He came to tell a story, really. ‘But today I have also heard enough new stories to fill at least six months’ worth of radio programmes.’ So said the well-known British food journalist Dan Saladino, who was in Wageningen at the invitation of Liesje Mommer and Marleen Riemens, coordinators of the WUR-wide research programme Biodiversity-Positive Food Systems (B+FS).

Saladino was in Wageningen for the closing conference of the programme. He, Mommer and Riemens share a major concern: the incredibly fast decline in biodiversity, which is driven to a significant extent by the global food system. Saladino wrote a book about it: Eating to Extinction. During his presentation on the subject, the attendees hung on his every word: Saladino is a born storyteller.

An apple a day

Saladino kicked off by sketching how his interest in this topic was awakened. While preparing for his BBC radio programme, he stumbled upon Ark of Taste, an international list of threatened culinary heritage drawn up by the Slow Food movement. ‘I discovered that in Victorian England, you could eat a different apple every day for four years. That level of variety is in stark contrast with what the British supermarkets have to offer nowadays. I wanted to get to the bottom of why that happened, how it happened – and whether we should be worried about it.’

His curiosity led to years of exploring the global food system and its history. In Omnia he talked, for example, about the ‘wheat man’ Arthur Ernest Watkins, a contemporary of Vavilov, about whom ex-WUR President Louise Fresco wrote the novel The Plant Hunter from Leningrad. Watkins studied in Cambridge, but was sent to France shortly after the outbreak of the First World War to scout for possible food supplies for the British troops. He was struck by the vast range of wheat varieties in France. When he returned to Cambridge after the war and got to know the work of William Bateson, the ‘father of modern genetics’, he approached his contacts in France and parts of what was then the British empire so as to collect as many different grain varieties as he could.

Watkins Wheat Collection

This resulted in what is now known as the Watkins Wheat Collection, with 827 different grain varieties from 32 countries. Recently, British and Chinese scientists have sequenced the DNA of every variety, thus opening up a ‘genetic goldmine’, as The Guardian called it. Among the researchers’ finds in the collection were 33 still unknown species of wheat that are resistant to a devastating fungal disease, and species that can grow in salinized soils. ‘In a time when the world has more and more mouths to feed, and growing conditions in many places are becoming increasingly difficult, these are crucial finds,’ says Saladino.

He thinks this story is indicative of how incredibly precarious agro-biodiversity is. ‘We have that single individual to thank for the fact that the world can now fall back on those old, robust wheat varieties. Without Watkins, the heritage of 10,000 years of agriculture by our forefathers could just have been lost.’ In that context, Saladino also points to Cary Fowler, the founding father of the famed Svalbard Global Seed Vault in Spitsbergen. Since 2008, a collection of the seeds of nearly 1.2 million plant species have been stored under the permafrost to prevent them being lost to climate disasters, plant diseases or wars.

Planetary boundaries

Saladino also paid attention to the dramatic effects of the modern food system. ‘Humanity has already crossed six of the nine planetary boundaries. And food is largely to blame for that.’ He gives a few examples: ‘Our food system is the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases: between 25 and 30 per cent worldwide. It is also the biggest cause of biodiversity loss. The fact that we are now talking about the sixth mass extinction of species is partly due to the sacrificing of rainforest and wetlands to agriculture or grasslands.

Humanity has already crossed six of the nine planetary boundaries. And food is largely to blame for that

The food system is also the biggest user of fresh water: 70 per cent of all the fresh water in rivers, groundwater and lakes is used for irrigation. And then there is the massive impact of excess nitrogen and phosphorus, or the overdosing of pesticides, insecticides and herbicides – the list goes on.’

Health threat

This reality is depressing, but it does offer an opportunity, emphasizes Saladino. ‘As Johan Rockström (the scientist who coined the concept of planetary boundaries, ed.) says: the planet is starting to send us bills. The food system not only harms the planet but is now the biggest threat to human health. Every year, 10 to 11 million people die too young because of unhealthy food: globally, diseases such as obesity and type 2 diabetes are rising fast. With far-reaching consequences.’

We’ve ended up in a food system that we have to combat with drugs

He illustrates this with the recent announcement by the British government that it plans to pump 300 million pounds into a project with the pharmaceutical industry aimed at combatting obesity with new drugs such as Ozempic. Obesity already costs the British healthcare system more than 11 billion pounds a year. ‘So we have ended up with a food system that we have to combat with drugs for the sake of our health. That suggests that we urgently need to repair our food system. If we manage than, we also have a chance of repairing the planet!’

Soup

The million-dollar question is, of course, how? Saladino described some examples of international practice that resemble projects implemented by researchers from the B+FS programme and the related CropMix programme: strip farming, specific crop combinations, combined cropping and ‘intercropping’. Saladino is a particular fan of the latter. He gives an example in which crops such as lentils, grass peas, fava beans and rye are sown as a mix in one field and are all harvested at the same time. ‘There’s a reason for this: they form a single meal together, a soup. So they belong together – both in the field and at the table. They are a unit, culturally and nutritionally.’

