On behalf of the occupiers, Theun Vellinga hands over the Black and White Book with suggestions for educational improvements. © Archive WUR and Guy Ackermans‘This is where the banners were painted,’ says Janny van Gijssel during our guided tour of Villa Arion. The door swings open on a basement room with a floor covered in stripes of paint. A witness to half a century of activism.

From 1969 to 2012, this stately house on the Niemeijerstraat in Wageningen town centre was the headquarters of student union WSO. Van Gijssel and her husband bought the run-down premises from WUR six years ago. The walls were still covered in layers of posters proclaiming forgotten political ideals. Arion is now a beautiful home, B&B and cookery studio. In spite of this metamorphosis, Mona Commandeur can still picture the old setup: ‘There was the accommodation office and the job centre, there was the sales point for readers and stationery,’ she points out. ‘And in the basement was the stencil machine; there were no photocopiers in those days.’

Mona Commandeur in the living room of the renovated Villa Arion, once the headquarters of student union WSO.

Knitting

In the spring of 1980, Commandeur, nowadays a freelance consultant and project manager in the agriculture sector, was a student of Animal Husbandry at the then Agricultural College, and chair of the student union WSO. She was famous for the knitting she took along to meetings – ‘it helps me to listen well,’ she says. But the time for listening was over on 5 March, when Commandeur stuck her foot in the door of the college headquarters on the Salverdaplein, thereby kicking off the Wageningen Spring, an occupation that would go on for four weeks (see inset).

To conjure up memories of the protest, we are allowed to use Van Gijssel’s living room in Arion, once the meeting room where the WSO’s many protests took shape. They followed a fixed pattern in those days: a few dozen students would form a demonstration committee that would set off for the faculty or administration building and block the entrances there. What would follow were demands, negotiations, rhetoric and after some hours, or perhaps a night, the occupation would be over. And if it hadn’t achieved enough? Then planning started on the next protest straightaway.

Massive turnout

But at the beginning of March 1980, events took a different turn. The turnout at the meeting to plan the protest against the two-phase degree structure (see inset) was not the usual few tens but 800 to 900 students. The night before, in Kafé Troost, the old guard of the union had agreed to cancel the occupation if there were less than 60 people. The massive turnout took them completely by surprise.

The demonstrators meet with the Executive Board of the Agricultural College on day one of the occupation.

The vast majority of those present voted for an occupation, after which 400 students marched to the Salverdaplein and took over the central wing of the building. ‘It was a complete surprise there too,’ says Commandeur. ‘Staff walked outside as if it was a fire drill. Personal effects and dossiers were lying open and exposed on the desks. Quick as a flash, my fellow board member Theun Vellinga stuffed everything into drawers and cupboards, and locked them.’

The reason why so many students were prepared to take to the barricades, says Commandeur, was the cultural shift that had taken place in the WSO in the previous years. In 1979, she found a union with the knowledge, experience and infrastructure to organize protests, but also one with a dwindling support base. Only one in three students belonged to the union, half the proportion at the beginning of the 1970s. ‘There was no life in Arion; the spark was gone,’ says the former union president.

| De Wageningen Spring | ||

|---|---|---|

| In 5 March 1980, 400 students occupied the administrative headquarters of the Agricultural College on the Salverdaplein, to express their dissatisfaction with the cutbacks planned by the minister of Education, as well as with Wageningen education. Minister Pais wanted to introduce the two-phase structure into higher education and limit the time you could spend in higher education – at that point unlimited – to six years. Students all over the Netherlands were up in arms about this, but in Wageningen there was mass resistance. This was because the students at the Agricultural College had long been campaigning for educational innovation, and they were afraid it would now come to nothing. They wanted their education to be more relevant to professional practice and societal issues. That would require more project-based education, more interdisciplinary integration and more attention to the social sciences. When the riot police ended the occupation after four weeks, the protesters had not actually achieved anything. Nevertheless, the Wageningen Spring – a reference to the Prague Spring of 1968 – gained a sort of cult status. That respect was due to its unusual length and its impact: the occupation was the prelude to the creation of the typical Wageningen education system, with a lot of freedom of choice and project-based education. |

Leftwing goings-on

The trilogy History of the Agricultural College paints a picture of the WSO as a sectarian, Marxist bastion where mainly older male students – diehard union members – called the tune. They maintained close links with far left political parties such as the communist CPN, the socialist PSP and the then still Maoist SP. Taking the political union approach, the WSO focused mainly on lobbying on material issues of funding and housing, solidarity with future students (against recruitment caps) and support for developing countries. Concern about the environment was starting to play a role too.

