WUR has the highest sickness absence rate of the four technical universities. Wageningen does not compare well with other universities either. A quest to find the causes reveals mental complaints as a key factor.

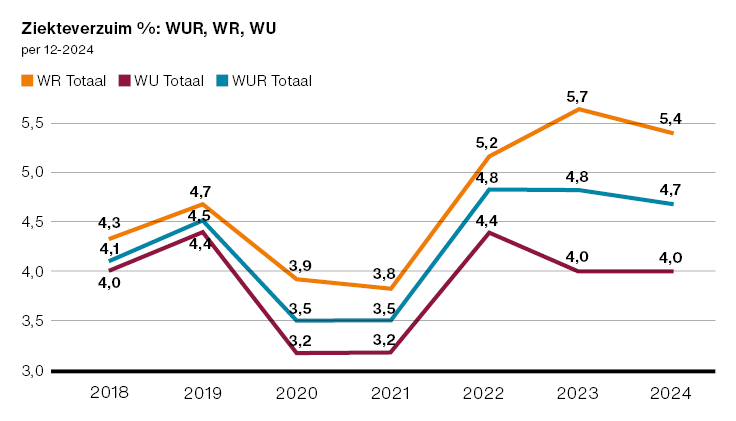

He calls it a ‘complicated issue’, one that puzzles him. Sickness absence at WUR is complex, says Human Resources director Martijn Scheen. The first thing you need to do when analysing it is to separate Wageningen University (WU) from Wageningen Research (WR). While they jointly make up WUR, their absence figures differ considerably (see inset below).

Strikingly, since the Covid pandemic, sickness absence has risen a lot at WR in particular. Other notable features, says Scheen – with Vitality & Health advisor Sander van der Nat and Vitality & Health team leader Dennis Kaldenberg at his side – are that ‘across WUR the health problems are often mental, and there are differences depending on age and sex.’ More on that later.

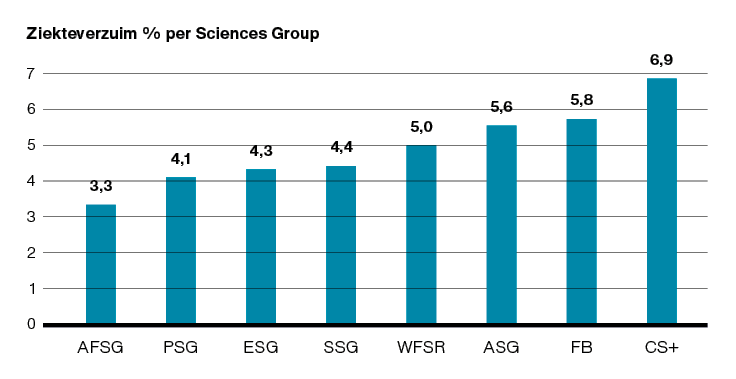

According to Kaldenberg, one reason for the increase in sick leave at WUR since the Covid pandemic is that sickness absence during the pandemic was unexpectedly low. ‘You might expect sick leave to increase during a pandemic but in fact it fell. That was probably because people were less likely to report sick. If you had a migraine during lockdown, you would still attend the online meetings and then you would have a lie down. Afterwards, you would carry on to make up the hours; you didn’t need to report sick. After the return to normal, we thought sickness absence would be back to about 4.5 per cent but it climbed higher and is now about 5 per cent for WUR and 5.6 per cent for WR, with a strikingly high figure for CS+ of nearly 7 per cent.’

Nuance

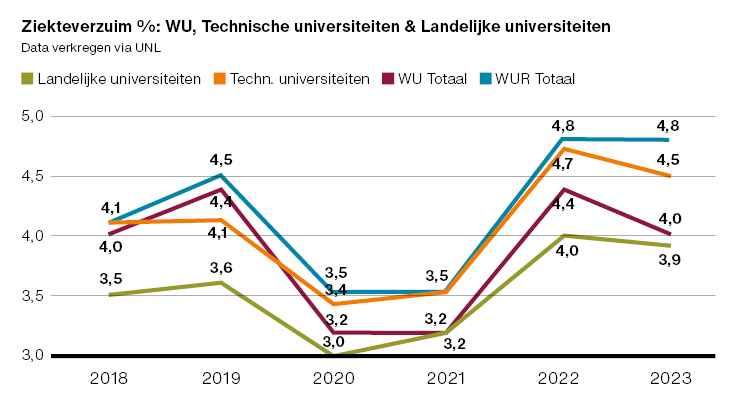

Kaldenberg says caution is needed in comparing the WUR figures against data for other universities (see inset) or the education sector in general. ‘WU has low sickness absence compared with other universities.’ According to Van der Nat, that is because the university has what he calls a lot of ‘room to make their own arrangements’. ‘Researchers have autonomy, which works well for enthusiastic staff. People in teams where they can make their own arrangements are less likely to report sick.’

