Well, obviously not with Charles Darwin, the founding father of the theory of evolution. Charles Darwin arrived at the Galapagos Islands on the ship The Beagle in autumn 1835. Lozano visited the same place as part of Darwin200 expedition, and spent three days there with Charles Darwin’s great-great-granddaughter Sarah Darwin.

As a scientist, you can’t get closer to Darwin than that, admits Lozano. ‘It was an amazing experience. We went to search for the endemic tomatoes together. She did her PhD at University College London on the systematics and genetics of tomatoes on the Galapagos Islands That was handy as she had no trouble identifying the plants.’

Tomatoes

Like Sarah Darwin, Lozano studies tomatoes. Or to be more precise, he studies how nematodes infect the roots of tomato plants and make use of them. After the infection, the nematodes transform the host into what is termed a feeding cell. This cluster of cells feeds the worm. Lozano is trying to figure out exactly how the worm does that.

‘I am also looking at the evolution of these feeding cells,’ he explains. ‘In the course of evolution, nematodes have developed the capacity to eat plants through feeding cells four times. There are nematodes that create very primitive feeding cells from a handful of plant cells, but others are able to combine up to 500 cells to make one large feeding cell. I try to understand this development.’

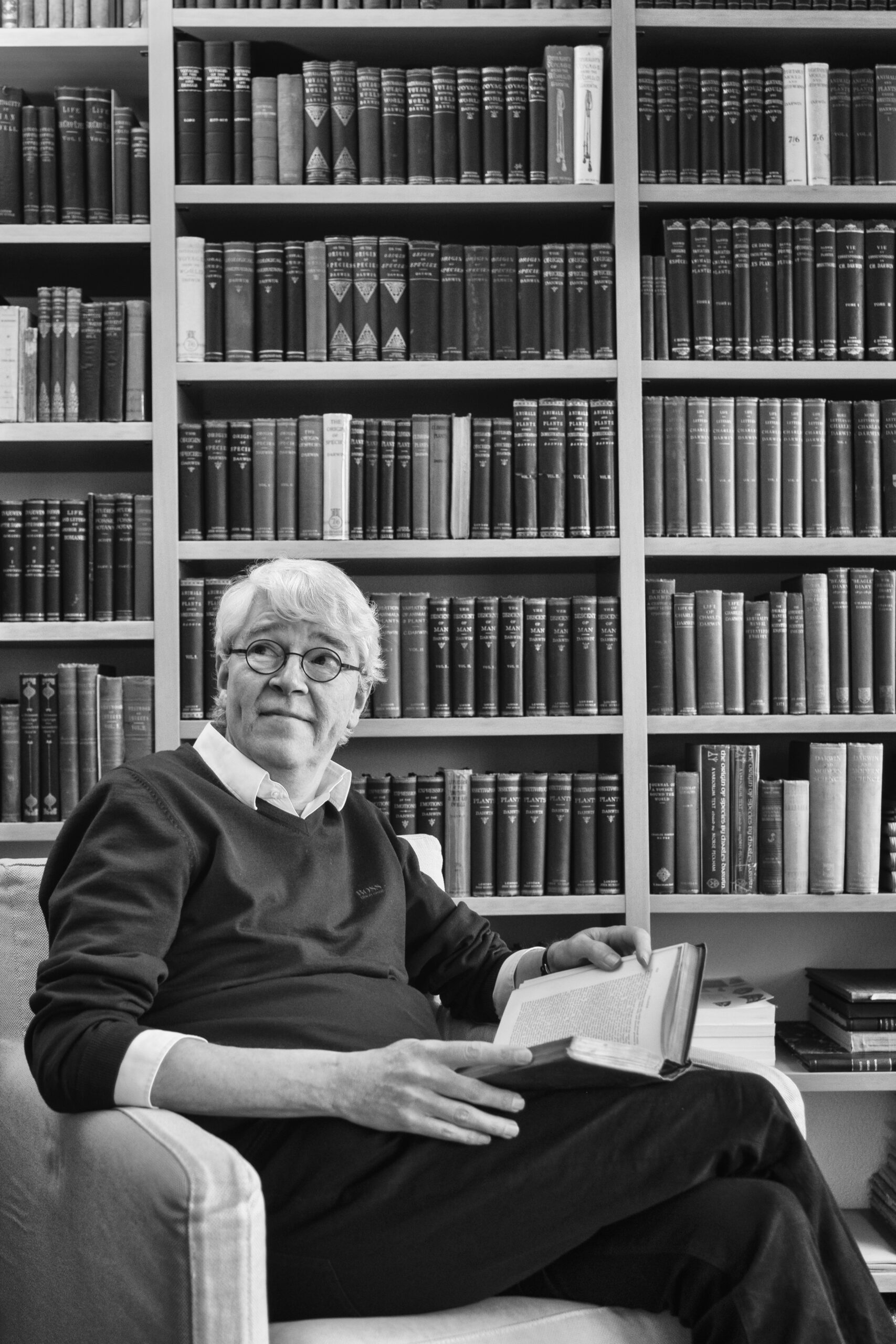

When Lozano was asked whether he wanted to look for old tomato plants on the Galapagos Islands, he didn’t hesitate for a moment. ‘Fantastic. The chance to do research there is the dream of every biologist and plant scientist.’ The invitation came from Pieter van ’t Hof, a WUR alumnus and now a professor at San Francisco de Quito University in Ecuador. ‘I met him in Switzerland when I was doing my PhD research. We were both studying the same type of proteins at the time.’

