Thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) is used as a model plant in plant science. However, research by Wageningen and Utrecht shows many of the plants used in these studies have a virus. The discovery was a classic case of serendipity — finding something by accident.

The story begins about six years ago, explains René van der Vlugt, professor by special appointment of Ecological Plant Virology. When studying the genes for resistance to aphids in the plant Arabidopsis, Karen Kloth (Entomology) stumbled on something strange. ‘In some plants, 90 per cent of the genes that were expressed after an aphid attack were not Arabidopsis genes.’

Widespread

But what were they? Kloth asked Van der Vlugt. Could they be the genes of a virus? They did indeed turn out to belong to an unknown virus, one of the group of coronaviruses. Van der Vlugt asked Ava Verhoeven (who had just graduated and is now at Utrecht University) to investigate this further.

It soon transpired that Kloth’s thale cress plants were not the only ones to be infected with the virus: when the American database NCBI was screened, evidence for the virus was found in a quarter of the 6500 Arabidopsis datasets. The virus is widespread in laboratories around the world, and also in wild thale cress. But it does not make the plant ill. Infected thale cress plants do not show any symptoms of disease.

Repeat

So there is a virus and it is infectious. Does that mean all the studies of Arabidopsis are now worthless? Van der Vlugt: ‘That would be going too far. Some of the research focuses on the influence of pathogens, including viruses, on gene expression. If a plant had this newly discovered virus, that might have affected the outcome, so you should really repeat that study.’

It seems the plant and the virus have coexisted for a very long time

René van der Vlugt, professor by special appointment of Ecological Plant Virology

An intriguing question is why the plant makes this viral material, and on such a large scale in some cases. ‘From a scientific perspective, that is the biggest question for me,’ says Van der Vlugt. ‘In some of the plants, the virus suddenly mushrooms. Is that triggered by something? Is it random chance? That’s unlikely; there must be a biological effect operating as it costs the plant a lot of energy to multiply the viral genetic material in such large numbers.’

Coexist

Some of the research was carried out at Utrecht. Verhoeven discovered there that the virus does not fundamentally change the gene expression of the thale cress. Van der Vlugt says this suggests the plant and the virus have coexisted for a very long time. That is also evident from the high degree of transferability of the virus via the plant’s seed. The virus is present in 40 per cent of the plant’s offspring, which is far more than for other viruses.

Another discovery was made in Utrecht: the virus makes thale cress slightly less sensitive to drought. The effect is small but significant.

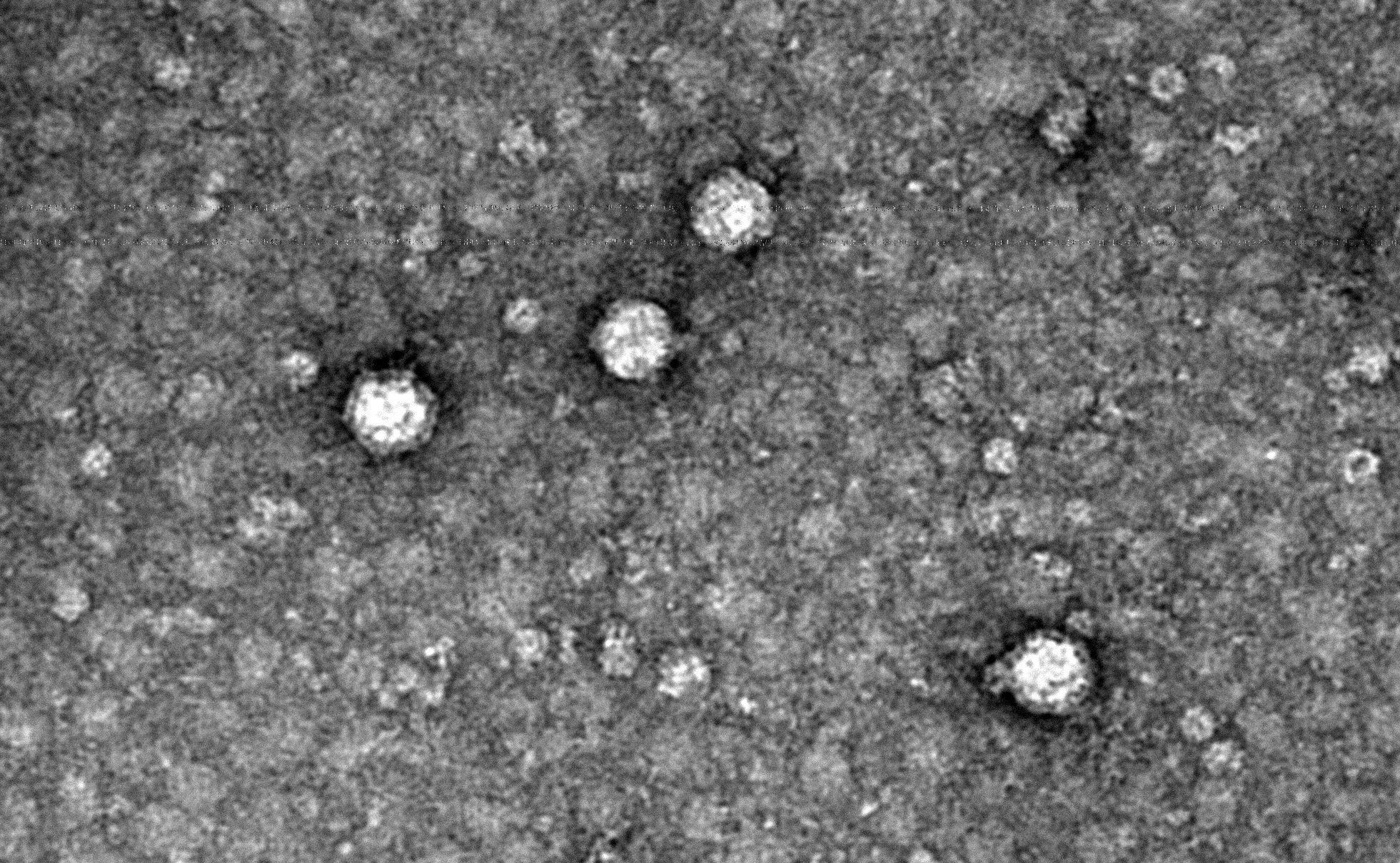

An image taken by an electron microscope shows virus particles in an infected thale cress. The image has been magnified 100,000 times. The particles are 28 nanometres in diameter. Photo Biointeractions & Plant Health

An image taken by an electron microscope shows virus particles in an infected thale cress. The image has been magnified 100,000 times. The particles are 28 nanometres in diameter. Photo Biointeractions & Plant Health