The theme of the upcoming opening of the academic year is Planetary Boundaries. We are crossing more and more of our planet’s boundaries. And yet all hope is not lost, says Professor Marten Scheffer, one of the speakers at the opening.

Heat, drought and floods are turning into almost everyday phenomena. This year’s hot summer might prove the coolest of the coming decades. So it’s no wonder that the opening of this academic year will focus on the boundaries of planet Earth. These boundaries guarantee stable living conditions, provided they are maintained. The term ‘planetary boundaries’ has Wageningen roots, actually. Marten Scheffer, Professor of Aquatic Ecology, was co-author of the 2009 article in Nature that coined the term.

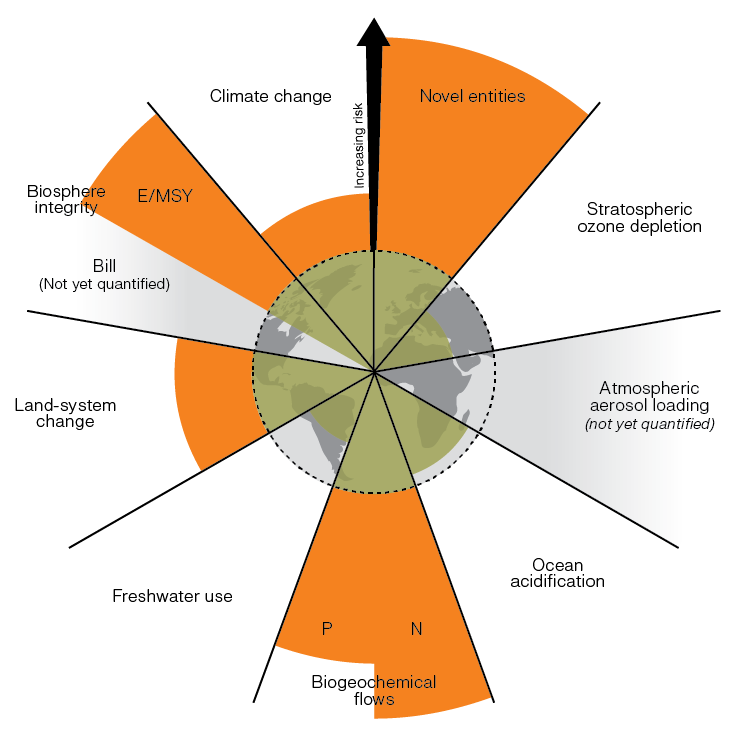

In the paper, ‘A safe operating space for humanity’, a group of international scientists led by the Swede Johan Rockström set out the boundaries we must not exceed in nine essential subsystems of the Earth’s system. These include the amount of CO2 in the air, the rate of decline of biodiversity and the acidity of the oceans. Within these nine boundaries, it is safe to live on earth. Beyond them, we enter an unsafe, uncertain and possibly catastrophic future. The message was condensed into a crystal-clear graphic depicting the boundaries for all to see (see illustration). At the time, the boundaries were already being crossed in three areas: the loss of biodiversity, CO2 levels in the air and the disruption of the nitrogen cycle.

6244 citations

The paper hit home. ‘This one had and is still having a huge impact,’ says Scheffer. The count on Scopus, the search engine for scientific articles, is currently at 6244 citations. In Scheffer’s own extensive oeuvre, it is the most cited work by far. ‘Why has it been such a success? I think because it is written from a positive perspective,’ says Scheffer. ‘A safe space for humanity is a very appealing prospect. With that starting point, you don’t frame it in terms of dangerous boundaries that you mustn’t cross. Instead, it works the other way round: so far, so safe.’

It was Rockstrom who took the initiative for the article. ‘He wanted a clear image, a visual aid for a clear story, which would be inspiring and supportive for the pursuit of sustainability in politics. To this end, he invited a number of people to contribute. My British colleague Tim Lenton and I came onboard as representatives of the idea of tipping points, the critical boundaries of the climate. But you can’t pinpoint such global tipping points precisely. You don’t know for sure if there is one, and if there is one, where exactly it is. There is uncertainty. The safe operating space referred to in the article demarcates this uncertainty. It is the space you have to stay in. Beyond it there is uncertainty and dangerous things can happen’.

