Wageningen lecturers are drowning in work. Work pressure and stress have increased enormously because of the coronavirus and there are hardly any silver linings. Three lecturers describe how they (almost) crashed. ‘I wanted to resign.’

‘You hear from teachers everywhere that it’s become busier,’ says Ute Sass-Klaassen. ‘More students are requesting guidance and because of the coronavirus crisis it all has to be done from behind a computer.’ Work has only got busier in recent months for the prize-winning lecturer in Forest Ecology and Forest Management who frequently makes the teacher of the year shortlist. Her inbox is overflowing with questions and requests for supervision.

‘I feel like I’m juggling ten balls at the same time. Sometimes I’m stretched past my limits. I always have to be doing something, I can’t sit still or take a moment to unwind. I don’t have enough time for reflection, it’s constantly full steam ahead. But I still feel I don’t have enough time for student supervisions. I taught very intensively for eight weeks in the first period. Afterwards there was a huge mountain of tasks and emails waiting for me. You really have to build in some down time after a period of teaching like that, but I can’t anymore. That has consequences for my private life: I don’t have much time for family and friends and I do everything in a rush.’

Kick

Sass-Klaassen knows she is on the edge, but she just is a very dedicated teacher. ‘I worry about the quality of education. The groups are getting bigger and I can see the distance between teachers and students growing. I know what good teaching looks like: a team of enthusiastic teachers who are experts in their field and can provide students with up-to-date knowledge and applicable skills. I love designing new courses, with excursions, enthusiastic guest lecturers, and practical sessions all falling into place like pieces of a puzzle. And I want to be able to teach in a certain atmosphere, with a group that forms a bond by the end of the course. Managing that gives me a real kick, but I have to do more and more to get that kick.’

I became a deadline junkie

When the going gets tough, she gets stressed easily. ‘The last few months we had trouble with the student registration system Osiris which made it difficult to find good internships for the students—I’m also the internship coordinator. When we heard that we had to change how we coordinate internships and theses, giving us even more work to do, that was the final straw. What use are emails thanking me for my efforts when at the same time they pull stunts like this!?’

Winging it

There is a clear pattern among the Wageningen teachers. They are motivated, want to deliver good teaching, and are now hitting the wall because they are doing too much. That is not just because the growing number of students means they have to do more supervision. It is also because of the coronavirus crisis, which meant they had to scramble together an online teaching system and now barely see their students.

Most the students’ feedback was positive, but I didn’t see it that way anymore.

Ronald Osinga, a lecturer in Marine Animal Ecology, was already suffering from stress and a high workload before the coronavirus crisis. ‘In our group, the number of thesis students has grown particularly fast. Last academic year I supervised at least 20 theses, a personal record. Supervising theses has become my core business. I can’t do any research acquisition or write my own articles anymore.’

Then came the lockdown. ‘I was in my bedroom recording all sorts of videos for my lectures. That cost a lot of time. You have to prepare them and sometimes you need three takes to get the recording right. I could see the piles of work growing. I was flying through all sorts of tasks, but I was winging it. Too often I found myself thinking: if we had discussed and thought through this student project more thoroughly we could have got more out of it.’

‘Our chair group tries to turn down as few students as possible, because we don’t want students to have to delay their graduation. But that demands a lot of creativity and produces a lot of extra work. The work piles up, though the workload does make you more efficient. I became a deadline junkie, but I reached a point where I couldn’t keep up anymore. That happened a few times in the past year. Around the summer holidays, that led me to conclude I don’t enjoy my work anymore. A startling realization because I’m 53 years old and it’s too soon to retire. What I want is to get back to the situation where I have enough time to do things well.’

The students felt alone, I felt alone

The last straw

Hannie van der Honing, a lecturer at the Laboratory for Cell Biology, also ran aground this year. Her stress levels had been rising in recent years too. First she put a lot of extra time into developing a course in English, then she worked long hours teaching after the introduction of the Extended Daytime Schedule, and then came the switch from Blackboard to Brightspace. And student numbers were growing the whole time.

The coronavirus crisis was the final straw. ‘In period 5, I taught a course for 235 students. Campus closed the Thursday before the course began. We had to switch very quickly to an online format. I spent days at the computer in my kitchen putting everything in Brightspace while trying to help my daughter with her schoolwork at the same time. Within ten days of lockdown I got such bad RSI I couldn’t slice a pizza.’

Van der Honing is a highly motivated teacher, so what did she do? ‘I switched to making videos, together with a colleague, for the online practicals. I would record the voiceover for the videos in WhatsApp and my colleague made films with the microscope. I also made quizzes and asked my husband to put them on Brightspace in the weekends, because I couldn’t do it myself anymore. The students were enthusiastic about the videos, which was very energizing.’

‘But after the exams I fell into a motivation slump. I had to teach another course in period 6 and I was dreading it. The microscopy practicals had to be done online for that course too, so I had to make videos again. But there was almost no live interaction with the students, and that affected me. Normally you can see if students are picking up the material and that gives me energy, but online you don’t get any impression of that. When students criticized the course I felt personally hurt. Most of the students actually gave positive feedback, but I didn’t see it that way. In retrospect I think that was a sign that I wasn’t doing well. The students felt alone, I felt alone, but this online Covid teaching was the only option.’

