The Eastern Scheldt estuary was always teeming with them in the past. But last summer, for the fourth year in a row, there wasn’t an anchovy to be seen in the traps. Researcher Joey Volwater (Wageningen Marine Research) and student Robin Stark set out to find an explanation for this.

In the Netherlands, anchovies (Engraulis encrasicolus) are now only fished in one place by one family. The Van Dort family is all that’s left of the once flourishing Dutch anchovy fishing industry This was mainly located around the then Zuiderzee Bay, to which the tiny fish migrated in huge numbers in late spring to spawn. The construction of the Afsluitdijk causeway closing off the Zuiderzee about 100 years ago put paid to that, but the Eastern Scheldt remained accessible as a spawning ground. During the season, the Van Dorts caught around 8000 kilos of anchovies there every year, using the traditional method of weir fishing (see inset). That was until the summer of 2019. Since then, there have hardly been any anchovies in their traps.

Looking for an explanation, the Weir Fisheries Conservation Foundation came knocking at the door of Wageningen Marine Research (WMR). There was no funding but WMR did not want to leave the anchovy riddle unsolved. ‘Their question made our ecological hearts beat faster. After all, our surveys haven’t revealed a negative trend for the North Sea anchovy population. So why are they staying away from the Eastern Scheldt?’ says researcher Joey Volwater. He set up a student project to at least find out whether existing survey data offer any leads for an explanation.

List of suspects

And that’s how Robin Stark came on board. He’s a Master’s student of Marine Biology at the University of Amsterdam (Volwater’s call got no response from Wageningen). Among other things, he studied catch data from weir fisheries and correlated it with annual values of salinity and temperature. He also trawled through WMR fisheries surveys for relevant figures and insights. He made analyses and models and investigated the Van Dorts’ theory that Borssele offshore wind farm is to blame for the vanished anchovies. Or to be more precise, the wind farm’s power cables. It is since they went into use in 2019 that the anchovies have stayed away.

But Stark and Volwater soon took the wind farm off the list of suspects. Volwater: ‘Scientific research contradicts the fishing family’s hunch. Quite a lot of research is being done on the impact of the electromagnetic fields of those cables at present but so far, none of the studies have found a strong negative effect – not on fish species living on or just above the seabed, nor even on species such as sharks and rays, which have special receptors for electromagnetic fields. That makes it unlikely that anchovies would stay away for this reason, as they are pelagic fish living closer to the surface and have no such receptors.’

Delta Works

Volwater and Stark went down another route. Stark: ‘For anchovies, 14oC is a crucial threshold temperature for spawning migration. That temperature is reached a month earlier nowadays than it was around 1980. In some fish species, it has already been established that this can disrupt migration patterns, because the fish miss their cue to migrate in the runup to the spawning season. That could be a factor here too.’

There are some other systemic shifts that could explain the anchovy’s absence too. Volwater: ‘The Eastern Scheldt has always been an estuary, in which the water has a particular salinity gradient, warms up fast in spring and is relatively nutrient-rich thanks to nutrient deposition from the rivers. The Delta Works have changed that massively.’ The fact that the Eastern Scheldt has hardly any freshwater influx anymore has particularly far-reaching consequences – for salinity, nutrient balance, the temperature gradient over the seasons and water turbidity, for instance. ‘In fact, the Eastern Scheldt has been transformed from an estuary into a sea arm. A process like that is gradual, but there comes a moment when the tipping point is reached at which the area loses its appeal as a spawning ground. This assumption is supported by the fact that anchovies have not been found in the Eastern Scheldt since 2019, but are still abundant elsewhere in and near the North Sea.’

Scientifically, this explanation is not watertight, Volwater stresses. ‘In the Netherlands, anchovy is only fished at one location. The species has been virtually absent there for four years now, but we know nothing about anchovy stocks elsewhere around the Netherlands.’ Crucial comparative material is lacking on other fronts too. ‘There’s more research going on in France and Spain, where anchovy fishing has a much higher economic value. But the question is whether that knowledge is valid for “our” anchovies. Because we know from our research that the North Sea population is genetically different from the one in the Bay of Biscay. So they might not have the same triggers in terms of environmental variables such as temperature or salinity.’

Symbolic

Specific research would be needed to fully unravel the anchovy mystery, says Volwater. He holds out hope that there will be funding for that. ‘Our little report attracted quite a bit of media attention. Perhaps that will be decisive in nudging a government body or an NGO to release funds for it. Because it isn’t just about this one species, or about the last family still fishing for it. You could see anchovies as symbolic of all the changes in the Eastern Scheldt.’