According to Saladino, this is an important concept to grasp. ‘There’s a reason that people have always “eaten the landscape”.’ Intercropping is based on the way different plants cooperate in the interests of soil quality and resistance to pests and diseases. And it works. So in spite of all the alarm bells that are ringing, I’m optimistic about the future, not least because nobody wants a scenario in which governments are dependent on big pharma to protect people against the food the system serves them up. We urgently need to invest in a food system that is good for the planet and for us. And I think biodiversity forms the heart of that.’

Deliberately ‘eating to extinction’

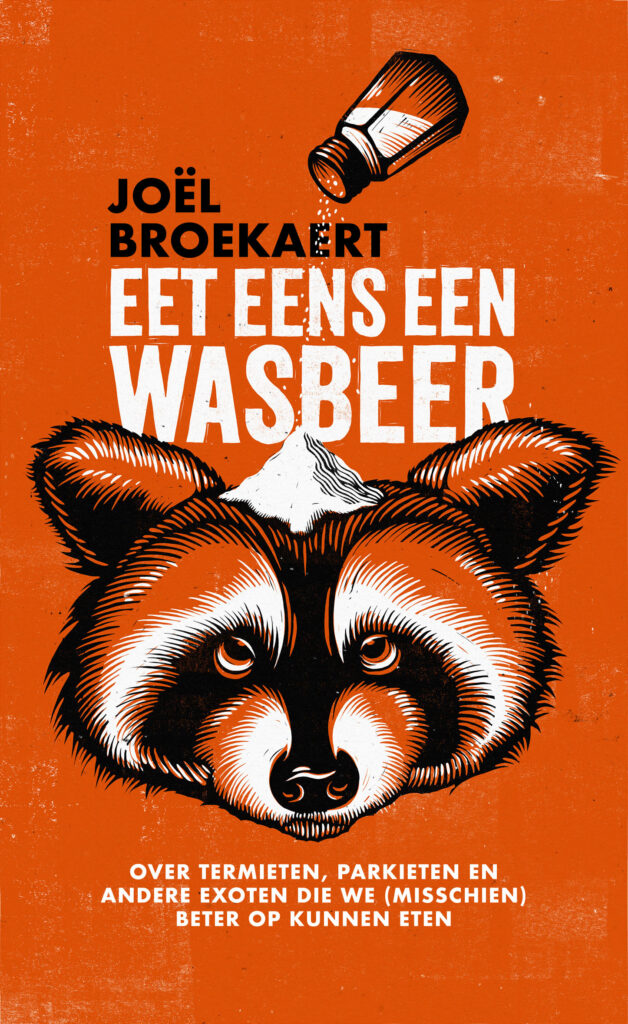

Last month, the Dutch culinary journalist Joël Broekaert published a book exploring the option of deliberately eating ‘to extinction’ in the interests of biodiversity. His book Eet eens een wasbeer (Eat a raccoon) is about invasive exotic species such as the Egyptian goose and the Japanese oyster. ‘We kill these animals and just throw them out while at the same time we raise animals in unsustainable numbers and often under horrific conditions to supply ourselves with meat,’ says Broekaert. What if we put these exotic species on the menu? Is that possible, and is it even allowed? And are they at all tasty? He explores these questions in his book, for which he consulted experts including WUR researchers such as shellfish expert Karin Troost (Wageningen Marine Research) and crayfish experts Ivo Roessink and Fabrice Ottburg (Wageningen Environmental Research).

Maroon rice

A study of Maroon rice by the Biosystems chair group fits seamlessly in Saladino’s narrative. The term refers to varieties grown in the interior of Suriname by the Maroons: descendants of Africans who fled slavery. The 136 varieties of rice being studied turn out not just to be of historical interest (reflecting colonial history) but also relevant to the future. The global rice market is dominated by a handful of varieties, all of which flourish under highly specific conditions. The Maroon varieties can cope with a wider range of climatic and ecological conditions, and without pesticides and artificial fertilizers. Nature recently published a new article about this study.

The essential 17

Three quarters of our food comes from just 17 species of plants and animals. That alarming fact was shared on LinkedIn recently by Wageningen Livestock Research. In that post, Sipke Joost Hiemstra, director of the Dutch Centre for Genetic Resources (CGN: one of WUR’s statutory tasks) explained: ‘Breeding has drastically increased the production value of species, but it has also gradually made agriculture more homogeneous, with species that produce bigger yields, but that require a lot more “pampering”. That brings risks with it. We can see a similar trend in livestock farming. We must look for a bigger variety of breeds in order to make our farming systems more resilient. The CGN’s huge collection of genetic resources will play a key role in this quest.’

British food journalist Dan Saladino during the closing conference. Photo Guy Ackermans

British food journalist Dan Saladino during the closing conference. Photo Guy Ackermans