I’ve stopped working weekends

Resignation letter

She went on holiday, a lovely relaxing break. ‘But when I had to do a training course in my first week back on the new exam system ANS I started to panic: I don’t want to deal with this too! In period 1 I taught a course and the odd practical. I started getting panic attacks and I couldn’t sleep. Colleagues noticed the change in me and saw the tears welling up when they asked how I was doing. I thought to myself, I’m going to write my resignation letter. But then I thought: no, better to call in sick.’

Three months later, Van der Honing is still working and is sleeping well again. ‘I’m enjoying my work again, I don’t know why. Maybe it’s because of the contact with students. I’m now teaching three groups of 12 students and that’s fun, it gives me energy.’

She’s still dealing with an extra workload because of the Covid-19 rules. ‘In January we have a course for over 100 students. Normally we’d do the practicals in a big lecture hall. Now, because of the Covid-19 regulations, we have to offer each practical five times to smaller groups. We also have to put everything online, because students with colds have to be able to follow the practicals from home.’ But Van der Honing is taking better care of herself. ‘I’ve stopped working weekends and I regularly go running during the day. I’m only working four to six extra hours per week; I know colleagues who are working far longer hours.’

Succes

Ronald Osinga has also managed to get a handle on his situation. ‘We talked about potential solutions with the group. We’re taking on two additional lecturers. That will relieve some of the pressure. The new lecturers are starting now, which will allow me to clear my schedule and spend two months working on an EU proposal. This proposal came up unexpectedly, but it’s a huge opportunity. So, in consultation with my colleagues, I’m jettisoning my other tasks. It’s an enormous help to me; now I can focus on my own research for a while.’ Osinga is also going to start supervising PhD and Master’s students again, but far fewer than last year.

Ute Sass-Klaassen has not found a solution yet. ‘I like to do a variety of things, because I can incorporate all of those experiences in my teaching. I can’t muster the energy for projects like the Twitter tree, which I used to do in weekends. I would like to have a younger colleague working alongside me.’

Van der Honing heard the rector say that lecturers struggling with their workload might have to lower the quality of their teaching. ‘But Wageningen lecturers don’t want to do that. You have to go for quality, to help your students, even in these difficult times. It’s that high quality that gives me energy.’ But that quality is under pressure, says Ronald Osinga. ‘Student satisfaction is going down, because WUR’s strength is the high number of contact hours and those are now being squeezed. It’s nice that that WUR has been named the best university in the Netherlands for the 16th time, but in our group we sometimes say we’re the victims of our own success.’

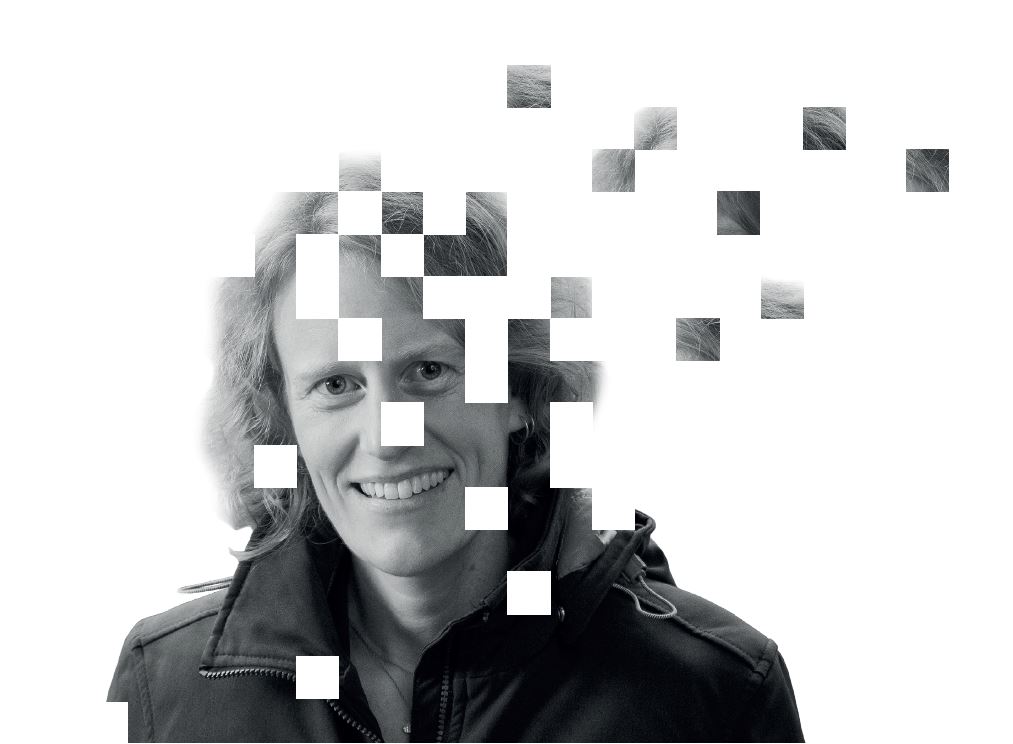

Teachers v.d Honing, Sass-Klaassen en Osinga. Photo: Guy Ackermans

Teachers v.d Honing, Sass-Klaassen en Osinga. Photo: Guy Ackermans