The Wageningen historian concludes that the renowned Dutch polder model of consensus decision-making did not originate in the polders of Zeeland. The idea that local farmers joined forces in water boards to fight off the sea is not borne out by the evidence. Large parts of what is now Zeeland were covered by water in the Middle Ages, because the owners back then – local farmers, the church and the nobility – did not invest in dykes. The result was peaty soil with meagre yields. Many farmers left rather than struggle to ward off the sea. ‘80 percent of Zeeuws-Vlaanderen was submerged under water,’ says Van Cruyningen.

Indeed, there were countless floods in the 16th century. However, there was a plus side to this as the North Sea deposited fertile sea clay. ‘That happened very quickly. The land in Zeeland rose by half a metre of clay in only 30 years. The soil was so good for farming that investing in dykes became worthwhile.’

Backhander

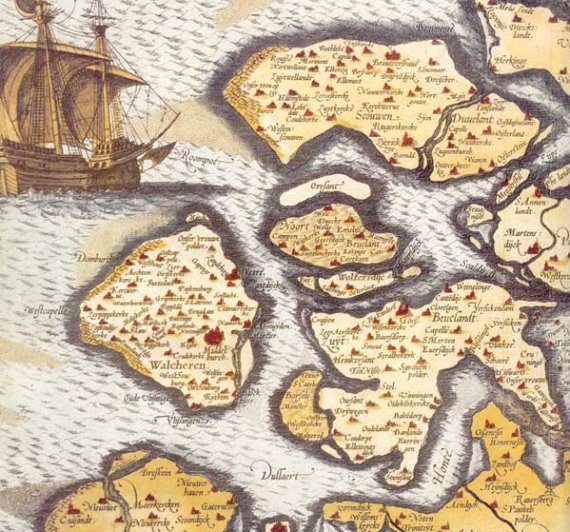

Dykes were erected and land reclaimed throughout Zeeland, apart from Walcheren which lay well above sea level. This was a gradual process as land reclamation was expensive: it cost 100,000 to reclaim 500 hectares. The farmers, church and nobility did not have that kind of cash, but there was lots of money in Middelburg, which supplied a quarter of the ships for the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC). The VOC merchants invested in land reclamation and were allocated part of the new polder in proportion to their investment. They then sold this land at a profit or leased it to ambitious farmers, who started growing wheat, barley, flax and madder on a large scale.

Van Cruyningen looked at ownership papers from the period and concludes that many merchants from Amsterdam and Rotterdam also invested in the new Zeeland polders, as did high-ranking civil servants in The Hague. ‘You had to get a permit to build dykes round a piece of land. I suspect the civil servants were involved in granting the permits and did so in exchange for a share in the new polder. It was a bit like giving a backhander.’

As land reclamation progressed, there were more and more conflicts, for example between the outermost polders that were responsible for maintaining the sea dykes and the innermost polders that benefited from this. The government responded with increasing regulation. Finally, at the end of the 18th century, the state took charge of dyke maintenance with the establishment of a special Directorate-General for Public Works.

Van Cruyningen says there was little consensus decision-making back then, even by the water boards. ‘The water boards weren’t democratic organizations. You needed at least 20 hectares to have the right to vote, for instance. The elites were in charge.’ But the historian says the polder model does have roots here. The water board governors did allow discussions between farmers and country people without voting rights, mainly to prevent and resolve conflicts.

Van Cruyningen works part-time in the Rural and Environmen-tal History group in Wageningen. He also works at the Huygens institute for Dutch history in The Hague. His research is part of a broader project within the Huygens Institute, looking at the origins of the polder model.