We know perfectly well what we need to do, but we don’t do it

The 2009 success story did not end there. The Stockholm Resilience Centre updates the data annually and, with minor adjustments, the concept still holds true. But more than a decade down the line, the picture is no rosier. The latest graphic shows that we have now crossed five of the nine safe boundaries. In terms of pollution and land use, too, we have arrived in terra incognita, according to the researchers. Only the use of fresh water, the acidity of the oceans, the ozone layer and the level of aerosols in the air remain within the safe limit.

Decline

‘The more we know, the more we see that the subsystems of the planet we depend on are in worse shape than we thought,’ Scheffer responds. ‘That they are more fragile than we realized. On the whole, sadly, things are not going in the right direction. There are occasional small improvements, such as when a species adapts better than we expected. But the overall picture we get is that the climate and biodiversity are deteriorating. The more we understand the system, the more we see that it is more precarious than we realized.’

The decline seems unstoppable. And that is not because we do not understand the climate system or nature. Scheffer: ‘In general, we know perfectly well what we need to do. What should be done about climate change? Leave the fossil fuels in the ground. How do you reduce the loss of biodiversity? Keep your hands off nature. Or, in practical terms: eat less meat. We know it, but we don’t do it. I am a biologist, but recently I have noticed that I am studying humans more and more. Not just because people are interesting, but also to understand where the problem lies. Why we can’t manage to do the right thing.’

Darker scenarios

That we and the planet are entering uncharted territory is now certain. The comforting prospect of a safe space is increasingly out of reach. It is therefore high time we explored the perilous world on the other side of the boundary. This is the appeal made by Scheffer and an international group of colleagues (including five co-authors of the 2009 paper) in an article published in PNAS this summer. The piece has the ominous title ‘Climate Endgame: Exploring catastrophic climate change scenarios’.

So has defeatism set in, now that the safe space is fast disappearing from view? ‘No,’ says Scheffer, ‘I don’t think so. Our main message is to point out that scientists systematically underplay negative scenarios for fear of being called prophets of doom. We can still limit the damage by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. But we must also prepare for darker scenarios. Even if we succeed in keeping global warming below two degrees, which is unlikely by the way, there will still be a lot of consequences we shall have to address.’

We will have to prepare for a darker scenario

‘Our plea is to study these consequences as a whole. Not just to look at the direct effects of climate change on crops or people, but also to look at indirect effects, such as the emergence of uncontrolled migration or armed conflicts. And take a look at the way things can all happen at once: droughts that occur in different places at the same time, a hurricane that knocks out the electricity so that the air conditioning no longer works, just when there is a heat wave that pushes urban temperatures up to 50 degrees. All sorts of things can happen and they don’t come entirely out of the blue. At present that is still the stuff of popular science writing. Our plea is that we scientists must provide the most reliable possible information on these things and stop evading the issue’.

Hope

Facing up to a ‘climate endgame’ or ‘worst-case warming’ doesn’t sound a very hopeful prospect. ‘And yet there is reason for hope,’ says Scheffer. ‘Something is brewing. It may seem as if nothing is changing, but that is what you see when you are approaching a tipping point too. I think that in various ways there is something brewing in society. There is a growing awareness that things are heading in the wrong direction. And people are fervently looking for ways to do something about it.’

According to Scheffer, WUR plays an important role as a guide in this process. ‘If you want to change society for the better, if you want to get humanity to change direction, you not only have to know what is wrong, but also to show what is possible, where we could be heading. WUR must develop that narrative. Technological solutions alone are no longer enough. It is also a question of things like building with nature, systemic change in our food production, identifying barriers in the way society thinks.’

It could turn out well or it could go wrong. It’s up to us

According to Scheffer, Wageningen is clearly shifting in that direction. ‘And we are an incredible powerhouse. Including our students, for sure. I am often so impressed by how well students think about and work on these things. This is an important moment in human history and we can play an important role in it. It could turn out well or it could go wrong. It’s up to us. It’s our call.’

Marten Scheffer: ‘The more we know, the more we see that the planet is in worse shape than we thought.’ Photo Shutterstock

Marten Scheffer: ‘The more we know, the more we see that the planet is in worse shape than we thought.’ Photo Shutterstock