Researchers at WUR have developed a process for printing a vegetarian burger. The burger is made up of spaghetti-like threads of protein.

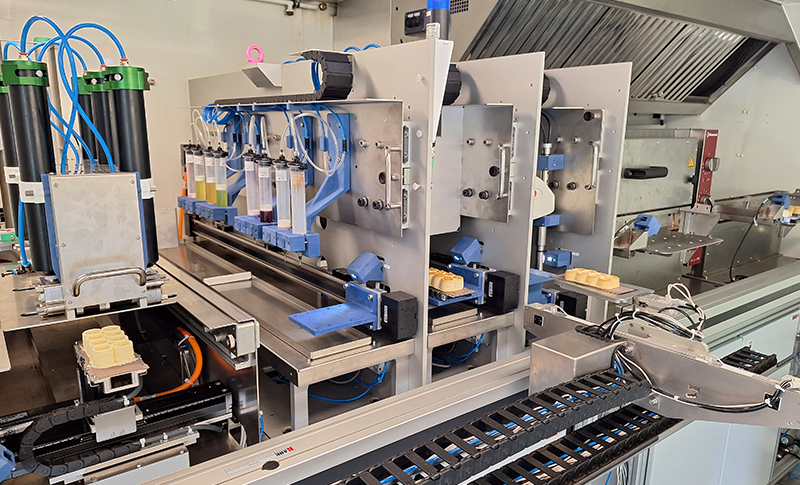

In the process hall of the Axis campus building stands BEP. Or Beppie, as the machine is affectionately called in the workplace. The abbreviation stands for Burger Extrusion Printer, one of the first of its kind in the world. This fulfils the wish of an anonymous donor who gave WUR one million euros to develop the machine nearly two years ago. The generous donor’s assignment was clear: design a 3D printer that can make a meat substitute out of plant protein.

And can Beppie do that? A cautious ‘yes’ is the answer from project leader Laurice Pouvreau. ‘We have made progress insofar as we can make fibrous structures from plant based material with a 3D printer. And from these fibrous structures we can make threads with which shapes can be printed.’ And yes, it has really been used to print a burger. But it is not as though the printer has already gone into mass production of veggie burgers in the process hall. In fact, Beppie is currently unemployed and waiting for some follow-up. The private funding is finished and a proposal for a follow-up is waiting for the green light. Pouvreau believes there is every reason to take the project further.

Biefstuk Bali 0.0

WUR was not the first past the post, though. That was the Israeli company Redefine Meat, which made a splash with the first cuts of printed meat last year. Recently, their product has been on the menu at several branches of the Dutch restaurant chain Loetje (including Arnhem) under the name Biefstuk Bali 0.0. Animal-free meat, hence the 0.0.

Veggie burgers are an intermediate step: they look like something the consumer is familiar with

How Redefine Meat makes the meat is not clear. More is known about the Wageningen approach, although details are withheld because of patent applications in progress. But Pouvreau explains that the basic steps are comparable with techniques such as extrusion and shear cell technology (a process from Wageningen) for making fibrous structures from vegetable protein. ‘It is a combination of heating and cooling,’ Pouvreau explains. ‘You have to heat the material to unfold the proteins and create the fibrous structure. Then you have to cool it down to fixate that structure. What we have fine-tuned is the time the material spends being heated and cooled, which is less than a minute in our process. That is very short compared to an extruder (three to five minutes) or a shear cell (up to 20 minutes).’

So far, the printer has mainly been working with bean protein ingredients. Bean protein isolate, beans in processed form, is the raw material that goes into the printer. It is then pushed under pressure through a narrow tube of a few millimetres in diameter, heated and cooled. This process produces printable threads. Pressure and temperature have to be adjusted very precisely, says Pouvreau. ‘You have to strike a balance between printability and the right bite and flavour.’ As far as flavour is concerned, the printing process has a surprise up its sleeve. What comes out of the printer turned out to taste a lot better than expected. Pouvreau: ‘Beans that come out of an extruder do not taste very nice, without addition of flavour. Post-processing is needed to make palatable meat alternatives. With our printer, that is not necessary; you don’t get much of a beany taste.’

Crucial

It’s not entirely clear yet why the printing process improves the flavour. ‘It probably has something to do with heat transfer and short residence time’, says Pouvreau. ‘We push the protein through a very narrow tube. That ensures efficient heat transfer so the fibrous structure is created in a short period of time. How a product tastes is closely related to its texture. The texture we create is probably different from what an extruder delivers thanks to that short heating time.’

Actually, I want to get away from the idea that the end product must taste like meat

Crucial factors for the flavour of meat are its bite and its juiciness. Existing veggie burgers are often no match for meat when it comes to these qualities. Beppie’s solution to that lies in a ‘coaxial’ printing method. ‘That means we insert the juice into the printing thread,’ explains Pouvreau. ‘In effect, we print two things at once: a firm exterior resulting in the bite experience, based on protein, and a soft interior, based on an emulsion. This makes the product juicier and more appetizing once it is cooked, so it is more like beef and pork. If you cut into the thread, you can see the emulsion. It looks like spaghetti with a filling inside it.’

Intermediate step

It is this last development in particular that Pouvreau and her colleagues are keen to research further with new funding. And as far as she is concerned, the development should not stop with vegetarian burgers that imitate meat. ‘Actually, I want to get away from the idea that the end product must taste like meat. It should taste like something plant-based. Plant protein is different from animal protein, so why would we want to simulate that? But it will take some time to convince consumers that plant-based products are good by themselves. It will need a new generation. Veggie burgers are an intermediate step: they look like something the consumer is familiar with. Hopefully we can then move on to plant-based food with a niche of its own on the market’.

Photo Eric Scholten

Photo Eric Scholten