A Dutch guide called What’s in your food? sold about 180,000 copies. The grim little guide systematically describes all the EU-approved additives or E numbers. And comes to the conclusion that about 80 percent of them are suspect or downright dangerous. ‘Poison in our food,’ concludes publisher Will Jansen. Jansen’s book may be an extreme example, but that does not change the fact that many people feel uneasy about the additives in our food. Food producers add these substances to improve the quality or appeal of their products. Preservatives ensure that a quiche keeps longer, for instance. Colorants make custard look nice and yellow or strawberry jam a tempting red.

It seems ironic that of all the additives in circulation, it is those with E numbers that come under fire. The whole idea of the E number was to provide a safety indicator for additives. A substance may only carry an E number if it has been extensively tested for damaging side-effects by the EFSA, the EU’s food safety authority. Moreover, the substances are only permitted at a daily dose which you could safely consume every day all your life without any risk of side effects.

Ignorance

There has been widespread unease about additives for decades, but processed food is particularly at odds with the spirit of our times. The food trends of today revolve around organic, authentic and ‘natural’ food. In this climate, E number-free cookbooks are appearing in the bookshops and there are numerous websites devoted to ‘unmasking’ E numbers. Any coverage of E numbers in the Dutch national press is almost always negative. Discussions of the topic quickly tend to become heated. And this is because we no longer have an overview of how our food is produced, says philosopher Dirk Haen of the University of Maastricht. He says consumers are suspicious when they buy factory-processed foods, and this sentiment is reinforced by the mysterious numbers on the packaging. Ignorance about our food does the rest. ‘We are increasingly dependent on experts for knowledge about what we eat,’ says Haen. ‘And they sometimes contradict each other, making it very complicated to know what you should believe.’

How do you convince an avoider?

Why do consumers avoid E numbers? Elleander Paans, MSc student of Applied Communication Science, addressed this question in her thesis. When she noticed in a survey that the more consumers know about E numbers, the more positive they are about them, she wondered whether there was a causal relation there. She then did an experiment in which two small groups of about 20 people each were given an information booklet to read. The one booklet contained general nutritional information, and the other contained specific information about E numbers. The participants then answered a number of questions about additives. Paans found that the ‘E number group’ did indeed get more answers right, but that their beliefs had not significantly changed. More information alone, suggested the experiment, is not enough to remove scepticism. But people’s actions don’t always match their words. Of the consumers who intend to eat fewer E numbers, only a small proportion actually avoid processed food products. Practicality wins over idealism.

Salt

But what do the critics actually want? For Will Jansen, publisher of the little black guide, the norms for additives in Europe are not strict enough. He argues for a strictly conservative approach in which substances are not permitted until it is absolutely certain they are safe. According to professor of Food Technology Tiny van Boekel, this may superficially sound like a reasonable proposal, but there are two big problems with it. One is that critics forget that it is the dose which makes something poisonous. Van Boekel: ‘Salt is poisonous if you eat too much of it, yet it’s on the table everywhere.’ Secondly, Van Boekel feels the requirement that a substance should be 100 percent safe is unreasonable. ‘You can never scientifically prove that something isn’t safe,’ he says. ‘We can only demonstrate with all the means at our disposal that something is very probably not toxic.’

Salt is poisonous if you eat too much of it, yet it’s on the table everywhere

This discussion about safety has been going back and forth for some time, says philosopher Haen. In one of his articles, he declares that the scope of the discussion needs to be widened. Consumers are worried about much more than just safety and health. They observe the rise of packet mix cookery and they question whether it is the right way to go. Isn’t all that convenience food detrimental to our gastronomic and culinary culture? And in future will we still take the time for a good meal with our families? ‘So consumers are asking themselves what the good life is,’ says Haen, ‘and what the role of food is in it.’ As long as the nutrition professionals focus only on safety, they might as well talk to the wall, he thinks.

Clean labels

Food technology professor Van Boekel is not afraid to enter the fray. ‘Issues outside my field are open for discussion too, as far as I’m concerned. What do we see as good food, and what not? And how do we organize our food production? It is his belief that debate is the only way out of this crisis of confidence. So Van Boekel regularly attends discussion evenings, and he is disappointed that the food industry is often conspicuous for its absence. That is an error of judgement, he thinks. Companies should explain why they use additives. ‘Be proud: additives raise the quality of food. What is more, we use them ourselves in the kitchen, only there they are in lemon juice or milk.’

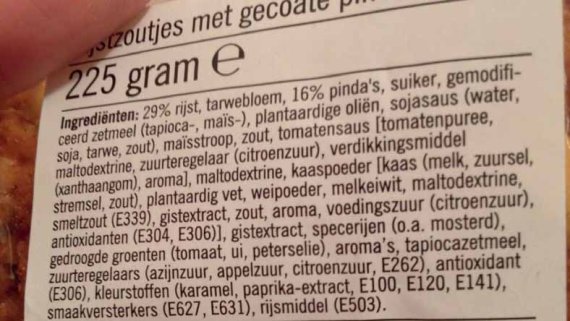

The food industry is quietly adapting, but it is doing so in precisely the way Van Boekel would rather not see. One example is food products which now bear ‘clean labels’: labels with no E numbers on them. These are often cosmetic changes designed to reassure the customer. The label gives the name of a substance instead of its E number. Or an artificial substance such as citric acid is replaced by lemon juice so that officially no additives have been added. Marketers are playing to consumer anxieties too. Now and then you see cheese or sausage in the supermarket bearing the proud news that it is ‘E numberfree’. Seems like a recipe for even more anxiet.