Mona Commandeur (left, with papers)

Mona Commandeur (left, with papers)

attends a meeting together with other demonstrators.

Democracy was nowhere to be seen in the WSO, says Commandeur. In the highest consultative body, the Policy Council, sat representatives of the 22 subject groups: students who were active in the degree programmes. ‘They were trained by the older WSO members to form a new cadre. In practice, the WSO saw these delegates less as representatives than as the union’s advanced guard,’ says Commandeur. ‘That led to friction and mistrust among the subject groups, not least because the WSO took very little interest in the content of the education. In Livestock, for instance, we had a very active subject group, critical about the education but pragmatic too. The people there didn’t think much of all the leftwing goings-on at the WSO.’ Black and white bookCommandeur first moved into Arion in 1979. ‘When Theun Vellinga and I were asked to be on the board – they couldn’t find anyone else – we went to a squat in Amsterdam to figure out a new setup. We wanted a union that listened. Then we visited all the subject groups to hear what their concerns were. And we heard a litany of complaints about the lack of educational innovation. Then I said to the old guard: ‘Guys, we are going to put that lobbying on material issues on hold for the time being. Start studying again please, we don’t need you for now; we need to build up a new support base. We got no thanks for that. We even dropped the traditional, annual disruption of the opening of the academic year, where the police lined up ready beforehand.’

Sleeping occupiers in the administration building.

Commandeur and Vellinga (now a researcher at Wageningen Livestock Research) succeeded in mobilizing new allies: students who were actively involved in the college and faculty boards, departmental education committees and subject groups, as well as in organizations such as Agromisa and the Boerengroep. That collaboration resulted in a ‘Black and White Book’ opposing the proposed two-phased system and offering criticisms and suggestions for more ‘problem-centred, socially relevant education’. Commandeur: ‘All the signatories to the wishes expressed in the Black and White Book got a copy, but they had to pay a guilder for it because we were very short of money. In the end 1000 were sold, many of them to members of staff. That boosted our conviction that we were on the right track.’ Education fair That spring, the occupied administration building was the melting pot in which the occupiers – stressing that there were now women among their numbers – developed the ideas in the Black and White Book. They came up with 70 specific proposals for project-based education. These were presented at the end of March during a sun-drenched education fair on the square outside the occupied building. On the front of the building hung a banner proclaiming ‘The Wageningen Spring’. And that has been the protest’s nickname ever since, although the reference to the Prague Spring proved provocative. Commandeur: ‘That was sensitive in the Executive Board. Board member Wouter Douma was sorely offended that the college board appeared to be equated with Russian aggression against freedom fighters in Czechoslovakia.’

Of the 70 education projects presented at the fair, 50 were actually implemented, says Commandeur. ‘That also means that many members of staff felt involved too, otherwise no supervision would have been possible.’ According to Commandeur, there was a lot of passive support in Wageningen. ‘Even students who were against occupations as a means of protest mostly supported the call for educational innovation. What contributed to that was the worry that the two-phase structure would put an end to the element of practical experience in the education programmes. The protest stimulated Wageningen-wide discussion. By the time the building was cleared, innovation was inevitable.’ Divisions One thing the Wageningen Spring lacked was a happy ending. Peter van de Schans, then chair of the Executive Board, adhered to the motto: no police on campus. He therefore negotiated with ‘his’ students for weeks. The board understood the wish for educational innovation and the opposition to the budget cuts planned by minister of Education Pais (see inset), but could not undertake to ignore decisions taken in The Hague. Despite the efforts of several mediators, it was impossible to reach a compromise.

