If you are looking for flashy scientific solutions to the food shortages faced by hundreds of thousands of small farmers in Africa, don’t come to Ken Giller. The Wageningen professor of Plant Production Systems prefers to work with ‘off-the-shelf technology’. Through his partnerships with local and international organisations in the project N2Africa, Giller made sure that 252,000 small-scale farmers in eight African countries received packets of bean seeds, a bag of special artificial fertilizer and a bag of peat containing rhizobium bacteria, or inoculant. Giller calls these the ‘best bet technologies’: of the available knowledge and products, they stand the best chance of producing more food and money.

In this case, the bags of seed, fertilizer and bacteria generate an average of 335 dollars in additional annual income for the farmers. Giller works with legumes such as beans, cowpea, groundnut and soybean. The key benefit of these legumes is that they live in symbiosis with rhizobium bacteria, which fix nitrogen from the air. As a result, the plants need less fertilizer for a high yield. ‘We look for the best varieties of the legumes, the best bacteria to go with them, and the best management system for the farmer. The knowledge about that management comes from our farming systems analysis, in which we find out which business approach gets the best results per region and soil type.’

Ken Giller: ‘We look for the best varieties of the legumes, the best bacteria to go with them, and the best management system for the farmer.’

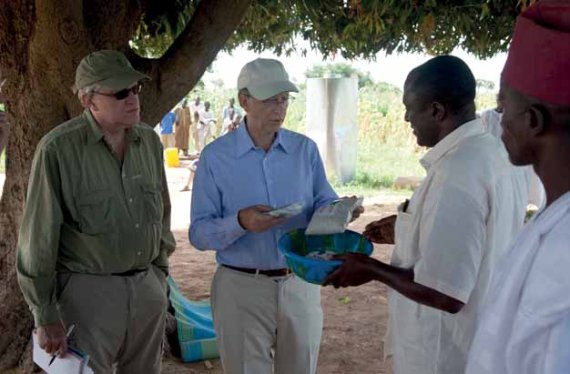

Four years ago, Giller’s concrete plan had already attracted the attention of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the organization through which Microsoft founder Bill Gates shares his billions with charities all around the world. N2Africa came in for 19 million dollars, and has maintained regular contact with the foundation since that time, says Giller. ‘I bring the Gates Foundation staff up to date at an annual meeting in Seattle, and I regularly meet them during their field visits to Africa as well.’ The researchers also make videos which keep the project on its chief donor’s radar, and on one occasion Bill Gates visited the project himself. Apparently, all these efforts have convincingly conveyed the value of N2Africa, because at the beginning of November it was announced that Gates is donating another 25 million to the project for the next five years. This is the biggest private donation ever made to a Wageningen project.

Women

Gates’s new contribution is sorely needed, because although the project has booked obvious results, there remains much work to be done. ‘The expectations of what the project would deliver have not been fulfilled everywhere,’ says Giller. N2Africa aims at raising production by 900 kilos of legumes per hectare, but in practice the average rise in production ranged from 270 kilos (for soya beans) to only 80 kilos (for peanuts). Giller is now looking for explanations for this uneven success. The team discovered one reason in Rwanda, where rich farmers got better harvests from their beans than poor farmers, even though they had received the same seed and fertilizer.

In the second phase linking farmers with markets will be the main activity

Richer farmers have more cattle and can use the manure to maintain the fertility of the soil. It also transpired that women got lower yields than men, which was because women carry out more household tasks, leaving them less time for tending to their bean field. ‘So here we need to find out whether less labourintensive technology is available for the women,’ says Giller. One fundamental limitation on the yields of small farmers, says Giller, is the very low soil fertility in many parts of Africa. Because over many years farmers have extracted more nutrients from the soil than they have added, they have ended up with very poor soils containing little organic matter and few micronutrients. Impoverished small farmers can only climb out of this poverty trap if they apply artificial fertilizer as well as crop waste and animal manure to their soils, says Giller. The project has therefore now come up with a special fertilizer for use on legumes. This fertilizer contains little to no nitrogen – which the bacteria fix – but above all phosphate, potassium and magnesium (see box).

Second phase

At the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Charlene McKoin is responsible for the N2Africa project. She is very impressed by the project. ‘In the first phase we found proof that nitrogen fixing by legumes can contribute a lot to soil fertility, increasing harvests and farmers’ incomes,’ she says over the phone from Seattle. To her, the fact that the objectives have not been reached is all the more reason to keep going. ‘There is still no solution for very poor soils when it doesn’t help to add bacteria. But the search for a solution to that will continue in the second phase.’

In that five-year phase, which the Gates Foundation will be funding to the tune of 25.3 million dollars, there will be a much stronger emphasis on marketing small farmers’ produce, says McKoin. ‘Farmers are quicker to embrace new technology if they can then earn more money from their product by selling it on new markets. Attention was already paid to this in the first phase, but in the second phase linking farmers with markets will be the main activity.’ Through N2Africa, farmers will also be able to improve their products, says McKoin, because they will get agricultural training. ‘That higher quality gives farmers access to new markets where they can earn more.’

Photo’s: Ken Giller