Incidentally, the WU sick leave figures are not hard and fast, notes Kaldenberg: ‘We know there are science groups that don’t keep particularly accurate records. If someone reports sick with the flu after working 60 hours the previous week, they don’t record that day off sick with flu.’ So he’s saying that’s fine for the sickness absence rate, but it doesn’t give you realistic numbers. ‘That doesn’t mean the absence rate will be more than 4 per cent; it could equally be less.’ Kaldenberg mentions another point to take into account. ‘If you look at the national figures, WUR is about average; sickness absence in the third quarter of 2024 was 4.9 per cent. When you look at the national data for the education sector, WUR does very well, but that includes driving schools, which have extremely high absence rates.’

Those are the nuances. But without a doubt, the data contains some striking and concerning figures, concludes Scheen. One notable trend is the increasing absence due to mental health issues. ‘That has risen steeply in the past decade. It used to be a third of the total sickness absence, but now it has increased to 50 per cent. That’s a lot. Absence due to an unhealthy work-life balance has risen significantly, accounting for 36 per cent in 2024, the Occupational Social Work staff tell us. That’s up from 29 per cent in 2023.’

People who can make their own arrangements are less likely to report sick

While sickness absence due to work stress has fallen (from 36 per cent in 2023 to 18 per cent in 2024), Scheen says the two causes have to be seen in combination. ‘If you have problems at home, that affects your work. If a member of staff is pushing themselves hard at work and just about coping, an issue at home can be the final straw that leads to them reporting sick.’

PhD candidates

Another ‘very complicated issue’ (according to Scheen) that requires answers concerns the 25 to 35 age group, and particularly the women. ‘We’re seeing significantly higher sickness absence rates for that group across WUR.’ Van der Nat: ‘These are often young women with a family. Perhaps they have just bought a house with their partner, they have young children, they use up a lot of energy at home… but they also want to perform well at work. If the workload then increases, there is a big risk of sickness absence.’

The sickness absence figure for women aged 25 to 35 is significantly higher

PhD candidates are a specific risk group as well, explains Scheen. ‘They go straight from being a student to a four-year PhD position. They aren’t used to the rhythm of work yet. Their job requires a lot of self-discipline and the ability to deliver directly. If a PhD candidate becomes sick, that is a problem because they usually only have a contract for four years. That is a recipe for stress. Internationals often have a particularly difficult time. The Occupational Social Work people are often telling us we need to do more for them, such the young PhD candidates from Asia who might have had to leave young families behind to do their PhD here. We should also distinguish between the PhD candidates who are employed and the ones on a grant. WUR has a duty to be a “good employer” for the people in the first category, meaning they should get decent employee benefits and WUR should invest in their development, but we don’t have the same defined relationship with the people on a grant. We aren’t even allowed to give them any extras because that would break the tax rules, although we still do so sometimes. Last year, for example, we decided to give international PhD candidates on a scholarship with an income below the minimum some extra salary, even though the Dutch Tax Administration doesn’t officially allow this.’

Leadership

Another factor contributing to sickness absence is leadership, says Kaldenberg. ‘A lot of scientists at WUR have been promoted to managerial positions. A scientist is not necessarily a good manager. You get new responsibilities such as conducting sickness absence interviews. That requires very different skills. It’s a situation where poor leadership can lead to staff reporting sick or leaving. But the managers often stay in position because they are good scientists who can secure big projects. We’ve started helping managers with tasks like the sickness absence interviews.’

Finally, an increase in long-term sickness absence can be seen in the group aged over 55, says Van der Nat. ‘Older employees may have family care responsibilities, and the menopause can play a role with women. If something then happens at work, that may result in them taking sick leave. There is a task here for managers. You can’t simply “switch off” the family care tasks or menopause complaints, but measures can be taken at work to reduce the stress. For example, if people are already at the end of their tether, you can go easy on them in the stressful end-of-year rush.’

An employee who is off sick for two years can easily cost the organization 300,000 euros

The planned cuts of 80 million euros appear to be putting more pressure on the issue. After all, long-term sickness absence costs a lot of money. WUR is required to continue paying the salary; an employee who is off sick for two years can easily cost the organization 300,000 euros. Even so, Scheen says WUR has no intention of getting tough on sickness absence because of the cutbacks. ‘We are kind-hearted here in Wageningen. We would never put pressure on sick employees because of the cutbacks. And I’m proud of that. The Executive Board has however given me the go-ahead to take more action on combating long-term absence – an example being the appointment of Vitality & Health advisors like Sander. You should never use cuts or reorganizations as an excuse to sack someone who isn’t functioning properly or is on long-term sick leave. That is an important message, because cuts are generally not a good context for reducing sickness absence.’

Illustration Shutterstock

Illustration Shutterstock

“If someone reports sick with the flu after working 60 hours the previous week, they don’t record that day off sick with flu.’”

Maybe an example with a 60-hour work week hints at a bigger problem here??