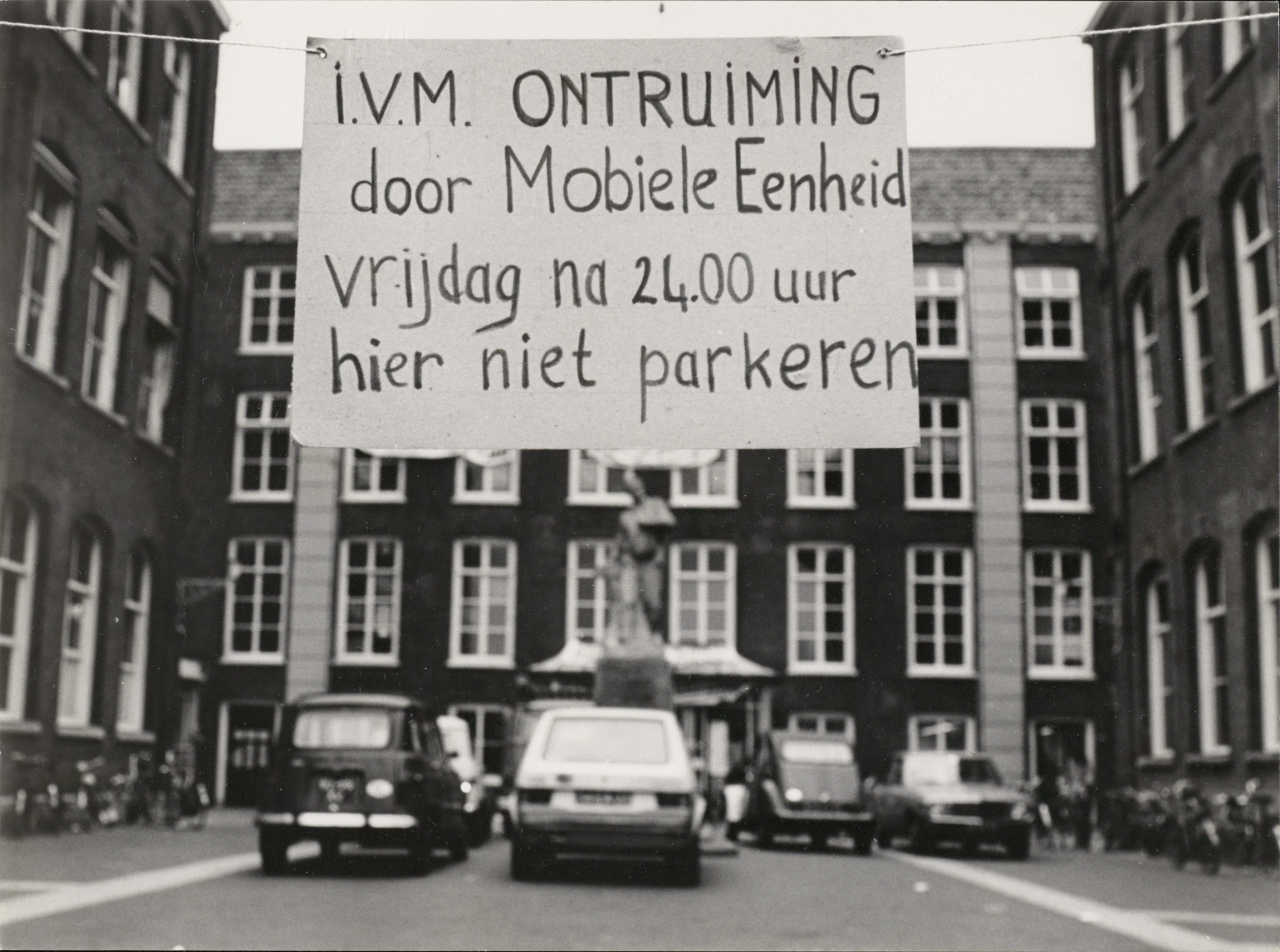

A handwritten notice announces the end of the occupation.

According to Commandeur, this was because students were divided amongst themselves. ‘On one side there were the education people who wanted to give up the occupation after the success of the education fair. On the other side were the radical members who focused mainly on fighting the cabinet plans. Much to their disappointment, they could not prevail in the biggest student protest Wageningen has ever seen. Nor had they achieved any results yet, either. Due to these divisions, the decision was taken not to leave the building of their own accord.’

Headstart

Eventually, enough was enough. Salaries needed paying, staff were grumbling and some of the students said they were fed up with the occupation. The end came at 7:30 in the morning on Monday 1 April. The police forced their way into the building and the 200 occupiers – specially drummed up, as the night before there were only 20 students left – left without resistance. They hadn’t achieved much: minister Païs pushed through his budget cuts and dismissed the occupation as an ‘outdated ritual’. But even on the day the occupation ended, the far from bitter Executive Board wanted to talk about education, which led to a broader discussion on the topic. ‘Wageningen got a headstart on other academic institutions,’ says Commandeur. ‘A later rector, Cees Oosterlee went so far as to say: ‘Wageningen had thoroughly overhauled its education, with freedom of choice, social relevance and a range of teaching methods, while elsewhere in the Netherlands that process was still in its infancy.’