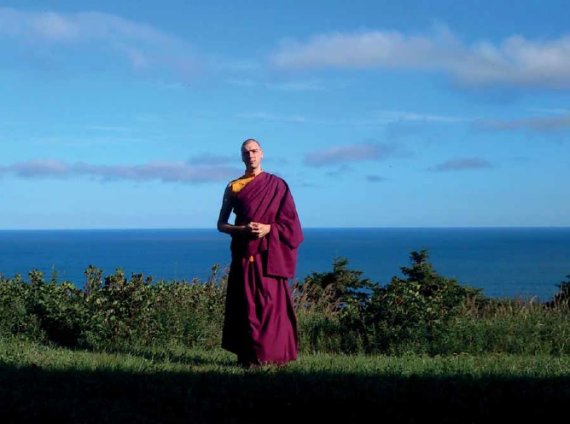

Thomas Koot, Msc student of Agrotechnology. Buddhist, spent a month in a monastery in Canada

‘When I was 16 I first became interested in Buddhism through an article in the Volkskrant newspaper. I then went with a friend to Dechen Chöling, a Buddhist centre in France. That was an extraordinary experience. I met a lot of interesting people there who all feel a sort if dissatisfaction with the superficiality of everyday life. Last summer I spent a month as a monk in a Buddhist monastery in Canada, which was something I had been intending to do for a long time. For the first few days I was preoccupied with things like: will there be something nice to eat tonight, or won’t I get too many aches and pains from meditating? Slowly my thoughts settled on more basic underlying feelings, and then suddenly you can feel very alone. You can also feel an intense appreciation of the world around you. We meditated from sunrise to sunset, you were not allowed to talk, you had no access to the internet, and we only ate twice a day. If you don’t talk, you cannot hide behind empty words. In spite of the fact that we didn’t talk, we got to know each other very well. That might be hard to explain, but it did feel that way.

Buddhism is based on inner power. In a country such as Bhutan, which has always been Buddhist, it is more religious in nature. In the West it is more that the Buddhist philosophy and practices have been taken over, but the basic idea remains the same: that people suffer because of attachment, or craving. Meditation is a training to let go of that attachment, and you don’t need any higher powers in order to do that. When you meditate you just sit and watch what happens. If a though comes up you let it pass. It would be too simplistic to say that I want to live completely in the here and now, or that you have to banish all thoughts, but by meditating you do learn not to get carried away by your thoughts. It is a pitfall in life to live from one distraction to the other. There is nothing wrong with distraction, but sometimes opting for silence and solitude feels nicer than an afternoon spent on Facebook.’

If you look at the agenda of the SP&C (Student Platform and Chaplaincy) you will soon understand what we are talking about here. On weekdays there is an event on almost every evening, ranging from a Socratic café to a Taizé Celebration. Each event is an opportunity for participants to get their religious and philosophical concerns off their chests. Most of the events are always well-attended, says student chaplain Yuri Saris, who has seen a rise in student interest in recent years. The same goes for international students, who have been coming along en masse since it was decided last year to conduct the whole programme in English.

‘The Christian faith is no longer such a presence in the Netherlands, but students still have the same questions about the meaning of life,’ says Saris. Your identity is not as fixed as it was in former days, he says. And yet students still have to find their own place in society. That is not made any easier if your parents have left you entirely free to make up your own mind. So the SP&C offers guidance without steering people towards any one belief in particular. ‘As soon as you address the often unspoken inner turmoil that students experience, there is something spiritual involved. In other words, you touch the spirit, not just the rational mind’: this is how Saris sums up his work.

A different quest

Philosopher Rudi te Velder, too, notices an increasing interest in spirituality among students. He puts it down to the way science has taken over from religion when it comes to explaining reality. ‘If you make science the source of absolute truth, the result is that students react and go to the other extreme,’ asserts Te Velde. He is referring to scientists who claim that a human being is no more than a machine, such as Dick Swaab in his book We are our brain. According to Swaab, there is no such thing as free will, so our life story is not a path we choose for ourselves, but the result of the interaction between neurons and protons. According to Te Velde, however, this kind of story is not much use to you if you aim to lead a meaningful life and therefore have to make big decisions. So it is logical that students look elsewhere, he thinks.

