A pile of DVDs at least ten years old, with the contents of the hard discs of several ex-researchers, landed on Annemarie Patist’s desk at the WUR library recently. A chair group wanted to keep its ex-employees’ research data safe. The contents of the discs turned out to be chaotic, however, with the data of the different researchers all mixed up, and old and new versions too. There was a general lack of clarification, referencing and reliable dating. An insoluble puzzle, concluded Patist. The DVDs disappeared into the wastepaper bin, and with them years of data.If things go well, these kinds of anecdote should become a thing of the past as of 1 April. From that date, every new PhD student starting in Wageningen will be expected to have a data management plan. This forces the researchers to think about how to carefully collect, manage and store their data before they even start on the real work. It is not just the individual researchers who will have to toe the line: all the chair groups have to present a data management plan at the beginning of April, too. This means the new data rules will affect the work of all Wageningen researchers.

Powerless

New rules in the area of data management have been in the offing for some time, but the recent fraud scandals involving the scientists Diederik Stapel and Dirk Smeester caused the plans to be fast-tracked. In the Smeester case in particular, data played a key role. The Rotterdam marketing professor persistently denied having made up data in the way Stapel did. But he could not prove it. His paper questionnaires had got lost in a move, and the digital databases were lost, he said, when his hard disc crashed just before the investigation into his integrity. ‘Implausible,’ concluded the investigating committee through gritted teeth, but they were powerless. This led to a general discussion about dealing with data. Stricter rules, people argued, make fraud less tempting. And when it does happen anyway, it will be easier to notice it and prove it. An investigation by the Royal Dutch Academy of Sciences (KNAW) advised universities to adapt their code of conduct on data management. The new Wageningen rules are a direct result of this advice.

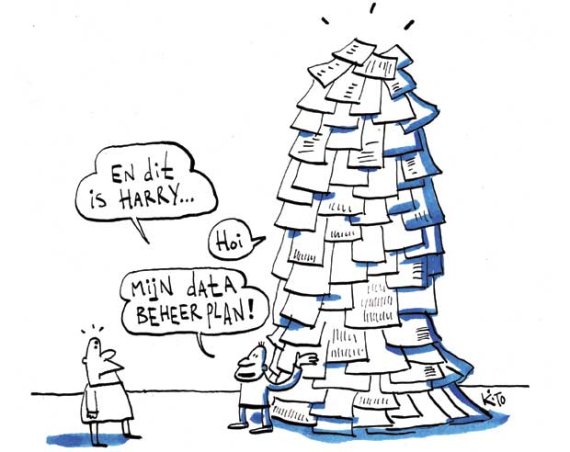

Bureaucracy

Hugh Besemer, information specialist at the WUR library, has mixed feelings about the fraud story. On the one hand, it is good that the fraud cases have put the data problems on the agenda. On the other hand, he thinks the new rules should not be seen as a sign of distrust or a way of making like difficult for scientists. He says a good data plan is a small investment with a big return: ‘You really do make it for yourself.’ Scientists with a good plan work more systematically, he says, and they can find and understand their data again more easily, even years after compiling them. Besemer also reckons that organizing data meticulously will help PhD students write their theses faster. ‘Sometimes their information is so messy that they just cannot get their research down on paper.’To help researchers draw up their management plan, the library has been running courses on data management for several years now. The participants in the first few courses tend to look back on them positively. ‘The course forces you to think about how you can store your data logically and clearly,’ says Lucie Vermeulen, PhD student at Environmental Systems Analysis. Another PhD student, who expects to collect ‘several dozen terrabytes’ of data, only realized during the course how difficult it is to store that much data securely, especially in the long term. Because he ran up against this problem so early, he now has plenty of time to ponder solutions. This is precisely the sort of active thinking that Besemer want to encourage: ‘People often say during the course: “I have never thought about that”.’

Untraceable authors

And that thinking seems to be sorely needed. A recent study in Current Biology shows, for instance, that scientists do not have much idea how to store their raw data securely in the long term. The paper took 516 ecology articles published between 1991 and 2011 and checked whether the data could still be traced now. For the last two years of the period it was possible, but the chances of success got smaller with every year further back in time. For the articles published in the early 1990s, there was only a 20 percent chance of finding the data. And across the board, it was only possible to trace 40 percent of all the authors. The disappearance of these data represents a massive waste of time, effort and taxpayers’ money. Above all, data loss is a loss to science. This is because data can have a productive second life. For reliability, for example, it is important for scientists to repeat each other’s analyses in search of errors. Also, in the course of time, new analytical techniques appear, making it possible to extract sharper or new conclusions from the same data, sometimes in combination with data from other experiments. Lastly, scientists can pose all sorts of new questions in relation to the data. One example is the way weather data collected by meteorologists over the past 100 years are now used to study climate change. And very old hunting data in Canada enabled ecologists to discover how the population size of prey and predator animals influence each other. If data collects dust in shopping bags and on floppy discs, it will never have the chance of a second life. But under the new regime, that will no longer happen.

No hard-and-fast rules ## A communication scientist uses very different kinds of data to a plant scientist. The university has not therefore laid down detailed rules for the management plan. There is only one example plan made by the WUR library, which PhD students can adapt to their own situation. A good plan should in all cases make clear who is responsible and who the owner of the data is. Researchers are also expected to think about how to make sure they or their successors will still be able to find and understand the data in a few years’ time. Databases should therefore carry a clear name and date, and should be logically organized in folders. And computer programmes should still be able to read them in 10 years’ time. And of course, during and after a PhD graduation all these data are on a hard disc where anyone interested can find them.