Text Tessa Louwerens Illustration Birgit Boogaard

‘It is a tremendous gesture of recognition for this relatively new discipline at WUR, Boogaard tells me on Skype. Behind her hangs a cloth with an African print on it from Mozambique. ‘I usually use that in lectures, but now it is handy for keeping stuff in.’

Boogaard has spent a lot of time in Africa herself, including two years living in Mozambique, where she did her postdoc. She takes her experience of Africa into the classroom with her. ‘It is important to realize that we think and see the world from a European perspective.’ For many students, that is an eye-opener. ‘I tell my students about our project in Mozambique, and get them thinking about it. In what ways was my thinking there Eurocentric?’

Assumptions

In Mozambique, Boogaard worked on a development project for goat farmers. ‘We helped them increase their production and generate more income. We got goat farmers involved and asked what their priorities were.’ But Boogaards didn’t ask the crucial question: what does development mean to these people? Is it only economic development? ‘The concept “development” incorporates the assumption that Africa is backward and that people there need help to get to our Western level.’ This Eurocentric thinking is problematic, says Boogaards, without judging anyone. ‘This is how we have been brought up and educated. We do things with the ‘best of intentions’, often in ignorance. The thing is to become aware of it.’

World view

Boogaard wants her course to open up another world view. ‘When I was a student, I would have loved to have had this awareness before I went to Africa. I had very open discussions with goat farmers but I still felt I was missing something. When I got back to the Netherlands I happened to get talking to intercultural philosopher Heinz Kimmerle (1930-2016), who has written a lot about Eurocentrism in philosophy. It was from him that I first heard about African philosophy. That’s when the penny dropped.’

In Mozambique, Boogaard did research on the role of goats in the community. ‘People talked about their ancestors, and I understood that they played an important role, but couldn’t exactly put my finger on it.’ Through African philosophy, she learned that an African community consists not only of the living but also of the living dead – usually called ancestors – and the yet unborn.

‘This invisible world is often hard to understand from a Western perspective, and was wrongly seen by colonialists as inferior and primitive. But a better understanding of it gives us deeper insight into things like people’s relationship with nature and the sustainable use of natural resources. You thank your ancestors for leaving you the land, and you make sure you leave it in good condition for the generations that come after you. That is something we in the West could learn from, instead of saying these farmers are not commercially minded enough and we will help them increase production.’

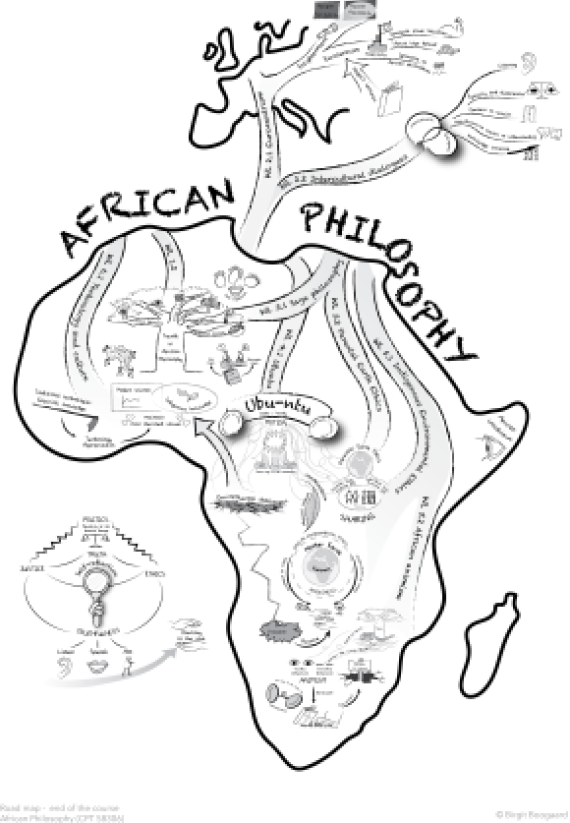

This was how Boogaard hit upon the idea of launching an elective course on African Philosophy at WUR in 2018. ‘We need this perspective. Especially in the international context WUR is working in. It teaches you to look through a different lens at the big issues surrounding WUR topics such as the food supply, nature conservation and the environment.’

Relationship

Boogaard emphasizes that the course is an introduction to African philosophy. ‘Africa is vast and diverse, and that applies to philosophy there as well. We touch on a few subjects, such as Ubuntu, an important philosophy that has spread all over Africa. One saying in Ubuntu philosophy is Umuntu ngumuntu ngabantu in Zulu. Roughly translated, it means: A person is a person thanks to other people, or: I am because we are. Boogaard: ‘It assumes that your humanity is confirmed in relationship with other people.’ She seeks to create that sense of relationship in her classroom as well. ‘We don’t just study the philosophy: I want the students to experience it too. The basis for a respectful dialogue is listen without judgement.’ To practise that, the students interviewed each other about their points of view. ‘They practise with the aim of not just understanding what the other person is saying rationally, but also really seeing the other with their hearts.’ Boogaard is impressed by her students. ‘It amazes me how good they are at looking at themselves critically, and how they have the courage to do so. Especially at their young age.’

The concept “development” implies the assumption that Africa is backward

The course covers a number of African philosophers, and Boogaard sees herself primarily as a facilitator. ‘I grew up in a Western environment myself, with a Western education and culture. What I teach now is based on the input of African philosophers. That way, the students get an African perspective on African problems.’ Boogaard hopes the prize will lead to the course becoming a systematic part of the curriculum. ‘The fact that students appreciate this course so much, shows that it meets a need.’