Not all consumers are aware of the healthiness of food products. Policies to label the nutritional quality of products can help increase that awareness and change consumer behaviour for the better. A new study discovered that in response to such change, retailers increase the prices of unhealthy foods.

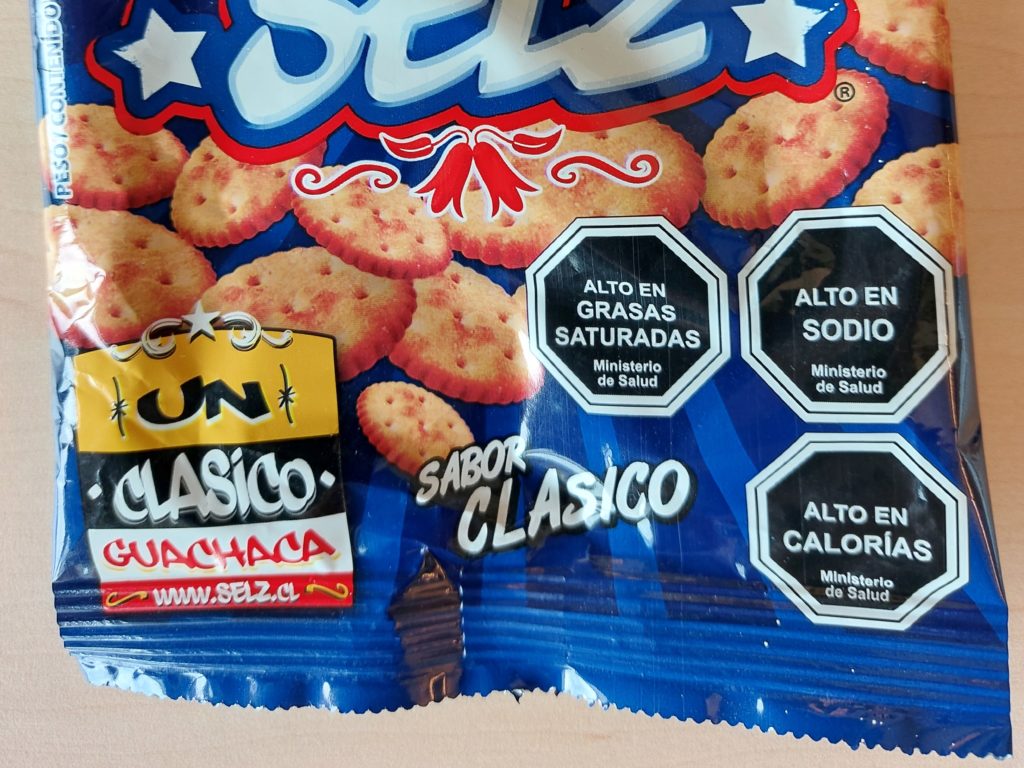

Chile was the first country to adopt mandatory nutrition warning labels on all food products in 2016. The labels warn about too much sugar, salt, or fat in a product. Researchers of WUR, Tilburg University, and KU Leuven were surprised to find that these labels led to increased prices of unhealthy foods. They published their results in the Journal of Marketing Research.

Predict prices

‘With warning labels, you expect prices for products that carry the label to drop because of lower demand,’ says Erica van Herpen, associate professor at Marketing and Consumer Behaviour group. ‘It did not work that way: prices went up.’ The researchers built a model to understand and predict such price changes. The model used data from 2,660 households to infer changes in purchase behaviour before and after the introduction of the labels. Based on these changes, the research team then predicted the price responses of retailers.

‘It is important for policymakers to know the effects of nutrition labels on food prices in advance because it determines whether the policy is effective,’ says Max Pachali, assistant professor in Marketing at Tilburg University and the first author of the study. ‘If warning labels lead to lower prices for products with the label, consumers may actually buy more unhealthy products.’

Awareness

In Chile, prices of labelled products increased right after the introduction of the labels and then stabilised within two years. This happened because price-sensitive consumers changed their behaviour. ‘Price-sensitive households respond more negatively to the warning labels,’ says Pachali. In other words, they avoided buying labelled, unhealthy products. Van Herpen adds: ‘People who are more price-sensitive might also have a lower income, lower education and may be less aware of the unhealthiness of some products.’ The warning labels gave them clear and new information on the unhealthy consequences of their consumption and enabled them to make healthier choices.

Compared to the situation before regulation, the labelled products were bought more by consumers who care little about prices, so retailers could take advantage and increase their prices. ‘Price-insensitive consumers are usually more educated and already know more about nutritional facts. They are aware of their unhealthy consumption,’ explains Pachali. ‘Therefore, they didn’t change their behaviour.’

Nutri-Score

Other Latin American countries followed the example of Chile, introducing mandatory warning labels. It is too early to say if the labels have the same effect there. The European Union does not consider the warning labels but aims to adopt the Nutri-Score. This score rates the healthiness of food products from A (healthiest) to E (least healthy). It is already used in the Netherlands but voluntarily. ‘That is an important difference,’ says Pachali. ‘If it is not mandatory, you get self-selection: companies choose to label their products only if they think it benefits them.’

Besides, warning labels may be more effective in changing consumer behaviour. ‘A meta-analysis by Iina Ikonen of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam suggests that,’ says Van Herpen, ‘but this type of label is relatively new – we know less about them than other labels.’ Max Pachali sees another advantage of the warning labels over Nutri-Score: ‘The warnings are easy to understand. Nutri-Score rates from A to E. It is not clear if it is bad for you. The labels will only work if they give new and clear information to consumers.’

Waarschuwingslabels kunnen consumenten helpen gezonde keuzes te maken. Foto Shutterstock.

Waarschuwingslabels kunnen consumenten helpen gezonde keuzes te maken. Foto Shutterstock.