Soil

Research on the Galapagos Islands usually focuses on the unusual birds and other animals on the islands. ‘No one looks at the microbiome in the soil,’ says Lozano. But that is precisely what this part of the Darwin200 expedition does do, almost 200 years after Darwin himself reached the islands. ‘There are some very unusual micro-organisms in the soil that can tolerate drought, salinity and heat. Those happen to be some of the biggest problems we are now having to tackle.’

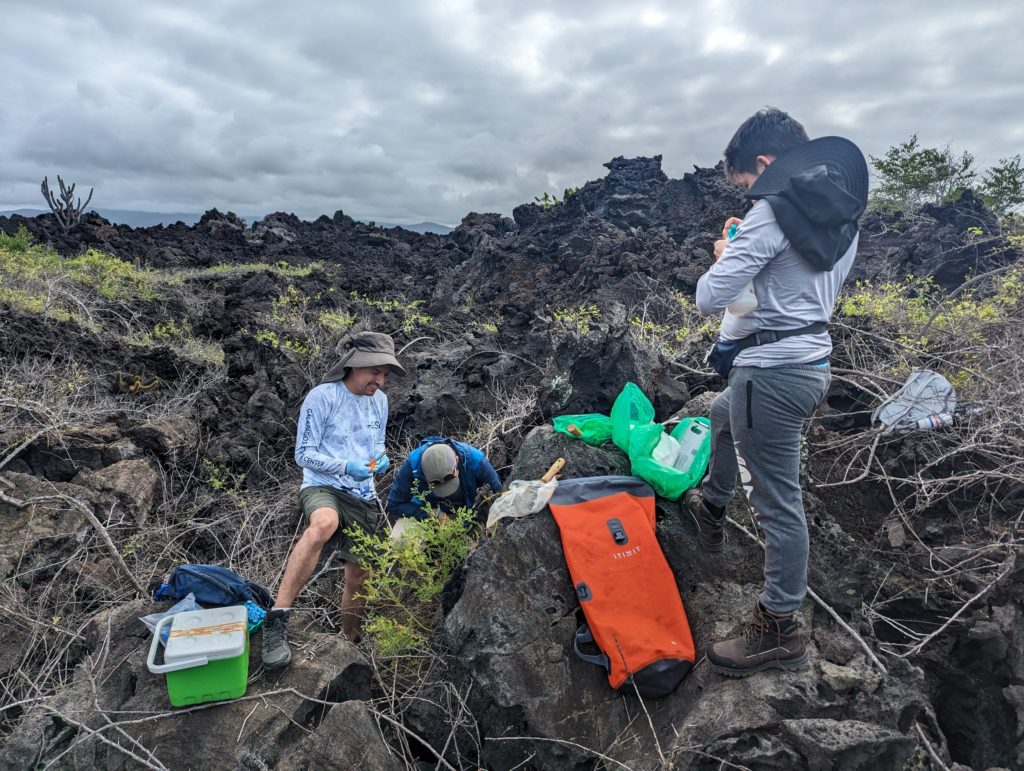

Lozano, and the team he was part of, studied the microbiome of tomatoes. They took soil samples from the four tomato varieties found on the various islands. Two are endemic, while the other two were introduced over the course of time. Lozano: ‘We look at the differences in the microbiome between the endemic species, the introduced tomatoes and the ones found in continental Ecuador.’

Volcanic

The key question is why the endemic species do so well in the place where they are found. ‘It is an incredible sight,’ says Lozano enthusiastically. ‘They grow in volcanic soil, which has nothing else apart from a few cactuses. That is unique and extraordinary. The conditions are so dry and yet they do well. How come? Which micro-organisms are important?’

The lab work is carried out in Quito by a WUR alumnus and former student of Lozano’s. ‘Iwan Astudillo Estévez, an Ecuadorian who is now doing a PhD with Van ’t Hof as his supervisor.’ And to add to the Wageningen flavour: the head of the Darwin200 tomato project is alumnus Hanna Hogenboom.

Jose Lozano (right) with Pieter van ‘t Hof, Sarah Darwin en Iwan Astudillo Estévez. Selfie Jose Lozano

Jose Lozano (right) with Pieter van ‘t Hof, Sarah Darwin en Iwan Astudillo Estévez. Selfie Jose Lozano