate the deposit charge at a retail outlet – a petrol station along the road, for instance. The logistics and the bookkeeping of PET bottle recycling are highly complex and make this waste flow particularly expensive.

Dilemma 2: Sorting by consumer or at the plant?

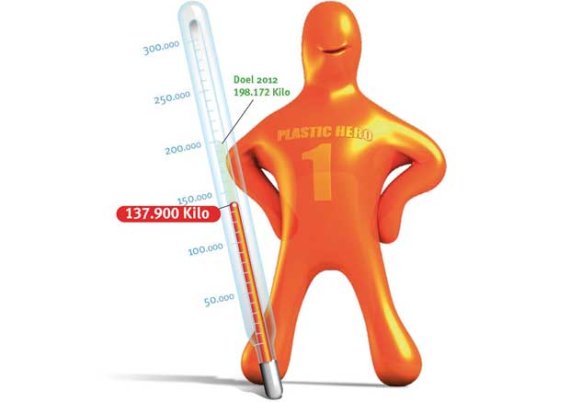

However much fuss there has been about the PET bottles, deposit money on plastic remains a marginal issue. About 90 percent of all the plastic used ends up in the general waste flow and has to be fished out of it. So what’s the best way of doing that – to get the consumer to do it, or do it after garbage collection? In the first scenario, the consumer collects the plastic in a separate garbage unit, which could be a bin, a bag or a central collection point in the neighbourhood. The highest scoring municipality in the Netherlands is one in Limburg which manages to collect 60 percent of the plastic waste. Forty percent still ends up in the grey bin for general waste, no matter how hard we try. The problem is that a lot of plastics are not recognizable as such. Plastic bottles are easily identified, butter packets less so, and plastic foils much less so. It helps if the producer makes plastic packaging more recognizable as such, say the researchers.

The other alternative is for the waste processing company to sort the plastic from the general waste at the collection point. There is now modern equipment which can extract 60 percent of the plastic from the general waste flow, a score which equals that of the residents of the Limburg municipality. And according to Thoden van Velzen, that leads to a surprising conclusion: we can recycle the most plastic waste by going all out for modern sorting equipment. But the price can be a problem here too, because separating plastic at the waste plant is expensive. And to complicate matters further: there is a big difference between urban and rural residents when it comes to sorting waste materials. Flat residents are not as good about it as households with their own sheds. So separating plastic waste at the plant might be the ideal solution for Amsterdam, but not for Bennekom.

Dilemma 3: house-to-house collection or a central collection point?

If you decide to get consumers to do the sorting, you run up against a new dilemma. Take Wageningen municipality, for instance. Currently, Wageningen residents are expected to bring their plastic waste to bins located at the supermarket. But if the town council has its way, in a few years the municipality will be collecting everything separately from households. Then Wageningen households will put their plastic waste out for collection in a bin (as they do with paper and green waste) and will have to dispose of the remaining waste themselves.

That would seem a sensible and environmentally friendly policy, but is it really? No, calculated the Wageningen PhD student Xiaoyun Bing. In rural municipalities such as Wageningen, the recycling system in which people put their containers out on the pavement for collection costs twice as much as the recycling bins at the supermarket. What is more, the bin on the pavements is less environmentally friendly. Separating rubbish leads to a half-full grey bin and a half-full plastic bin. The garbage trucks use a lot of fuel due to all the stopping and starting, so the environmental score per ton of waste is low. Bing also reckons you get the lowest emissions if people bring the plastic to the recycling bins themselves when they are going shopping anyway.

Others think the house-to-house collection system can be made more efficient, though. But then the municipality should combine the waste flows of plastics, deposit bottles and drink packets so that the bins for separate collection are much fuller. One of the problems with the three collection systems – deposit money, household waste separation and separation at the plant – is that they hinder each other. If you expand one of the three systems, that automatically leads to poorer results for the other two. The more plastic waste flows you can combine, the more efficient the recycling is.