There are several variables that can be measured to monitor fish health. Many such readings are taken outside of the fish. However, wouldn’t it be great to get a glimpse at what goes on inside of the fish? In its bloodstream, for example. Bram Kok, WUR’s very first EngD PhD student, developed a sensor that makes this possible. In theory.

Kok studied Physical Engineering in Twente. Towards the end of his master’s thesis, his supervisors suggested the EngD track in Wageningen to him. ‘They were looking for people to develop sensor technology. I thought that was cool. An EngD (Engineering Doctorate, Ed.) is comprised of one year of studying and one year of designing. That appealed to me.’

Next level

The project focuses on developing new sensors for research into aquatic organisms. Supervisor Arjan Palstra: ‘It is part of the NLAS innovation programme, which stands for Next Level of Animal Sciences. This programme was launched four years ago, and sensor technology is one of its domains.’

Palstra and his colleagues want to be able to continuously monitor the energy levels in aquatic organisms. ‘We want to know how they spend their energy and whether we can include this information in a digital twin for energy monitoring. Twente was working on a sensor to measure en interleukin-6, an immune marker for diseases. That fits in well with our model, which aims to include energy use, stress and health.’

That fits in well with our model, which aims to include energy use, stress and health

Arjan Palstra, Breeding and Genomics researcher

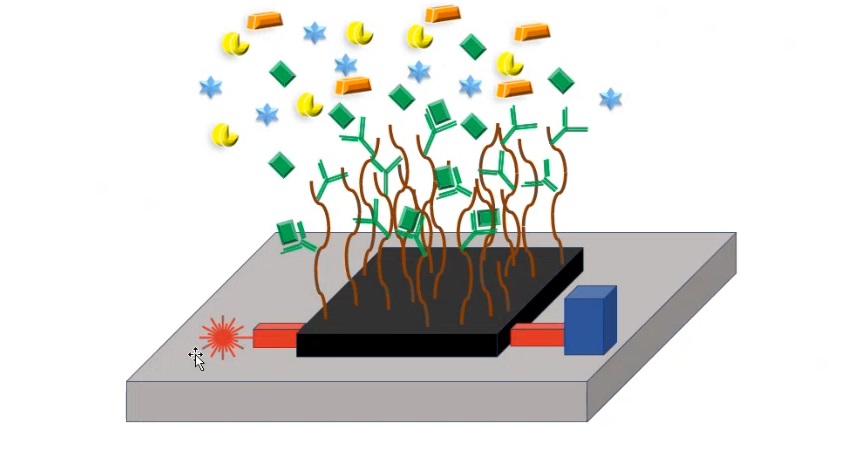

Kok developed a prototype detailing how such an internal biosensor might work. The essence is that the interleukin-6 protein in the bloodstream attaches to a thin layer of antibodies on the sensor. A tiny ray of incoming laser light is refracted, and that signal is sent to a detector. The amount of interleukin is an indicator of the fish’s health.

But that point has yet to be reached. Kok says, ‘The laser, the chip, and the detector are currently independent parts. ‘ ‘The idea is to have them fit on a sensor of about 1 square centimetre. Instead of blood, I used a buffer solution containing interleukin.’

‘Now that the design is available, we can implant it into the fish so that we can start taking readings in the bloodstream’, Palstra adds.

‘That means the sensor must be sufficiently sensitive. According to the literature, up to 0.2 nanograms per millilitre are biologically relevant concentrations’, Kok says. ‘These concentrations can go up to 0.8 nanograms when fish are ill, which is what we can currently just measure. We are getting close. I believe the accuracy can be improved, but my time as an EngD has come to an end.’

Humans

For practical reasons, Kok used human interleukin instead of interleukin of fish. Fish interleukin is difficult to come by, while the human kind is, in a manner of speaking, fully stocked. ‘But that only serves to make it more interesting’, Palstra states. ‘It may now lead to a sensor capable of measuring humans as well.’

Moreover, the method is not restricted to interleukin. Kok: ‘It can easily be adapted to other biomarkers. Stress or reproduction hormones in the bloodstream can be measured with other biomarkers. This type of optical diagnostics is booming and leads to devices that bring health care closer to the people without the need for a laboratory.

Bram Kok is the first researcher to successfully complete the EngD programme at WUR. The milestone is to take place on Thursday, 13 February, in Omnia. The ceremony will be largely similar to that of a normal PhD defence. ‘I will have three opponents: one from within WUR, one external and someone from my supervision team. Instead of a dissertation and propositions, I have my design and an extensive report.’

Photo Shutterstock

Photo Shutterstock