As a teacher, Te Velde works for the Thomas More foundation, which aims to expose students to different religious traditions as part of their academic education. Although Wageningen University is fairly small, a relatively high number of Wageningen students find their way to the foundation. For Te Velde that is a sign that there is something missing. ‘Science is increasingly used in the service of society. Technical mastery and usefulness are everything nowadays. What this means for our humanity is a question that is no longer asked,’ he explains. Yuri Saris confirms this picture. He sees a trend comparable to that in the nineteen sixties, when a generation broke with the suffocating conventions of the day. Today again, there is a sense of loss of balance, says Saris. ‘Some students have the feeling that the government and the culture do not understand them. Something essential is being overlooked. Something in them is not being catered for. They do not rebel, but they embark on a quest for what they lack.’

BSc International Land and Water Management. Regularly spends time at Taizé, France.

‘When we went to France with the caravan, my parents used to take me to Taizé, but I still go back there now. The nice thing about Taizé is that you get to know people as soon as you arrive, and that you can really build relationships there in a week. You can speak all different languages and there is a very nice atmosphere. It feels uplifting to be there. Everyone seems to be at the same level and I think that is what makes it so easy to make contact. You often have very nice talks with people, and everyone is very open, partly because when you are there you suddenly have the chance to express what is going on inside you. I have had the experience that someone suddenly started to tell half their life story. When you stay there you just take part in the household of the monastic community, together with hundreds of other young people. For me it is really a place of refuge, a sort of recharging station, and sometimes I suddenly get the urge to go there. The world makes a lot more sense when I am there, and you can escape from your busy life for a while.

The music you sing at the services is inextricably associated with Taizé, which is really beautiful. Sometimes it sounds as though there are angelic voices among us. My parents tried to pass on to us the essence of all religions. I think there is more than one road to Rome, and all traditions have valuable rituals. People who come to Taizé are in search of faith, I think. Nothing is imposed on anyone, but something is offered. Something else I like at Taizé is that they pay attention there to interpreting the Bible. No explanation is imposed on you, but you do get the chance to discuss the stories you have heard in a small group. It is amazing to see how the stories mean different things to different people. They only become really meaningful when you can relate them to your own life.’

## Ieva Brigita (from Lithuania)

## Ieva Brigita (from Lithuania)

, MSc Leisure, Tourism and Environment. Sees storytelling as a way of gaining insight into her own life.

‘Taizé feels like home to me. I have never seen myself as religious, but every time I come back and hear the bells ringing, I get goose flesh. I was 16 when I went there for the first time. Like most teenagers, I was full of existential questions, but they melted like snow in the sun during my week there. Although you do have to stick to the rules, I feel free when I am there. You keep meeting friendly people. Such as Brother Hector, one of the hosts at Taizé. He told stories which made me feel they were meant especially for me. Gradually I have become interested in traditional ‘storytelling’. I recently attended a storytelling festival in Amsterdam to learn more about it. I was a bit sceptical at first, but eventually I was completely absorbed in the stories. I don’t know why, but at one point I couldn’t help crying. There were Canadian Indians, for instance, who told stories about their culture. They talked poetically about how humble behaviour is the most highly valued in their society. Unlike our society, where a modest attitude does not get you very far.

These kinds of stories give me a lot of food for thought, and that changes my outlook on many things. By showing how people deal with certain dilemmas or situations, they can give you insight into your own life. Many stories are passed on from one generation to the next, and are therefore not static but full of life. It is a very different thing to reading a story in a book. Listening to a story is something you do together, and yet you get your own feeling about it. For my Master’s thesis I would like to research how people look at stories and what role they can play in their lives. That is why I am going to India now: to listen to people’s traditional and personal stories there.’