Weir fishing

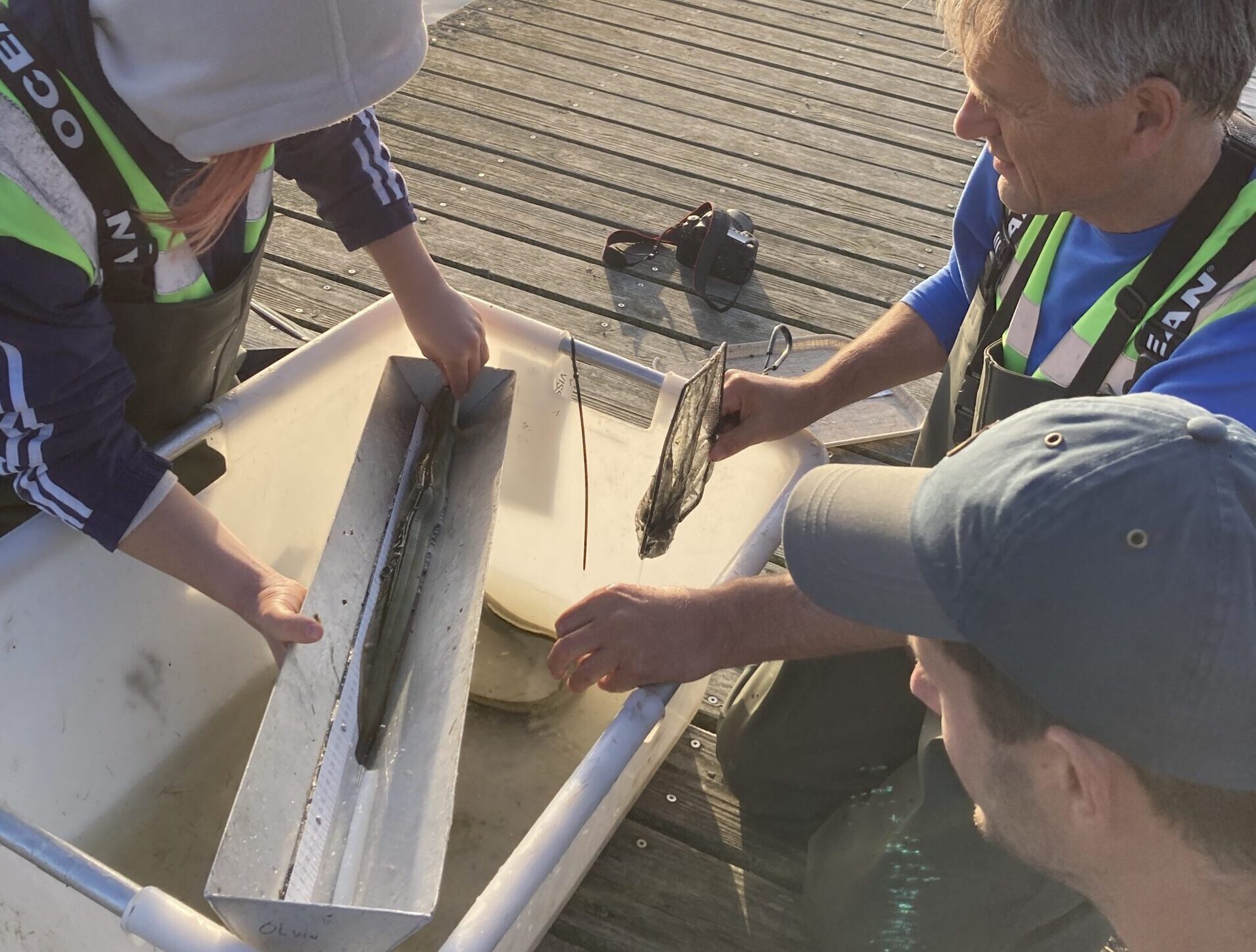

In this traditional fishing method, which has been declared cultural heritage in the Netherlands, fish are driven into a trap (a ‘weir’) when the tide is going out via a structure made of poles, making good use of the current. The method is quite sustainable, as after the target fish have been selected, bycatch can leave the trap unharmed.

Because of its considerable overbite, the anchovy is also known as ‘the Freddie Mercury of the fish world’. Photo Shutterstock

Because of its considerable overbite, the anchovy is also known as ‘the Freddie Mercury of the fish world’. Photo Shutterstock